Abstract

Thirty years ago, the collapse of the Soviet Union sparked hopes that new democratic states would emerge from the ruins of the so-called "evil empire." However, history has shown that the end of a totalitarian regime does not necessarily mark the beginning of democratization. True transition entails fundamental and systemic changes in a political structure. A political system based on democratic and inclusive principles implies tolerance of opposition, the existence of pluralistic institutions, competition, and most importantly, the peaceful and lawful transfer of power based on electoral outcomes.

However, the system brought by the new rulers of Russia—the largest successor state of the USSR—initially displayed a seemingly different form and an imitation of democracy. In reality, it transformed into a rigid structure that transitioned from totalitarianism to authoritarianism, supported by the remnants of the old nomenklatura. Since 2008–2009, democracy in Russia has declined both quantitatively and qualitatively (Civil.ge 2024). In parallel, Moscow’s efforts and influence aimed at weakening democracy across the post-Soviet space began to grow.

The political system established in Russia has shaped other post-Soviet republics, including Azerbaijan. Over the last two centuries, fundamental political developments in Russia have not only prompted changes and new formations in Azerbaijan’s socio-political life but have also often served as a model. Whether under Tsarist Russia, Soviet Russia, or Putin’s Russia, the patterns of public and political behavior have taken shape in Azerbaijan, reflecting each era’s specific adaptations and similarities.

For this reason, in order to understand the political system and the nature of governance in authoritarian-leaning states such as Azerbaijan and other post-Soviet republics, it is first necessary to study Russia’s political system, to understand how it operates, and to explore its political science foundations.

In this research, the Khar Center investigates Russia’s political system.

Objectives of the Research:

- To analyze the core features of Russia’s current political system.

- To uncover how and why this system exhibits authoritarian characteristics.

- To assess its influence on the post-Soviet space, particularly on Azerbaijan.

Research Questions:

- What are the main structures and mechanisms of the Russian political system?

- How does Russia implement the imitation of democracy?

- How has this model influenced the political structures of post-Soviet countries, particularly Azerbaijan?

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

- Type and Approach of the Research

This research is qualitative, analytical-political, and theoretical-analytical in nature. The aim is to structurally analyze Russia’s political system and identify its authoritarian features. - Methodological Framework

Systems Approach: The political system is analyzed as a comprehensive structure — institutions, normative frameworks, decision-making mechanisms, and their interrelations.

Keywords: Russia, political system, authoritarianism, managed democracy, post-Soviet space, Azerbaijan, political institutions.

Introduction

The Russian Federation — the largest state in the post-Soviet space — is sometimes compared to the fragile democratization processes of today’s Moldova and Ukraine. However, due to the continued dominance of the old elite and the preservation of their methods in the governance system, it can be said that the democratization process in Russia did not materialize and the reforms remained largely cosmetic. In other words, the Russian case is not an example of democratic backsliding, but rather an example of democracy never actually beginning (Snegovaya 2023). Still, it is important to emphasize that it was not merely the old elite, but primarily the factor of leadership that shaped the changes.

In the 1991 presidential elections, Boris Yeltsin won with 59% of the vote and came to power with a reformist team. However, the opportunities for enrichment brought about by the reforms, as well as his personal characteristics, made him weak in his role as head of state. According to proponents of situational leadership theory, Yeltsin may have succeeded in proving himself as a leader in the early 1990s because he responded to the demands of that particular situation. But history showed that he lacked the leadership qualities necessary for the next phase — completing the reforms and advancing the democratization process.

If we compare Boris Yeltsin, the new leader of resource-rich Russia, with 1960s Singapore — a poor country with no resources and even unable to provide its population with drinking water — we find that in the person of Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore had a leader whose political vision and willpower were perhaps the most critical factors in successfully carrying reforms through to the end. While the example of Lee Kuan Yew shows us a leader who even sacrificed his closest friends to eradicate corruption, the example of Boris Yeltsin reveals the opposite: a leader who created opportunities for his close circle to enrich themselves, thereby transforming corruption into a mechanism of power and laying the foundation of an extractive political system (Radio Svoboda 2015).

Yeltsin’s successor, Vladimir Putin, inherited not only political power but also this new oligarchic system — and he further “refined” it. The old nomenklatura, which had grown wealthy during the reforms of the 1990s and established control over industry and finance, carried criminal elements and lacked any coherent ideology. They held sway over the State Duma and were capable of confronting the reformist elements within the government.

