(Prepared within KHAR Center’s Azerbaijan Authoritarianism Research Series)

✍️ Elman Fattah – Director of KHAR Center

Introduction

Azerbaijan’s political system may appear strange—and at times deceptive—to external observers. Officially, the country has numerous “political parties.” Presidential, parliamentary, and municipal elections are held regularly. State television and several private channels broadcast programs labeled as “political debates.” Government representatives repeatedly emphasize that political pluralism exists in Azerbaijan.

For an observer who does not investigate the deeper structures of daily political processes, this argument may seem somewhat convincing: there is an “opposition,” elections are held, and media operates. It simply appears that the “people’s” choice is consistently in favor of the ruling power.

In reality, however, the weakness of the opposition is neither an accident of fate, nor merely the outcome of certain leaders’ personalities, nor a product of society’s supposed “fatigue with politics.” The weakness of the opposition is a structural phenomenon created through a deliberately designed and continuously updated system built upon legal, institutional, economic, and informational resources controlled by the state apparatus.

The political environment has been shaped in such a way that not only is it impossible for a genuine opposition to become a center of power—it is nearly impossible for it to exist at all. The electoral system is regulated so that competition appears to exist, but outcomes are predetermined. Party and NGO legislation allows only for satellite activity. The media environment is under such total control that the term “opposition” is perceived as a threat within broad segments of society.

The main purpose of this article is to examine the structures that produce the artificial weakness of the opposition. The goal is not to discuss isolated incidents, individual arrests, or events surrounding particular leaders, but to reveal how the system functions as a whole. In this regard, the central questions we focus on are the following:

- Does the opposition’s weakness stem only from internal organizational issues, or is it the outcome of structural constraints deliberately designed by the regime?

- Where does this weakness originate, and through which stages has it evolved to reach its current state?

- How did the process unfold from the chaotic pluralism of the 1990s to the “managed stability” of the 2000s, and further to the current stage of “victory legitimacy”?

- Through which mechanisms does the government create artificial weakness?

The text strives, on one hand, to be written in a clear and accessible language suitable for a wide audience. On the other hand, it aims to preserve analytical depth and employ the conceptual frameworks provided by political science and authoritarianism research.

The purpose of this analysis is not to engage in debates about “who is right and who is wrong,” to judge individuals, or to offer an “ideal model of opposition.” Rather, it seeks to explain—structurally—how Azerbaijan’s political system gradually marginalizes the opposition. Put another way, this study attempts to reveal not the symptoms of the illness, but its anatomy.

The following sections of the text will examine, stage by stage, the brief history of Azerbaijani authoritarianism, its legal and institutional structures, the mechanisms of information warfare, the opposition’s internal weaknesses as well as the dependencies created by the system, and finally the place of this model within the broader regional context. The goal is for the reader to understand the question “Why is the opposition weak?” not through the lens of “public apathy,” but through the perspective of the political system as a whole and the long-term strategic choices that have shaped it.

Theoretical Framework

Throughout history, authoritarian political systems have been distinguished by two main governance models. The first model represents a regime of total prohibition and totalitarian control; in this case, political competition is fundamentally eliminated, and all independent institutions either cease to function or operate under full control. The second model relies on a strategy of partial competition and managed pluralism: pluralism exists formally, but competition is adjusted to align with the interests of the government, and outcomes are predetermined (Barbara Geddes, 1999).

Since the mid-1990s, Azerbaijan gradually moved toward the second model. There were several reasons for this:

- In order to establish normal relations with the West, it was necessary to tolerate the formal existence of democratic institutions.

- Society was politically more active.

- Eliminating competition entirely would damage legitimacy.

- Oil revenues initially dictated a softer authoritarian structure.

