Author: Maryam Gholizadeh is a university instructor and academic researcher based in Ankara, Türkiye. She holds a PhD in Area Studies from Middle East Technical University, with a dissertation focusing on emotional transitions in social movements, specifically the case of Iran’s 1979 Revolution.

Abstract

The unanticipated fusion of scientism and theocracy in Iran has given rise to a distinctive form of ideology where the pursuit of scientific progress is taken as a form of religious obligation. This political framework is a tacit source of legitimacy for the clerical establishment as the opponents can no longer attack the Islamist for backwardness. By examining the Islamic Republic of Iran as an actual case, the current work explores the potential symbiosis between political Islam and scientism. The presented evidence highlights the unnoticed fact that in contemporary Iran the advancement of physical sciences has surfaced as a divine mandate and the primary source of Shia-Persian identity.

Introduction

In 2007, the Iranian government released a new 50,000 rial banknote featuring prominent scientific and religious motifs. The banknote’s design included a map of Iran superimposed with the schematic of electrons orbiting a nucleus, symbolizing atomic energy, accompanied by a calligraphic quotation of a hadith attributed to the Prophet Muhammad: “Men from Persia will acquire knowledge even if it is on Pleiades” (Jeffries 2007; Financial Tribune 2015). This design manifested the theocratic government’s vision of Iran’s national identity, based on scientific prowess blessed by divine sanction, and commemorated the nation's progress in nuclear technology as both a triumph of contemporary science and a realization of prophetic assurance. (Jeffries 2007). The incorporation of this specific hadith was significant because it suggested a superior status for the Iranian race, as conveyed through a divine medium, an act which contradicts mainstream Islamic beliefs, which stress the equality of all persons and believers (Wired, 2007). For example, both the Qur’an and the Prophet’s Farewell Sermon underscore that no Arab holds superiority over a non-Arab nor vice versa, except in terms of piety and virtuous deeds (Esack 1997, 98–104 Indeed, the hadith about Persian men reaching knowledge at the Pleiades is generally considered questionable and potentially a subsequent interpolation influenced by the early Islamic Shuʿubiyya movement – a 9th-century Persian cultural response to Arab dominance (Donner 2010). In the Abbasid period, Persian intellectuals and poets engaged in Shuʿubiyya aimed to affirm the value of non-Arab Muslims by highlighting Persian contributions to Islam and knowledge. The hadith extolling Persians’ quest for knowledge was probably popularized, if not entirely fabricated, in that context to bolster Persian reputation within Islamic discourse (Gellner 1997). The banknote was discreetly relegated to oblivion when the economic strain of international sanctions, ostensibly imposed owing to advancements in nuclear research, compelled the Islamic regime to adopt a more pragmatic approach. In 2015, amid the negotiations between Iran and 5 world powers (known as P5+1) over Iran’s nuclear program, the Central Bank of Iran quietly redesigned the contentious 50,000 rial banknote. The atomic orbit pattern and controversial hadith were supplanted by a far more benign motif, including the iconic entrance gates of the University of Tehran, accompanied by a couplet from the Persian poet Ferdowsi celebrating knowledge and wisdom (Linzmayer 2015). Although the official declarations said this was to commemorate the establishment of Iran’s foremost modern university, the timing and symbolism of the remodeling were broadly perceived as a surrender to Western pressure. The conservative newspaper Kayhan, sometimes serving as a conduit for Iran’s hardline factions, published a headline condemning the alteration. This domestic backlash underscored the extent to which the regime’s legitimacy was intertwined with symbols of scientific and technological accomplishments (Kayhan 2015).

The aforementioned instance vividly demonstrates the pivotal significance of scientism in the ideology of the Islamic Republic of Iran, characterized by an excessive dependence on scientific and technocratic assertions as the principal source of truth and legitimacy (Hudson Institute 2007). In essence, Iran’s post-1979 Islamist ideology demonstrates an “instrumentalist” perspective on modernity: it enthusiastically adopts science and technology as impartial instruments to empower the state, while dismissing the liberal or secular principles typically associated with modern science. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei in his regular sermons characterizes scientific advancement as a religious obligation, thus implicitly promoting scientism as a fundamental element of Iran’s theocratic-totalitarian agenda. Thus, the regime’s numerous technological initiatives, ranging from nuclear advancement to biomedical research, as not merely economically or militarily imperative but could be considered as a divinely sanctioned route to realize Iran’s revolutionary destiny. (Khalaji 2020, 55).