However, the oligarchy — which during the Yeltsin era reflected the features of what was called “bandit capitalism” — was replaced during Putin’s rule by a model resembling “Asian capitalism” (Radio Free 1997). Thus, immense wealth once again concentrated in the hands of a small elite, while the majority of the country remained impoverished. The fundamental difference from the previous period was that this oligarchy was no longer anarchic — it was subordinate to a single center of power.

Putin strengthened autocracy by using harsh repressive tools against his critics and turning state-controlled media into a propaganda and disinformation apparatus. The expropriation of Russian oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s business, the murder of journalist Anna Politkovskaya, the assassination of opposition leader Boris Nemtsov near the Kremlin walls, and the poisoning of Alexei Navalny are all visible signs of the Putin regime’s governance. However, these and other indicators provide a foundation for forming thoughts and assessments about the new political system he has built.

THE ESSENCE OF THE POLITICAL SYSTEM IN RUSSIA

According to its Constitution, the Russian Federation is a democratic federal legal state with a republican form of governance. Russia’s definition as a democratic state is grounded in the provision that the sole source of authority is the people (Constitution of Russia). Furthermore, it states that the people exercise this authority through elections and via organs of state power and local self-governance. Under the Constitution, state power is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial.

Russia’s identity as a federal state is reflected in its constitutional structure. The Russian Federation comprises republics, territories (krai), regions (oblast), cities of federal significance, an autonomous region, and autonomous districts. These federal subjects have their own state institutions with specific powers. Within their jurisdictions, they exercise authority within the scope of their competencies. The status of these subjects is defined not only by federal legislation but also by the constitutions of republics and the charters of territories, regions, and cities of federal significance. This federal structure is also reflected in the bicameral legislature, composed of the Federation Council and the State Duma.

At the head of the executive branch stands the President of the Russian Federation. While the legislative branch is formally independent, in practice it operates under the influence of the executive. The president holds extensive powers and is the central figure of the executive branch. Although federal subjects possess formal autonomy, they are de facto under the control of the central government.

The Constitution also states that the Russian Federation recognizes ideological and political diversity, including a multi-party system. However, despite the formal existence of a multi-party system, in practice the ruling “United Russia” party holds a hegemonic position, and active opposition political forces are nearly non-existent as political actors.

Thus, although Russia is formally a semi-presidential republic, its political system is in practice far removed from democratic principles. While some attempt to portray today’s Russia as a “strange symbiosis of democracy and authoritarianism” — a hybrid regime — the reality is that it exhibits the features of autocracy, dictatorship, criminocracy, and mafia statehood (Krasin 2004).

Key characteristics of contemporary Russian governance include:

- Personalization of power and the authoritarianism of the top state official;

- Plebiscitarianism, where candidates appointed from above are ostensibly “approved” by the population through elections;

- Absence of genuine opposition and a non-democratic political environment;

- Exclusion of civil society from political participation, with the creation of state-controlled pseudo-civic elements;

- Subordination of local government structures to the central state apparatus.

The defining element of Russia’s political system is the supremacy of the state over society. By exercising political authority, the state dictates behavioral norms. In other words, “the state claims a monopoly on the legitimate use of physical and symbolic violence within a given territory and against the relevant population” (Irkhin, Zotov, and Zotova 2002).

The tools and mechanisms used in governance exhibit the classic traits of authoritarianism. For instance, while Russia officially maintains a multi-party system, in reality a hegemonic party system has developed — true pluralism can only exist if multiple parties can compete for power under equal conditions. In Russia, only one party — “United Russia” — holds actual political power. Other parties represented in the Duma act as satellites of the Kremlin, lacking both autonomy and the ability to influence the broader public.

From Putin’s first presidential term, under the guise of “restoring state authority” and slogans like “dictatorship of law,” the system began shifting rapidly toward authoritarianism. The strategy was to preserve the appearance of democracy while hollowing out its institutions from within. This imitation-based political system was marketed to society under the term “sovereign democracy,” alongside calls to rally around the leader against foreign threats and sabotage (Radio Svoboda 2006). The president’s actions were presented as aligned with public will: “Today the government is doing what the people want.” Analysts framed this as a culturally specific interpretation of democracy: “Values native to us are accepted, while those foreign to our spirit are rejected. A kind of natural selection of democratic elements offered by the government takes place... Today we observe a significant authoritarian demand within society” (Shestopal 2004, p. 28).