Political scientist Andreas Schedler characterizes such systems as regimes operating according to the principle of “there are elections, but no choice.” According to what he calls the “menu of manipulation,” an authoritarian regime employs the following methods to ensure its continuity:

- it does not entirely ban competition, it merely keeps it under control;

- it sets the boundaries of political activity itself;

- it keeps the activities of opponents within a “safe zone” (Andreas Schedler, 2002).

Gandhi and Przeworski emphasize that some authoritarian regimes are not interested in completely destroying the opposition. In their view, the most suitable opposition for authoritarian leaders is one that remains visible in the political arena but is unable to influence outcomes. This creates a sense of competition while indirectly supporting the legitimacy of the system (Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski, 2006).

The Uniqueness of the Azerbaijani Model

The Azerbaijani model stands at the intersection of these theoretical approaches. However, two key features distinguish it from others:

- Victory legitimacy – After 2020, the government presents itself as the “force that restored historical justice.” This is an exceptionally powerful source of legitimacy, rarely seen in the region.

- Energy – Oil and gas revenues, together with mechanisms of economic co-optation, help reduce public discontent by ensuring a certain level of social welfare (Elman Fattah, November 2025a).

Thus, Azerbaijani authoritarianism is neither identical to Kazakhstan’s institutional model, nor Belarus’s repressive model, nor Russia’s ideological authoritarianism. Azerbaijan’s political system represents a unique authoritarian mutation with its own characteristics.

The System Is Built, Opponents Are Eliminated

With Heydar Aliyev’s return to power in 1993, the ideological and institutional foundations of the authoritarian system were established (Kharcenter, May 2025a). This architecture was constructed in such a way that the opposition could not pose a serious threat to the system. At the time, the Popular Front Party of Azerbaijan, Musavat, and other democratic political forces were portrayed—even in official state statements—as threats. Over time, their activities were framed within categories increasingly associated with criminal behavior. Party leaders and activists were regularly arrested. Regional organizations collapsed, and sources supporting the opposition were destroyed. Rallies and demonstrations were consistently dispersed, and organizers were punished (RFE/RL, 2003).

This period was also crucial for the future of the media. The relative pluralism achieved in the early years of independence began to fade. State television became completely controlled by the government, and political content on private channels was strictly filtered. The financial situation, advertising revenue, and business operations of the print media were significantly affected by the authorities. At the same time, the government circulated the narrative that “the opposition brings chaos” (Kharcenter, May 2025b).

To firmly anchor this political accusation in public consciousness, the discourse was repeated regularly. The economic hardships of the 1990s, the Karabakh war, and attempted coups remained vivid in public memory, enabling the government to present the opposition as the “enemy of stability,” referencing these collective traumas (Elman Fattah, November 2025b). In doing so, the government created widespread fear of political change within society.

Thus, the period from 1993 to 2003 is characterized not only by political restrictions but also by the foundational construction of the opposition’s artificial weakening.

Legal and Institutional Engineering

After 2003, the authoritarian system entered a new phase. While repressions continued, the main focus shifted toward restructuring institutional and legal frameworks. The defining feature of this period can be summarized as follows: competition should exist, but without influencing outcomes. To this end, several significant steps were taken:

- The Election Code was rewritten;

- The mechanisms of competitive elections remained only on paper, while practical opportunities were restricted;

- The composition of election commissions at all levels was fully brought under control;

- All stages of the electoral process were aligned with the appearance of legitimacy. The procedure for reviewing election complaints became purely formal. That is, complaints were reviewed—but rejected (Trend, 2008).

During this period, the internal informational environment came under full control. Simultaneously, the independent NGO sector that supported the opposition was deliberately weakened, and the work of international organizations was restricted. These measures reduced the opposition’s capacity for public outreach, civic education, and organizational development.

Meanwhile, the ruling New Azerbaijan Party became intertwined with state structures. Almost everyone employed in state-funded institutions was made a member of YAP. Consequently, resources and decisions were shaped within a party-state mechanism. Parliamentary representation for principled opposition parties was eliminated starting from 2010. Thus, by 2003–2013, the process of pushing the opposition out of the system was completed (OSCE/ODIHR, 2010). The opposition existed, but it had no influence. Parties were active, but could not transform into real power. Formal political competition existed, but did not affect outcomes.