Iran’s prioritization on scientific achievement as a source of political legitimacy is not an isolated phenomenon. To support their legitimacy, many authoritarian and totalitarian governments have historically cloaked their ideologies in scientific jargon. For instance, Marxist-Leninist governments promoted "scientific socialism," claiming that their policies were founded on the immutable scientific laws of society and history. Communist nations used their rapid industrial and technological advancements in the middle of the 20th century to justify their one-party system of government. In the Middle East, secular autocracies like Nasser’s Egypt promoted science and industry (e.g., the Aswan High Dam, nuclear research facilities) as evidence of national advancement under "rational" governance (Encyclopaedia Britannica n.d.). Later on, Baathist Iraq under Saddam Hussein embarked on ambitious engineering initiatives to convey an impression of modernity. What distinguishes the Islamic Republic of Iran is that it blends authoritarian scientism with a religious framework, re-interpreted by the authority of the ruling jurists. Indeed, the Iranian Islamic Revolution has been characterized by scholars as a unique fusion of religious fundamentalism with the ethos of a modern revolution. Sociologist S.N. Eisenstadt noted that the Islamic Republic is “the sole lasting government formed by a contemporary fundamentalist movement, distinguished by certain features of notable modern revolutions yet driven by an extreme religious ideology (Amineh and Eisenstadt 2007, 137). The Iranian revolution, akin to those in France, Russia, or China, garnered substantial support by articulating utopian promises, pledging a comprehensive societal transformation, and establishing new political frameworks such as a parliament and presidency that diverge from traditional Islamic governance, yet remain under the supervision of the Supreme Jurist (Vali-e Faqih). The belief that an Islamic state will not only match but surpass the West in scientific pursuits due to its integration of empirical knowledge and ethical integrity corresponds with the esteem for scientific advancement. Subsequent to 1979, the Iranian government significantly spent in higher education and research, utilizing the ensuing progress to claim that an "Islamic Awakening" could achieve modern success akin to Western liberalism or Eastern socialism. The Iranian government endeavors to present itself as a pious yet progressive society by amalgamating Quranic references, hadith (irrespective of their veracity), and nationalistic motifs with emblems of contemporary technology. It asserts possessing both a spiritual mandate and the technological capability to guide the Muslim world.

The present study explores the crucial significance of scientism in the Islamic Republic of Iran and seeks to refute the erroneous characterization of this theocracy as a regressive state. This discussion examines how the scientistic ethos permeates the policies and rhetoric of the Iranian regime and its consequences for comprehending the nature of theocratic power in a contemporary context.

Conceptual Background: Scientism and Authoritarian Ideology in the Middle East

Scholars of Totalitarianism have long noted that extremist regimes claim that their ideological perspectives are substantiated by scientific evidence. For instance, according to Hannah Arendt both Nazi and Soviet ideologies justified their repression of dissent through purported natural or historical laws (Arendt 1951, 460–479). This dynamic can be noticed mainly in the Middle East through secular ideologies. These regimes publicly endorsed Western positivist scientism as their governing ideology, influenced by Marxism, social Darwinism, and European positivism. They argued that scientific development is the remedy to the "backwardness" that supposedly was affecting their constituents. In the political setting of the Middle East, there are several ongoing issues about the role of scientism, as shown below.

The "Scientific" Reason for Authority: Totalitarian administrations sometimes use the language of science, logic, or historical necessity to hide what they really want. For example, Atatürk's advisors used social science to explain why the fez was not allowed, and Nasser's planners used economic "laws" to justify one-party rule. The ayatollahs of Iran assert that Islamic law constitutes the paramount social science. Consequently, governments delegitimize resistance as uninformed or irrational by claiming sole authority over what they define as "scientific" truth. Michel Aflaq's notion that Ba'athism amalgamated science with the Arab ethos implied that any opposition was not merely a challenge to the dictatorship, but also to Progress and Rationality.