During this period, nationalist political figures like Russia’s NATO ambassador Dmitry Rogozin called on all nationalists to join the government to help restore Russia’s status as a great power (Hassner 2008). Nationalism was actively promoted, and even fascist tendencies began to emerge. Ethnic discrimination, which initially targeted peoples of the Caucasus, later expanded to other non-Slavic groups. In major Russian cities, youth groups such as skinheads and Limonov followers marched openly with fascist symbols — guided by invisible hands.

The model branded as “sovereign democracy” actually bore the marks of autocracy long studied in political science. In personalist autocracies like Putin’s Russia, political power is rooted in informal relationships, which undermines state institutions. As political scientists note, “weak state institutions enable the autocrat to seize power but make governance more difficult” (Hassner 2008). Thus, the system shifts from law-based mechanisms to one-man authoritarianism.

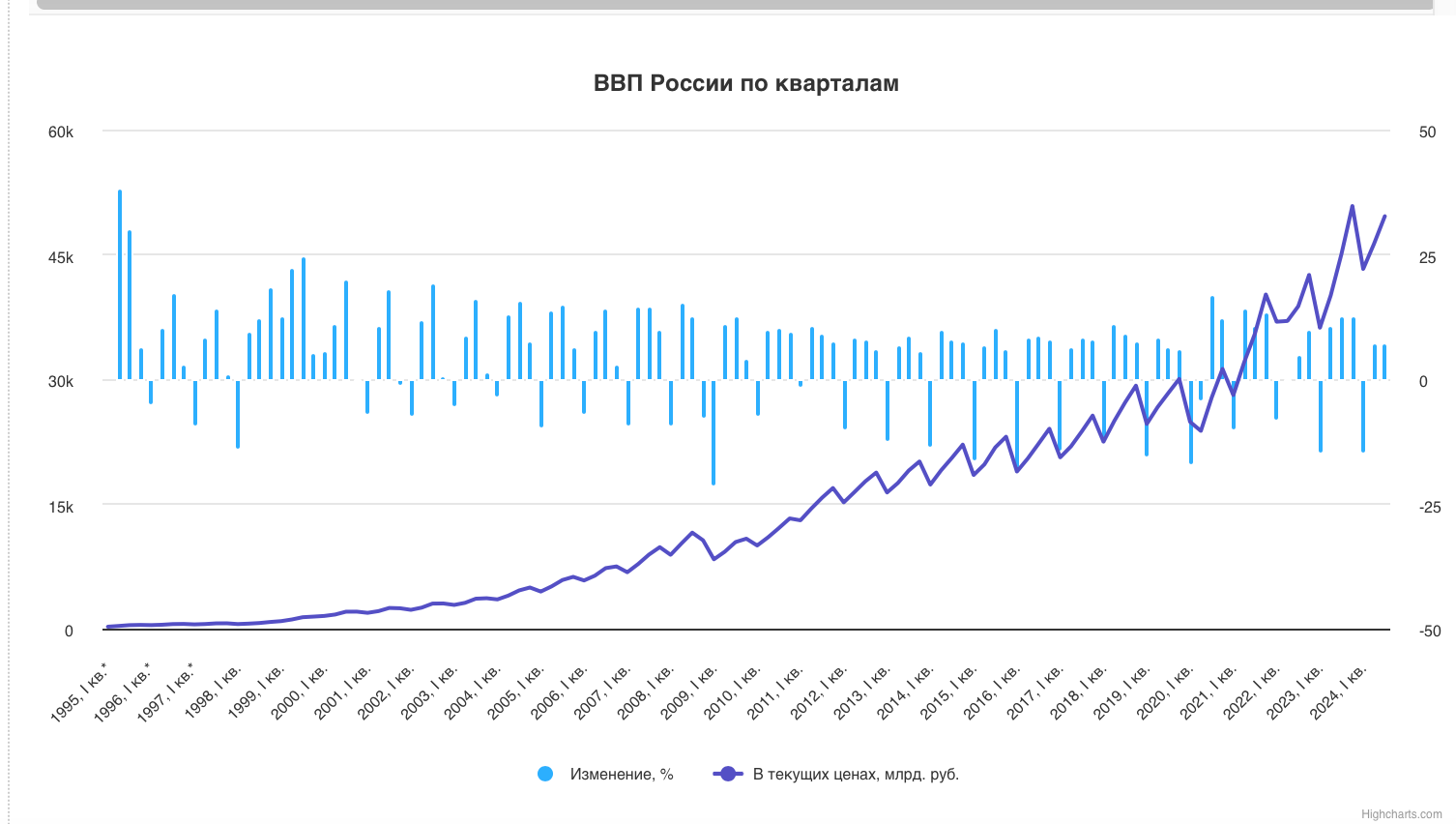

Putin governs the state’s economic, financial, social, and security institutions through networks of mutual dependency with loyal elites. Yet despite this massive power, weak institutions limit his capacity to resolve problems and achieve goals. Moreover, the dependency of everything on one person places the wealthy elite in a precarious position — the system functions for them only as long as Putin remains in control. In personalist autocracies, when the leader must choose between the welfare of his inner circle and that of society, the elite always wins. The systemic extraction of public resources through corruption not only erodes economic indicators but also deepens the rift between the state and society. From 2003 to 2008, when Russia’s economy grew at an average of 7% annually due to high oil prices, Putin was able to both enrich the elite and improve living standards for the population (GOGOV n.d.). (Table 1. & Graph 1.)

(Table 1.)

(Table 1.)

(Graph 1.)

(Graph 1.)

However, the 2008 global financial crisis, the international sanctions imposed following the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the pervasive, immeasurable corruption all dragged down the economy. This demonstrated how “bandit capitalism” renders state institutions dysfunctional.

Modern Russia’s political system, with its embedded criminal elements, is also classified as a criminocracy (Karolewski and Kaina 2023). In a criminocracy, elections, parliaments, and courts exist only to simulate democratic legitimacy; in reality, power is seized by members of a criminal network. Putin’s Russia manifests criminocracy not only in elite corruption but in state-enabled crimes of grave magnitude. These include war crimes in Ukraine — the abduction of Ukrainian children to Russia, mass rapes and killings in towns like Irpin and Bucha — as well as war crimes committed against civilians in Chechnya and Syria, the operations of the Wagner Group in Africa’s diamond and gold sectors, and the criminal actions mentioned earlier.