This phase established the institutional architecture of the opposition’s artificial weakness.

The Era of Online Control — The Regime’s New Weapon: Information

From 2013 onward, Azerbaijan’s political system entered a completely new era: the era of the internet and social media. This innovation created difficulties for the government, but also provided it with a new instrument of control. During this phase, the government implemented several strategic approaches.

Troll networks operated continuously, targeting opposition leaders, damaging their reputations, and shaping public political perceptions on digital platforms. As a result, a manufactured image of “mass support” for the government emerged.

The activities of the security services focused on disseminating kompromat and deliberately steering public discussions in a negative direction (HRVV, 2016). During this period, the intellectual segment of the opposition and young activists became key targets. They were either arrested or forced into exile due to persecution.

This situation dealt a serious blow to one of the opposition’s most valuable resources: the production of alternative ideas.

Depoliticization of Society

The “victory” created short-term mobilization in society but also led to long-term depoliticization. The narrative that “there is no need for an opposition after the war” became more systematic. Politics was pushed out of everyday life, and social apathy deepened. During this period, the artificial weakening of the opposition reached its maximum level.

Formalizing Weakness

The artificial weakening of the opposition within the political system is not achieved solely through repression or damage to reputation via the media. One of the key factors ensuring the durability of an authoritarian regime is legal and institutional engineering. In other words, the laws formally demonstrate the existence of pluralism, but they are designed in such a way that everything remains only on paper. Put differently, the Azerbaijani model is built on a structure that effectively enforces the “rule of the regime.”

The Law on Political Parties (2022): A Program for the Institutional Elimination of the Opposition

The new Law “On Political Parties,” which represents a significant turning point in Azerbaijan’s political system, was presented under the pretext of “creating a systematic party environment,” but in reality it prevents independent political organization.

For example, the requirement of 5,000 members for party registration is unprecedentedly high even by post-Soviet standards. This creates substantial obstacles to independent organizing and makes the registration of parties outside government control effectively impossible.

In addition, state registration acts as a political “sword.” Any minor “inconsistency” in documentation may serve as grounds for liquidation. At any time, the government may demand a new inspection or “verification of membership data,” resulting in a party’s removal from the system (E-qanun, 2022). Another aspect is that since members’ names are recorded and monitored by state bodies, they become potential objects of pressure. The primary purpose of this mechanism is to expose the opposition to constant legal danger.

Thus, Azerbaijan’s legal and institutional architecture does not accidentally produce the weakness of the opposition. Through this engineering, the regime both defines the boundaries of competition and ensures their enforcement. Consequently, the 2022 law effectively pushed the opposition out of the system. While competition was merely restricted in 2003–2013, this law eliminated competition institutionally.

Economic Pressure and Social Control

The regime knows very well that the opposition’s main pillar is neither social media nor foreign assistance. The most valuable resource for the opposition is people and their capabilities—that is, activists’ ability to work, live, provide for their families, fund their organizations, and sustain their activities through material and economic independence. Authoritarian systems understand this perfectly, and therefore use suffocating economic tools as the most effective method for neutralizing the opposition. Since the 2000s, the Azerbaijani government has consistently acted in this direction.

It is important to note that economic pressure is not aimed solely at making the lives of certain individuals difficult—it serves a broader systemic purpose. This policy is the most effective method for structurally weakening the opposition.

Most opposition members in Azerbaijan have been unemployed for long periods. Their chances of working in the state sector or private companies are limited. Even working as an ordinary teacher, doctor, or engineer is considered a “political risk” (MEYDAN.TV, 2024). This policy serves four main purposes:

- To make people’s everyday lives difficult;

- To turn political activity into a profession that brings no income;

- To present opposition involvement as a “source of problems” within families and social circles;

- To prevent new people from joining the opposition movement.