Technocracy and Repression: Many Middle Eastern authoritarian regimes have been highly technocratic, relying on experts and five-year plans. This can yield developmental successes (increased literacy and industrial growth) that the regime subsequently employs to bolster its legitimacy. However, the technocracy, devoid of accountability, as it is the norm in the Middle East, readily delves into authoritarianism. This aligns with Karl Popper’s critique of “utopian social engineering,” which states that attempts to reshape society wholesale often lead to tyranny (Popper 1945, 9–10). In the Middle East, authorities have rationalized the human costs of ambitious projects, such as forced resettlements for dams and the repression of labor unions for economic initiatives, as a necessary price for progress. Accordingly, they could dismiss dissenters as enemies of development.

Selective Embrace of Science: Authoritarian ideologues tend to differentiate between “useful” and “threatening” science. Physical sciences and technology are embraced as tools of national power, whereas social sciences are implicitly categorized as potentially threatening. Authoritarian regimes in the Middle East have initiated extensive literacy drives, established institutions (often prioritizing engineering over social sciences), and undertaken ambitious scientific projects (such as nuclear reactors, space programs, and large dams). The Islamic Republic of Iran serves as a pertinent example: Khamenei often lauds Iran's technological standing in areas such as nanotechnology and medicine to galvanize nationalist feeling. However, the regime rigorously censors or regulates disciplines such as sociology, history, and philosophy—any field capable of critically analyzing society or fostering divergent perspectives.

Millenarian and Utopian Overtones: Both secular and religious authoritarian ideologies in the Middle East possess a utopian element, vowing a near-messianic societal transformation through the proper implementation of their selected doctrine. Ba'athism advocated for an Arab renaissance; Islamists aspired to establish an ideal Caliphate or, in Shi'a interpretation, anticipate the Mahdi's return; even secular modernizers aimed to elevate their country to the status of great powers. Scientism fosters these utopian ideals by implying that the future is both foreseeable and alterable through adherence to "appropriate science." Khamenei's 50-year plan says that by 2065, Iran will be a major scientific power in the world and would help "global justice and peace" (Khalaji 2018). Notwithstanding, the literature is replete with examples of the disintegration of these utopian civilizations. Khalaji says that several cultural initiatives by Khamenei have "consistently failed over the past forty years," but the new structure substantially mirrors them. Dissenting intellectuals often refer to this disparity between utopian aspirations and practical shortcomings as a significant flaw of totalitarian scientism: human societies are too intricate and imbued with values that cannot be legislated. Iranian sociologist Asef Bayat contends that the Islamic Republic's failure to exert comprehensive control over daily life, shown by the dynamic underground culture of Iranian youth, reflects societal opposition to utopian governance. Even if these utopian ideals have failed before, they are still important. This shows how rigidly ideological governance driven by scientism can be.

Comparative Perspective: Not All Authoritarianism Is Equal: The literature provides a nuanced analysis indicating that the Middle East contains a continuum ranging from authoritarian regimes, such as pragmatic monarchies devoid of rigid ideologies, to totalitarian states, exemplified by Saddam's Iraq at its zenith and Khomeini's Iran during the Cultural Revolution in the 1980s. Scientism often characterizes the more ideologically motivated segment of this spectrum. For instance, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchs are authoritarian and draw their authority from dynastic and religious legitimacy. These governments employ Western knowledge in a practical manner without attempting to develop their own scientific philosophy. Saddam Hussein's Iraq, on the other hand, had a Stalinist cult of personality and built a "House of Wisdom" to celebrate Iraqi scientists. At the same time, it pushed the Ba'ath's objective of modernization. Consequently, scholars often differentiate pragmatic authoritarianism from totalitarian ideological regimes, the latter always using a kind of scientism or an all-encompassing dogma. Mehdi Khalaji asserts that Iran first functioned as a totalitarian state but has evolved after the death of Ayatollah Khomeini in 1988; by the 2010s, the Islamic Republic showed pragmatic inclinations via compromises motivated by survival, while maintaining a totalistic ideological self-perception (Khalaji 2023, 45–67).