A mafia state, like criminocracy, is essentially understood as governance by a criminal syndicate (Madiyar 2016). In Russia, power has been built upon principles belonging to criminal clans, where personal loyalty plays a key role in the system of relations, and laws are applied in accordance with the interests of the "patron" and his close circle. In a mafia state, corruption is not a deviation from the norm but rather a constitutive element of governance. The essence of the mafia state in Russia lies in the fusion of power and criminality, evident in racketeering practices (e.g., the seizure of private oil company Yukos, criminal cases against Boris Berezovsky and Vladimir Gusinsky and the expropriation of their businesses), the poisoning or murder of political opponents (such as Alexei Navalny, Vladimir Kara-Murza, Boris Nemtsov), the enrichment of the ruling elite (Putin’s palace, profits of his close associates from state contracts), and in military operations, such as Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin's recruitment of thousands of prisoners.

How has the political system changed in modern Russia?

Although Russia displayed certain democratic features during its first decade of independence, the democratic process had not fully materialized. Russia's democratic trajectory derailed even before Putin, when in 1993 Boris Yeltsin ordered the military to shell the rebellious parliament. Moreover, the Constitution adopted that same year consolidated Yeltsin's power and enabled the establishment of a "formally democratic, substantively authoritarian political regime" (Smolin 2006, 203-204). During this period, the Russian political system was characterized by a mix of mutually exclusive principles of a hybrid regime. On one hand, the personalization and indivisibility of power were clearly visible; on the other hand, this personalized power was formed and legitimized through democratic means (Shevtsova 2004, 47). Nevertheless, the failure of democratic institutions to develop led to widespread disillusionment and the emergence of public demand for a "strong hand," fostering hope that an authoritarian leader could restore stability and order (Shevtsova 2007). The 1996 re-election of Yeltsin marked the peak of this democratic crisis. Despite having the lowest approval ratings, oligarchs engaged in massive fraud to secure his victory. As a result, governance in 1990s Russia reflected characteristics that were contrary to the Constitution:

- Expansion of presidential powers at the expense of other branches;

- Nominal character of power separation;

- Authoritarian-oligarchic forms of governance masked by elements of democratic procedure, especially elections and a multiparty system;

- Concentration of power in a narrow circle of nomenklatura and large property owners who had gained wealth illegitimately, resulting in the use of criminal methods in governance.