Thus, being an opposition member in Azerbaijan means becoming a target of family and social disapproval.

Moreover, one of the distinctive features of Azerbaijan’s authoritarian system is that punishment is applied not only to “the political activist himself,” but also to his family members and close relatives (HRVV, 2017). This approach turns political activism into a profession with severe consequences. Such pressure is especially effective because it targets one of people’s deepest vulnerabilities: family responsibility. This substantially reduces the opposition’s social base.

These economic pressures artificially weaken the Azerbaijani opposition and serve as a strategic pillar protecting the security of the authoritarian system.

Discourse engineering

Authoritarian systems do not content themselves with applying only police, court, law, and economic pressure against their opponents.

Their most effective weapon is control over thought.

This includes the discourses that shape how society understands politics and which values it considers legitimate and which ones it considers dangerous.

Since the 2000s, the leadership of Azerbaijan has built an information architecture on the basis of several important stories.

These portray political activity, in a psychological sense, as unnecessary, meaningless, and even dangerous.

The main purpose of such narratives is, alongside weakening the opposition, to distance the entire public sphere from politics.

In this context, three main strategic stories come to the forefront:

“The opposition is weak and the people do not want them.”

(Acceptance of artificial weakness as natural.)

The purpose of this narrative is not to explain the real weakness of the opposition, but to ensure that the artificial weakness created by the government is accepted by society as “normal.”

This message has been repeated in different forms for 30 years:

- “No one supports them,”

- “1,000 people attended the rally,”

- “Society does not believe the opposition,”

- “In the eyes of the people they are not an alternative” (Modern.az, 2013).

Such expressions create two main effects in people’s thinking:

a) The hope for political change is eliminated.

If the idea “the opposition is weak” is regularly instilled in society, then people see no chance for political change.

The loss of hope makes politics into a meaningless activity.

b) The artificial weakening created by the regime is presented as “objective reality.”

People do not notice economic difficulties, legal barriers, and repressions; as if the opposition is weak because of its own incompetence.

“The opposition serves foreign forces.”

(Delegitimization and rendering dangerous strategy.)

This is one of the most fundamental and effective styles of the regime.

The purpose is to present the opposition as a “threat” in terms of national identity, the state, security, and sovereignty (sesqazeti, 2015).

There are three main accusations in the structure of this narrative:

a) The opposition acts according to “Western instructions.”

This message easily finds place in societies with suspicions toward the West.

b) The opposition is presented as “against the state.”

This accusation appeared in a more targeted way particularly since 2020.

Society’s emotional reactions related to the Karabakh issue create favorable conditions for this manipulation.

c) The opposition “aims to disrupt stability.”

This is a security-centered discourse widely used in authoritarian regimes:

“If we are not here, the country will collapse.”

The goal behind these accusations is to show the opposition not as a political rival, but as a psychologically “dangerous category.”

Thus, political debate is built not on ideas, but on fear of security.

“After the Patriotic War, unity is necessary.”

After the 2020 war, a significant change happened in the discourse implemented by the government.

The regime began presenting itself as the holder of a national mission that restored historical justice (Elman Fattah, November 2025d).

This discourse operates at three different levels:

a) “There is no division in the period of victory.”

Here, the word “unity” in fact means “to gather under the umbrella of the government.”

Political criticism and alternative ideas are presented as “harmful for the nation.”

Any criticism from the opposition is interpreted as casting a shadow over the victory.

Any political protest is evaluated as an “unpatriotic action.”

This narrative is extremely important for the system because:

- the opposition appears not only weak and dangerous, but also unnecessary;

- the political system is romanticized as a “government that has fulfilled its historical mission.”

Thus, the artificial weakening of the opposition is reproduced not only by legal and institutional mechanisms, but also by engineering the information environment.