Scientism as an Ideological Weapon (Anti-Islamic Narratives): Scientism may be utilized as a weapon by adversaries of specific regimes or religions. In essence, states utilize "science" to validate their authority, while critics and polemicists may employ science to undermine their opponents. Omer Kemal Buhari elucidates the concept of “scientistic anti-Islamism,” wherein the authority of science is used to depict Islam as fundamentally regressive or incompatible with contemporary society (Buhari 2019, 45). This story comes from 19th-century Orientalist philosophers like Ernest Renan, who said that Islam was against reason and development. Buhari's historical-philosophical examination reveals that current Islamophobic authors often assert that secular Western civilizations are "scientific" and rational, in opposition to Muslim cultures, which they see as ensnared in illogical pre-modern ideologies. He contends that such broad assertions are based not on facts but on ideology, as Qur’an includes over 700 allusions to knowledge (`ilm), a frequency far beyond that of other religious texts. The main point is that scientism, as a way of thinking, can be used to push any agenda, whether it is secular or religious, authoritarian, or prejudiced. In each instance, it entails an unjustified assertion of absolute truth that obstructs discourse.

Scientism and Totalitarian Tendencies in Iran

Much of the English-language scholarship on scientism and authoritarianism in the Middle East centers on Iran, due to its fluctuations between secular modernization and Islamic theocracy. Mehdi Khalaji, a theologian and analyst educated in Qom, offers a distinctive viewpoint on the manner in which Iran's authorities have utilized (or opposed) scientific notions to maintain ideological dominance (Khalaji 2023, 45–67). Khalaji and others trace this pattern through both the “Pahlavi era” and the post-1979 “Islamic Republic” as presented below.

The Pahlavi Modernization and Technocratic Authoritarianism

Under the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979), Iran’s rulers promoted a heavily secular, technocratic vision of progress. Reza Shah and his son Mohammad Reza Shah pursued rapid modernization by establishing factories, enhancing education, and empowering a Western-educated elite of technocrats. This modernization initiative was imbued with a scientistic ethos: society could be systematically constructed from above with the latest knowledge and technology. The Pahlavi regime, while not typically classified as "totalitarian," was authoritarian and justified its governance via development and scientific rationale. The regime frequently stifled dissent, regardless of its origins—Islamist, Marxist, or traditional—under the pretext of maintaining order and advancing progress. Modern Iran's pre-revolutionary development exemplifies a pattern recognized by social scientists: a modernizing regime that cultivated new educated and professional elites while denying them political engagement. The internal tension between the increasing demands of an educated populace and the Shah's unwillingness to relinquish control contributed to the revolutionary fervor of the late 1970s. Certain historians have likened the Shah's regime to Atatürk's Turkey due to its positivist influences, observing that the fixation on scientific advancement undermined political liberties. The literature on this time, such as the writings of Abbas Milani (Milani 2011) and Ali Gheissari (Gheissari and Nasr 2006), underscores the technocratic authoritarianism of the Pahlavi state, which, unlike subsequent totalitarian systems, lacked a singular coherent ideology beyond nationalism and modernization.

The Pahavi era was characterized by the rise of religious intellectuals and technocrats. Prominent among these, is Mehdi Bazargan, who established the groundwork for harmonizing Islamic principles with contemporary physical sciences. A devout Muslim and engineer educated at the École Centrale in Paris, Bazargan held the conviction that Islam and science were not only compatible but also mutually reinforcing. In his 1956 publication Eshq va Parastesh ya Thermodynamic-e Ensan (Love and Worship or the Thermodynamics of Man), he employed thermodynamic concepts as metaphors to elucidate human behavior and moral deterioration, positing that scientific rules reflected divine order (Taghavi 2004, 95). Bazargan's endeavors exemplified a wider initiative among Iranian reformists aiming to improve Islamic discourse through the integration of scientific thinking. Ali Shariati and other thinkers have spoken about the rational and transformational portions of Shi'a theology in order to create a contemporary society based on Islamic values (Abrahamian 2008, 126–133). These early efforts made it possible for the Islamic Republic to subsequently use science as a vehicle for strategy and ideology, even though it was a theocracy (Amineh and Eisenstadt 2007, 137–139).