As the old nomenklatura retained significant weight in the system and relied on loyalty, entry into this circle from the outside was very difficult. The economic collapse of the early 1990s could not be resolved even by "shock therapy," as the old elite and the president's entourage seized state assets and privatized infrastructure, obstructing reform success (Temmer 2014). The new capitalists realized that their interests aligned with those of state officials, and thus succeeded in limiting democratic reform tendencies and discrediting reforms in the eyes of the public (Snegovaya 2023).

The meteoric rise of former KGB officer Vladimir Putin from aide to the mayor of St. Petersburg to the highest state office was a direct result of these circumstances.

The new political system associated with the new president began forming after the 2000 presidential elections. However, even before the elections, the new leader’s political style had begun to take shape, significantly determining new methods of governance. Therefore, Putin quickly emerged as the dominant figure upon assuming the presidency (BBC 2024). Simultaneously, signs emerged of a departure from the core principles of competitive politics:

- A sharp weakening of the political influence of regional elites and big business;

- Establishment of direct or indirect state control over major national television channels;

- Increasing use of "administrative resources" in regional and federal elections;

- De facto elimination of power separation;

- Emergence of non-public political behavior (Urnov and Kasamara 2005, 26-27).

A crucial stage in the formation of the new political regime was the 2003 parliamentary elections, after which "parliamentarism with real opposition representation disappeared" (Yakovlev 2005, 11). The United Russia party, declaring full support for the president’s policy, obtained a constitutional majority in the State Duma, granting it unrestricted means to reshape the political system and subject it entirely to Putin.

The system shaped by the new president began to be referred to as "Putinism," denoting both the regime and the president’s ideology in contemporary Russia (Nikonov 2003, 29). Drawing on nationalist rhetoric, Putin transitioned to total militarization after launching the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. He now presents himself as the leader who rescued Russia from economic, social, and political crises and defends national interests against the West.

Putinism and the early development of legislative authoritarianism in Russia

When the USSR collapsed, Russia consisted of 80 regions, divided into donor and recipient regions (Collective of Authors 2002). Until the early 2000s, regional leaders were directly elected by local constituents. On May 13, 2000, Putin introduced the institution of presidential envoys in federal districts (President of Russia, 2000). Their main tasks were to subordinate local legislation to federal law and unify regional governance, thereby establishing vertical authority. Many regional legislative acts were annulled as a result.

The 2004 Beslan terrorist attack served as a pretext for President Putin to announce a new package of political reforms. On September 3, Putin declared that, given the sharp rise in terrorism, the executive system needed fundamental restructuring to strengthen unity and prevent crises (President of Russia, 2004). As a result of this restructuring, executive authorities at central and district levels were to function as a unified coordinating body. "The highest officials of the founding entities of the Russian Federation would be elected by regional legislatures upon nomination by the president."

A key moment in the transformation of the Russian political system in the early 2000s was the abolition of direct gubernatorial elections and the intensification of centralization (TASS, 2013). Although direct gubernatorial elections were reinstated in 2011, only candidates from parties represented in the federal legislature were allowed to participate.

The 2010s saw the abolition of the elected mayoral institution in many local cities. Two institutions that had previously been legitimized through elections were subordinated directly to the federal government. Nevertheless, the direct election of mayors was preserved in 14 Russian cities.

Another characteristic of this period was the central collection of revenues, which were redistributed by the federal center among regions. This ensured the strengthening of central power and made regional authorities completely dependent on the center.

These changes essentially shifted the administrative structure of the Russian Federation away from its federal essence toward a unitary model. The centralization of power contributed to the intensification of authoritarianism. The abolition of local elections not only placed pressure on the majority urban population but also deprived citizens of their primary tool for influencing power—the electoral institution.

This period also saw the impact of rapid urbanization on the political system. By the mid-2010s, 74.4% of the Russian population lived in urban areas (Manukyan, 2022).