Internal weaknesses of the opposition

This section does not target any political organization or leader.

The points here are structural analysis: meaning the internal difficulties of the opposition derive not only from personal incompetence, but largely from objective results of long-term pressure and restrictions created by the system.

Authoritarian regimes prevent the opposition from strengthening not only by repression, court measures, economic pressure, and media manipulation, but also by intervening in the opposition’s internal environment.

This leads to the formation of “structural weaknesses” accumulated over years.

These weaknesses include not only the opposition but also society.

They are the product of the design of the political system.

In this context, three main structural weaknesses become visible:

Leadership vacuum

The Azerbaijani opposition still carries the traces of the systematic leadership repression from 1993–2013.

In the past 15 years, young political leaders were removed through imprisonment; locally known activists were neutralized either by courts or dismissal from work (HRVV, 2013).

Presenting politics to youth as a risky, dangerous, and hopeless activity stopped the continuous process of cadre formation in the opposition.

As a result, succession and the mechanisms for passing down experience, which are necessary for producing new leaders, were lost.

Thus the opposition aged not only in leadership structure but also in membership, turning into dissident clubs.

Brain drain

Over the last fifteen years, thousands of activists, journalists, scholars, civil society members, young specialists, and independent experts have left the country.

This is not simply personal choice; it is the result of the pressure environment created by the system (HRVV, 2024).

During this process, opposition parties lost:

- their intellectual base,

- the group of specialists who prepared political strategies,

- the analytical environment that developed conceptual thinking,

- creative and experienced personnel in the NGO sector.

Social apathy

Since 2014 — the year after Ilham Aliyev’s third presidential election — Azerbaijani society has entered a deep depoliticization process.

This has three main reasons:

a) Politics is regarded as a risky activity.

When people see dozens of examples of people imprisoned, losing their jobs, or being forced to migrate due to political involvement, they begin to distance themselves from politics.

b) In an environment without competition, politics loses meaning.

If people think “the result does not change,” then they stop participating.

Leadership vacuum, brain drain, apathy, and systematic depoliticization have weakened the broad base of the opposition.

This makes it possible to see the objective cause of the opposition’s weakness in the structures created by the regime.

“Parallel opposition”

One of the important features of Azerbaijani authoritarianism is the existence of fake opposition organizations that it builds and controls.

The goal of this approach is to create the appearance of false pluralism that replaces real competition and does not cause any change in political outcomes.

Although this phenomenon appears in various forms across the post-Soviet space, the Azerbaijani model differs from others in size, systematic nature, and functional impact (Jamil Hasanli, 2013).

Why does the regime create fake opposition?

Authoritarian regimes avoid openly saying “there is no competition here.”

They preserve the appearance of competition but control its main features.

The opposition parties formed by the system act only as symbolic rivals in elections.

They take part in political discussions and operate in parliament with the status of opposition.

This decoration is important because it sends the message to society and abroad:

“Our competitive field is active, but the opposition is weak.”

Another reason for forming fake opposition is to present the real opposition as an “external” element.

Different approaches are used for this:

a) Describing the real opposition as radical.

Fake opposition is presented as “smart,” “civil,” and “constructive,” while the real opposition is described as “radical” and “anti-state” (Sofie Bedford and Laurent Vinatier, 2018).

b) Misrepresentation of media balance.

To create the appearance of “balanced broadcasting,” fake opposition is given ample airtime on television.

c) Performing the role of “alternative” in parliament.

This opposition, empty at its core, expresses only cosmetic objections and never presents views that could seriously harm the system.

This weakens the legitimacy of the real opposition in society.

d) Sending a message to international partners:

“We have a multi-party system; we provide the image you require.”

Organizations such as the Council of Europe, OSCE, and European Parliament pay attention to the formal side of democracy.

The regime knows this.

This is an effective way to reduce pressure from the West.

Thus, fake opposition serves not only to weaken the principled opposition, but also to strengthen the government’s legitimacy abroad.