The Islamic Revolution: Rejection and Appropriation of Scientism

After the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers completely rejected the West's secular scientism, on the grounds that it was corrupt and too focused on worldly matters. In contrast, intellectuals wanted to combine Islam with science and progress.

As the regime consolidated power, the revolutionaries promoted the view that science and technology should be used to serve people spiritually instead of becoming ends in and of themselves. This meant that scientific work that was in line with Islamic values was more significant than work that was seen to foster Western materialism or moral deterioration. Thus, while condemning Western scientism, the Islamic Republic fostered its variant of scientism: the conviction that Islam offers a comprehensive system of knowledge—essentially a “science of society” directed by the clergy. Khomeini’s ideology of Velayat-e Faqih (Guardianship of the Jurist) conferred ultimate authority upon a religious jurist to enforce divine law as the paramount political leader. Khomeini quickly saw that many classical Islamic laws were not useful for running a modern state. This led him to come up with the idea of "Maslehat-e Nezam" (regime expediency), which is basically a reason for the state to allow the Supreme Leader to ignore religious rules when it is in the regime's best interests. This action, albeit framed in Islamic terminology, resembles a totalitarian adaptability: the state's ideology can supersede any standard in the interest of its preservation. The Islamic Republic consequently placed its religiously constructed "science" of society above all else, tolerating no legal or institutional constraints—a characteristic of totalitarian governance. Consequently, the Islamic Revolution should not be perceived as anti-modern in a simplistic manner. Amineh and Eisenstadt assert that Khomeini’s movement emerged amid the proliferation of modernity, utilizing numerous structural and organizational elements of modernity, particularly the media and contemporary organizational techniques for mass mobilization (Amineh and Eisenstadt 2007, 132–134). The new government used modern political mechanisms including a parliament and president, which are not part of traditional Islamic governance. Iran's revolution was different from past secular revolutions because it employed contemporary techniques to promote an anti-Western, quasi-theocratic worldview. It also had a strange blend of modern form and anti-modern spirit. Khomeini's Islamic Republic adopted the tactics of modern scientism, including extensive education, centralized planning, and propaganda, while simultaneously repudiating its secular-humanist principles. Some individuals have labeled the 1979 revolution a "modern fundamentalist" movement since it mixed modernity with anti-modernity.

Khamenei’s Ideological Mindset: Fundamentalism Meets Technology

Since Ayatollah Ali Khamenei became Supreme Leader in 1989, the Islamic government has intensified its ideological control and pursued selective scientific progress. Mehdi Khalaji's recent endeavors, including a 2023 political biography of Khamenei and policy analyses for The Washington Institute, underscore Khamenei's dual vision for Iranian power (Khalaji 2023, 67): “total Islamization of all facets of life” combined with aggressive pursuit of modern science and technology. In an influential 2018 speech, Khamenei unveiled an “Islamic-Iranian Blueprint for Progress” for the next 50 years. At its core, the blueprint seeks an ever-deeper “marriage of fundamentalist ideology and modern technology” to achieve Iran’s supremacy. On one hand, Khamenei insists on the “total Islamization” of culture, education, and governance, rejecting Western political and social norms. On the other hand, he places heavy emphasis on “advanced scientific achievements” to make Iran “technologically self-reliant.” The end goal, as the document proclaims, is for Iran to become one of the world’s top five countries in science and technology while serving as the ideological vanguard of a new Islamic civilization. This blend of theological absolutism with technocratic ambition is characteristic of what Khalaji terms Khamenei’s totalitarian mindset.

Khamenei has really been attempting to make this way of thinking a part of Iranian society. He made it his goal to use Iran's most significant institutions, including the Revolutionary Guard and the education system, to spread his ideas right after he took power. Khamenei gave the whole government the job of building an ideological apparatus that could carry out his totalitarian policies and fight the West's supposed 'cultural invasion (Khalaji 2007). Consequently, critics were suppressed, and it was made sure that schools, the media, art, and even scientific study all conform with the ideological framework set forward by Khamanei. Universities were pressed to purge “Westoxicated” professors and Islamize the humanities curricula on the grounds that Western social sciences spread secular and liberal ideas. During the Ahmadinejad presidency (2005–2013), this campaign intensified. Khalaji notes that President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad viewed the social sciences as Western products alien to Iran’s Islamic identity. Ahmadinejad and like-minded hardliners argued that Islamic sciences—rooted in Shi’a theology and Quranic principles—are fundamentally different from Western sciences. Such views justified policies like restricting teaching in certain disciplines, including law, sociology, philosophy, etc, to an approved Islamic perspective (Khalaji 2023, 84–89).

Ironically, although Iran's leaders condemn Western scientism, they readily utilize scientific terminology to validate their governance. The administration often emphasizes its accomplishments in nuclear technology, aerospace, and medicine as evidence of "scientific" competence, while simultaneously suppressing scholarly exploration in the social domain. Khamenei's plan asserts that by 2065, Iran will generate advanced "Islamic humanities" and achieve a leading position in scientific production and Islamic ethics (Khalaji 2018). This reflects that totalitarian governments selectively adopt scientific disciplines—favoring technological and military sciences to enhance state authority, while rejecting sciences (or scientific principles such as open inquiry) that jeopardize ideological dominance. In Iran, hardliners exalt physics and engineering, particularly when used in the context of defense industries, while denouncing secular philosophy and political science as subversive. The political significance of scientific advancement is so evident that it becomes interwoven with nationalist ideology as we described above in the case of the 50,000 rial banknote. This story clearly demonstrates that science and technology, particularly nuclear technology, serve not only practical purposes in Iran but also act as ideological symbols that the dictatorship claims are sacred representations of its legitimacy.

Several Iranian scholars have described Khamenei as a figure who merges authoritarianism with an intense reverence for scientific progress, noting the contradictions within his ideological stance. In an episode broadcast on BBC Persian, Mehdi Khalaji referred to the regime as Jomhouri-ye Elmparasti, translating to “The Republic of Scientism.” This label reflects a broader perception that Khamenei presents himself as a forward-looking leader who champions scientific advancement and sees technological development as a tool for consolidating political influence (Khalaji 2010). Khamenei frequently emphasizes the value he places on research and innovation, particularly urging the younger generation in Iran to excel in cutting-edge disciplines like nuclear science and nanotechnology. Even as he promotes these ambitions, his speeches often include sharp criticisms of Western dominance in global affairs. This fervent belief in science and technology, provided they are Islamicized and regulated, demonstrates that the Supreme Leader's perspective is not inherently anti-modern; rather, it aspires to a distinctive Iranian-Islamic modernity capable of competing with the West. The problem, as shown in the literature, is that when a government "venerates" science in this manner, science becomes a tool of ideology—lauded when it supports authority, repressed when it contests the sanctioned narrative.

Manifestation of scientism in contemporary Iran

Prior to the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran's scientific and higher education system was deficient and predominantly reliant on knowledge acquired from foreign nations. For instance, during the academic year 1979–80, Iran dispatched the highest number of foreign students to the United States, where more than fifty thousand young people from Iran were already attending universities. In 1977, Iran only had 16 universities, with 154,000 students, most of whom were enrolled in undergraduate programs (Amineh and Eisenstadt 2007, 132–133). In order to sustain a country's needs in critical fields like energy, the military, and healthcare, the government depended on expertise and technology brought in from other nations. In addition, during the Pahlavi era, educational institutions prioritized themes of modernization and alignment with Western ideals. However, they fell short of investing strategically in research and development and made little effort to promote the spread of knowledge or innovation within local communities (Mehran 2009, 544–546).