Post-opposition period

The 2020 war fundamentally changed Azerbaijan’s political system.

The new power and political capital that victory created for the government led to political activity being measured through loyalty to statehood, but in reality loyalty to authoritarianism.

The environment for opposition activity sharply narrowed: now one must either be “pro-state/pro-Aliyev” or carry an “anti-national” image.

Those outside the framework set by the government were labeled “pro-Armenian,” “supporters of chaos,” Russian agents, and “tools of the West” (Elman Fattah, November 2025c).

The legitimacy obtained through the war became the main criterion for evaluating political relations.

Gradually, the concept of opposition began to disappear from political rhetoric and was replaced with a model of “permitted criticism” that allows positioning only within the system.

Thus, the main feature of the newly formed post-opposition period is that the existence of real alternative subjects in the political arena is no longer regarded by the system as either a threat or a dialogue counterpart.

Opposition as a political institution is now considered unnecessary (Elman Fattah, Nov 2025).

The question “What is the opposition doing?” has now been replaced with “Is there a need for opposition?”

According to this new understanding formed over the political-social system, victory has united the people and eliminated the need for alternative ideas or organizations.

The post-opposition period is characterized not only by political repression and organizational weakening, but also by the loss of legitimacy of political pluralism and the automatic perception of alternative views as threats.

This is not connected with increased self-confidence of the regime, but with the strengthening of the security-based governance line in the post-victory period.