The establishment of Islamic government was followed by a few tumultuous years, when the universities were closed with the goal of Islamization. Once the universities re-opened in 1983Iran's higher education system started rapid growth. By the early 2000s, it had expanded from a consortium of 16 universities with approximately 154,315 undergraduate students in 1977 to a network comprising hundreds of higher-education institutions. By the mid-2000s, over 60% of all college students and almost 70% of STEM[ST1] students were female. UNESCO data from the 1990s onward indicates that the ratio of women to males has remained over 50% for numerous years. It is ironic that most university graduate women remain unemployed or underemployed despite academic credentials. State propaganda frequently employs enrollment statistics as evidence of scientific and contemporary advancement (Mehran 2009, 547–550).

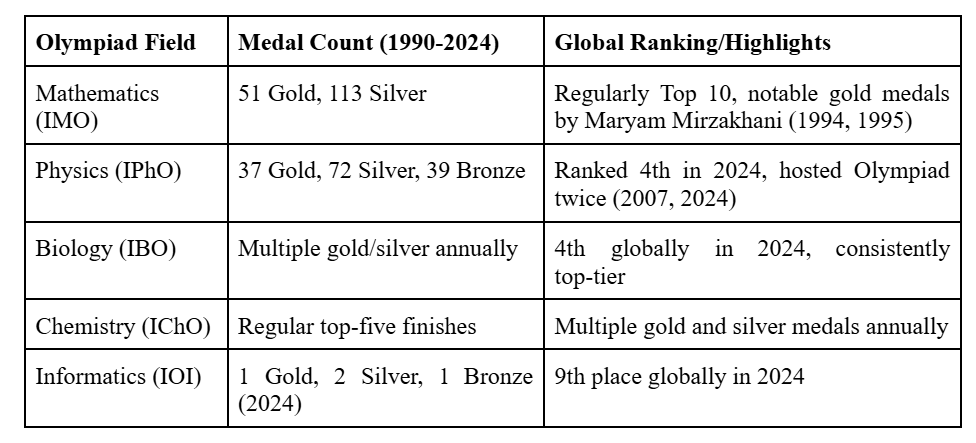

In the 1990s, Iran made a systematic national strategy to discover and prepare young individuals to compete in international scientific Olympiads. One of the most important elements of this endeavor is the National Organization for Development of Exceptional Talents (NODET), which was established in the 1980s. This establishment is associated with elite high schools, known as "SAMPAD", which focus on advanced level math, physics, biology, chemistry, and computer science. The students are selected by nation-wide competitive entrance exams by the Ministry of Education. The result is the excellent standing of Iranian students in math and science Olympiads, as can be seen in the table below. Indeed, Iran is constantly among the top ten countries in the world for Olympiad performance (IRNA, 2024). Some of the participants became recognized all around the country (Coghlan 2011). Among these, Maryam Mirzakhani is the most well-known for her achievement. She won two gold medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO). Then, she left for the US for graduate studies and stayed there after getting her PhD. Apparently, her mission as a propaganda tool was concluded and there was no demand for achievements in Iran.

The Islamist government demonstrates a marked preoccupation with Ph.D. credentials and ISI-indexed publications, more likely for ideological and professional validation rather than authentic intellectual contribution. This is evidenced by legislation mandating a master's degree in science as the minimum educational qualification for candidates seeking election to the Islamic parliament. Consequently, during the vetting hearings for ministers of new governments, those lacking Ph.D. degrees face no prospects. A side effect is the unparalleled prestige associated with publishing in Web of Science–indexed journals as a criterion for promotion, resulting in an increase in publication volume and frequently, plagiarism, with Iran lately ranked among the leading nations for retracted publications (Dadkhah, Borchardt, and Maliszewski 2016, 1615–1620). This credential-centric society mirrors wider regional trends often termed “Jordanism,” wherein holding a foreign degree or the title “Dr.” bestows status irrespective of actual merit. The regime simultaneously emphasizes significant technological achievements—such as nuclear capability, the Royan Institute's cloning of sheep in 2006, and leadership in nanotechnology research. These are depicted in state media as evidence of national self-reliance, thereby integrating technical prestige into its ideological narrative (Ghazinoory, Divsalar, and Soofi 2009, 840–845).