Conclusion

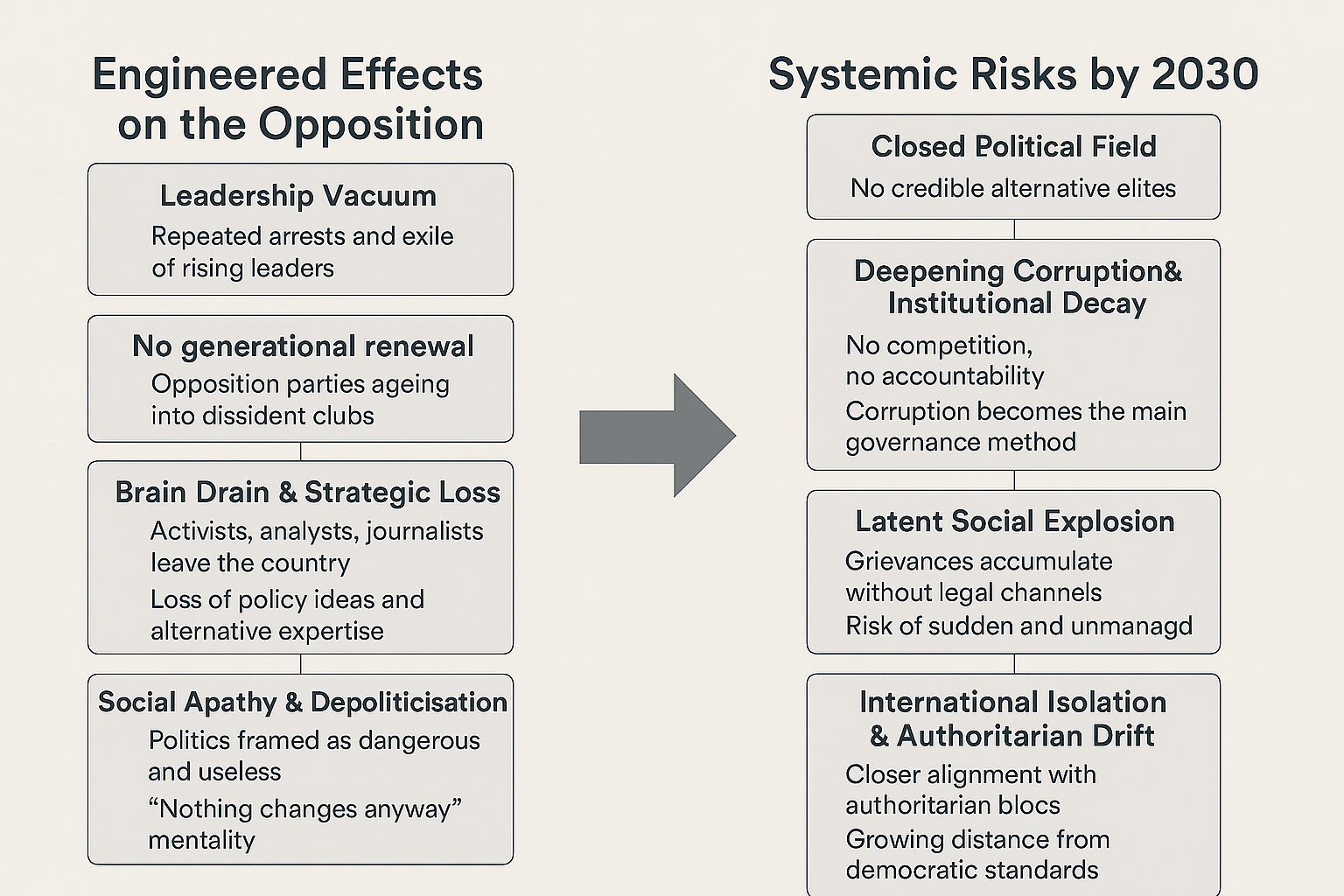

The artificial weakening of the opposition in Azerbaijan’s political system is a deliberate approach. This model has been formed as a long-term strategy based on legal, institutional, economic, and informational resources. The effects of this structure will appear more clearly by around 2030 in several fields. The system will be completely isolationist politically. The absence of competition makes the emergence of new ideas difficult, leading to a blockage of the decision-making process. This “freezing effect” significantly weakens the system’s ability to renew itself. With the elimination of the opposition, state structures will become even more corrupt. There is no accountability, no responsibility, and no competition — under such conditions, the weakening of state governance is inevitable. Corruption is not a byproduct of governance, but its main method. As the process deepens, the state structure loses its purpose and becomes only an instrument defending the interests of the ruling family and groups close to it. The deliberate exclusion of society from the system creates a vacuum in the social structure. A society that is distant from politics and has lost initiative also loses its capacity for self-governance. This prepares the country for delayed, unexpected, and uncontrollable social reactions. The regime thinks it is suppressing discontent, but in reality it accumulates it, creating a potential for sudden explosion. Internationally, Azerbaijan is moving towards authoritarian blocs. Continuous human rights violations and political repressions pull the country toward regions far from democratic standards. Although this process offers short-term opportunities for the regime, it will lead to the country’s isolation. The model of “artificial weakness” created by the regime conditions the emergence of serious dangers. As a result, an arrogant elite fed by power intoxication becomes unable to see realities, cannot understand the real problems they face, and rapidly loses governing capacity, while the entire system falls asleep under the illusion of stability. Hard authoritarian regimes are much weaker than they appear. Although they may remain standing for many years or even decades, their collapse is sudden. Azerbaijani authoritarianism also resembles the collapse model of traditional authoritarian regimes: a sudden crisis caused by internal decay and institutional degradation will trigger the collapse of the system.

References

Barbara Geddes, 1999. “What Do We Know About Democratization After Twenty Years?”. P 121. “Authoritarian breakdowns usually begin with elite defections rather than popular uprisings; mass protests tend to succeed only after divisions emerge within the ruling coalition.” https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.115

Andreas Schedler, 2002. “Elections Without Democracy: The Menu of Manipulation.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 36–50. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/elections-without-democracy-the-menu-of-manipulation/

Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski, 2006. “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 11 (2006): 1279–1301. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0010414007305817

Elman Fattah, November 2025a. The Stability and Legitimacy Mechanism of Azerbaijani Authoritarianism. https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-stability-and-legitimacy-mechanism-of-azerbaijani-authoritarianism

Kharcenter, May 2025a.The Evolution of Authoritarianism in Azerbaijan (Part I). https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-evolution-of-authoritarianism-in-azerbaijan-part-i

RFE/RL, 2003. Azerbaijan Report: https://www.rferl.org/a/1340716.html?utm_source=

Kharcenter, May 2025b.The Evolution of Authoritarianism in Azerbaijan (Part I). https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-evolution-of-authoritarianism-in-azerbaijan-part-i

Elman Fattah, November 2025b. The Stability and Legitimacy Mechanism of Azerbaijani Authoritarianism. https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-stability-and-legitimacy-mechanism-of-azerbaijani-authoritarianism

Trend, 2008. Venice Commission Thinks Changes in Azerbaijan’s Election Code Have Discrepancies. https://www.trend.az/azerbaijan/politics/1223285.html

ATƏT / DTİHB, 2010. Seçkiləri Müşahidə Missiyası Yekun Hesabat. https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/3/c/75655.pdf

HRVV, 2016. Harassed, Imprisoned, Exiled. Azerbaijan’s Continuing Crackdown on Government Critics, Lawyers, and Civil Society. https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/10/20/harassed-imprisoned-exiled/azerbaijans-continuing-crackdown-government-critics?utm_source

E-qanun, 2022. Siyasi partiyalar haqqında qanun. https://e-qanun.az/framework/53163

MEYDAN.TV, 2024. Political Activism Costs Jobs in Azerbaijan. https://www.meydan.tv/en/article/political-activism-costs-jobs-in-azerbaijan/?utm_source

HRVV, 2017. Azerbaijani Activist’s Family Arrested, Harassed. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/01/azerbaijani-activists-family-arrested-harassed?utm_source

Modern.az, 2013. Cəmil Həsənlinin mitinqində 1500 nəfər iştirak edib. https://modern.az/az/news/45243/?utm_source

sesqazeti, 2015. Müxalifət xarici təsir altındadır. https://sesqazeti.az/news/opposition/519178.html

Elman Fattah, November 2025d. The Stability and Legitimacy Mechanism of Azerbaijani Authoritarianism. https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-stability-and-legitimacy-mechanism-of-azerbaijani-authoritarianism

HRVV, 2013. Dozens of Activists and Journalists Jailed, Restrictive Laws Adopted. https://www.hrw.org/news/2013/09/02/azerbaijan-crackdown-civil-society

HRVV, 2024. “We Try to Stay Invisible” Azerbaijan's Escalating Crackdown on Critics and Civil Society. https://www.hrw.org/report/2024/10/08/we-try-stay-invisible/azerbaijans-escalating-crackdown-critics-and-civil-society?utm_source

Cəmil Həsənli, 2013. “Biz hakimiyyətin saxta müxalifət ideyasını darmadağın etdik”. https://musavat.com/news/gundem/biz-hakimiyyetin-saxta-muxalifet-ideyasini-darmadagin-etdik_167628.html

Sofie Bedford and Laurent Vinatier, 2018. Resisting the Irresistible: ‘Failed Opposition’ in Azerbaijan and Belarus Revisited. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/government-and-opposition/article/abs/resisting-the-irresistible-failed-opposition-in-azerbaijan-and-belarus-revisited/1816248B8594A09DBCB4665FCD0A2F04?utm_source

Elman Fattah, November 2025c. The Stability and Legitimacy Mechanism of Azerbaijani Authoritarianism. https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-stability-and-legitimacy-mechanism-of-azerbaijani-authoritarianism

Elman Fattah, Nov 2025. The End of Politics in Azerbaijan: The Beginning of a Post-Opposition Era. https://kharcenter.com/en/expert-commentaries/the-end-of-politics-in-azerbaijan-the-beginning-of-a-post-opposition-era