Conclusion

The symbiotic integration of scientism with theocracy in modern Iran has established a unique ideological framework, wherein scientific and technical progress serves as fundamental components of religious legitimacy and national pride. The Iranian leadership has effectively incorporated scientific language into its central narrative by portraying advancements in nuclear technology, nanotechnology, cloning, and space exploration as a divine mandate and a means of resisting Western hegemony. This selective endorsement of science involves contradictions: while the natural sciences flourish, the social sciences and humanities are strictly constrained or suppressed to maintain ideological purity. Furthermore, the regime's preoccupation with credentials—particularly Ph.D. qualifications and ISI-indexed publications—exhibits an ironic dependence on Western academic validation, reflecting regional phenomena such as "Jordanism," where elite status is often linked to foreign degrees and academic excellence. Iran's experience ultimately illuminates the intrinsic contradictions and paradoxes that arise from authoritarian ideologies using scientism to assert absolute facts. This method may bolster immediate legitimacy but compromises genuine innovation and societal progress by imposing rigid ideological constraints on scientific inquiry, hence fostering potential instability and discontent among a more informed yet disillusioned people.

References

Abrahamian, Ervand. 2008. A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Amineh, Mehdi Parvizi, and S. N. Eisenstadt. 2007. “The Iranian Revolution: The Multiple Contexts of the Iranian Revolution.” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 6 (1–3): 129–157. https://doi.org/10.1163/156914907X207702.

Arendt, Hannah. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Buhari, Ömer Kemal. 2019. “Scientistic Anti-Islamism: The Exploitation of Science and Cognates in Anti-Islamic Narratives.” Islamophobia Studies Journal 5 (1): 45–60.

Coghlan, Nicholas. 2011. “Iran’s Gifted Student Program Bears Fruit.” Nature News, July 20, 2011. https://www.nature.com/articles/news.2011.430.

Dadkhah, Mehdi, Götz Borchardt, and Tomasz Maliszewski. 2016. “Fraud in Scientific Publications in Iran: The Need for a Revised Policy.” Science and Engineering Ethics 22 (6): 1613–1627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9721.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. n.d. Totalitarianism. Accessed August 5, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/totalitarianism.

Ghazinoory, Sepehr, Ali Divsalar, and Abdol S. Soofi. 2009. “A New Definition and Framework for the Development of a National Innovation System: The Case of Iran.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 76 (6): 835–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2008.10.004.

Jeffries, Stuart. 2007. “Iran’s New Banknote Goes Nuclear.” The Guardian, March 14, 2007.

Khalaji, Mehdi. 2010. House of the Leader: The Real Power in Iran. PolicyWatch No. 1524. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 7.

Khalaji, Mehdi. 2007. "'Bad Veils' and Arrested Scholars: Iran’s Fear of a Velvet Revolution." PolicyWatch, May 24. Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Khalaji, Mehdi. 2018. “Iran’s Anti-Western ‘Blueprint’ for the Next Fifty Years.” The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, October 24. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org.

Khalaji, Mehdi. 2020. Iran’s Republic of Fear. The Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

Khalaji, Mehdi. 2023. The Regent of Allah: Ali Khamenei’s Political Evolution in Iran. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Linzmayer, Owen. 2015. “Iran new 50,000‑rial University of Tehran commemorative note (B290a).” BanknoteNews, October 31.

Mehran, Golnar. 2009. “Doing and Undoing Gender: Female Higher Education in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” International Review of Education 55 (5–6): 541–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-009-9145-0.

Milani, Abbas. 2011. The Shah. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Randal, Jonathan. 1979. “Islamic Revolutionaries Plan a New Science for Iran.” Nature 282 (5739): 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/282009a0

Taghavi, S. Mohammad. 2004. “The Flourishing of Islamic Reformist Thought in Iran: Bazargan and the Thermodynamics of Human Beings.” Islamic Studies 43 (1): 95–113.

Wired. 2007. “Iranian Bank Note Goes Nuclear.” March 12, 2007.