The reform process, encountering no significant resistance, led to the strengthening of the presidential institution. The reasons for the lack of resistance included the young and energetic president's high popularity (Shevtsova 2004, 50), public demand for "a strong hand" following the 1990s (Shestopal 2004, 61), the expansion of the federal budget due to national wealth, and improvements in living standards. Thus, simultaneous reforms in the electoral system, political parties, civil society organizations, and mass media fundamentally altered the political system.

Until the 2000s, the electoral institution had functioned as an important element of political culture at all levels in Russia. For example, 272 electoral blocs, federal and regional parties participated in the 1995 parliamentary elections (Shulman 2022). In subsequent election cycles, the number of political actors and electoral events declined. By 1999, only political parties could participate in elections, while public electoral blocs lost this right, reducing participants from 272 to 139 (Shulman 2023). In 2001, regional political parties were abolished; only nationwide parties were permitted.

In 2002, amendments to laws governing the registration of legal entities granted the Ministry of Justice the authority to register or deny the registration of political parties (Federal Law 2002). Later, requirements for party registration were tightened, including the expansion of member and regional structure thresholds.

Beginning in 2005, a new trend emerged in Russian domestic politics: a new law on elections to the State Duma shifted the system from mixed-member to proportional representation, and parliamentary parties began receiving federal budget funding (President of Russia, n.d.-c). The parliament would now be formed solely based on party lists. Additionally, the electoral threshold was raised from 5% to 7%. Another significant change was the removal of the "against all" option on the ballot. The minimum voter turnout requirement was eliminated, leading to a phase where elections became detached from voters. All these reforms transitioned the system from multiparty to hegemonic party rule.

Over the last 25 years, the same political parties with the same leaders have dominated parliament. Ultimately, the process enabled parliamentary parties to maintain electoral control and helped conserve the new political system. Political parties ceased to function as "elevators" for ambitious young politicians. Institutional barriers blocked pathways from municipal, regional, and parliamentary elections to federal politics. This institutionalization formed "systemic parties" and reduced political participation to a minimum. Electoral manipulation and restrictions, combined with voter apathy, eliminated the possibility for opposition forces to gain power through elections. In the 2008 elections, Putin exchanged the presidency for the prime ministership to implement term limit "reforms," increasing presidential terms from four to six years and later removing term limits altogether.

Following protests over electoral fraud in 2011, President Dmitry Medvedev promised liberalization of the electoral system. Although electoral legislation returned to the 2003 model—a mixed electoral system, lower thresholds, and eased registration rules—it failed to bring substantive change to the political system.

From Personalist Autocracy to Personalist Dictatorship

In recent years, Russia’s political regime has increasingly been described as transitioning from personalist autocracy to personalist dictatorship (Shulman n.d.). This transition is manifested in the implementation of decisions through an expanded bureaucracy—both civil and security bureaucracies—supporting a personalized government. These two wings constitute a large and growing social stratum. Since 2014, the bureaucracy, particularly in the civil and security sectors, has undergone substantial quantitative expansion.

Following the election fraud protests of 2011–2012, a notable trend emerged: the active recruitment of citizens into the state apparatus. This included the growth in the number of public servants at the federal, regional, and municipal levels, as well as increased employment in state corporations and banks.

Russia’s political system has long been marked by a high degree of statism—that is, it consists almost entirely of institutions that are part of or dependent upon the state. This trend accelerated after 2014. The expansion of the state employee base also broadened the social foundation supporting the regime. Consequently, a significant segment of the middle class in Russia today is made up of state employees and members of the law enforcement sector. These social groups, with their stable and regular income, tend to favor preserving the status quo rather than promoting change.

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, it became increasingly evident that the political system’s most visible and celebrated elements were losing their functionality and effectiveness. The sacred image of the military, intelligence services, and security apparatus—cultivated over years—began to erode. Although the propaganda machinery initially appeared effective during the early stages of the war, it gradually lost its ability to captivate the public and began to decline in popularity amid military failures.

Among the few components retaining functionality was the civilian bureaucracy, particularly financial and economic institutions such as the Central Bank, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Economic Development, and regional and municipal administrations, including governors and mayors. During this period, governors and regional administrators were granted limited decision-making autonomy, although major decisions remained centralized.

Regarding legislative activity, the most notable feature of the parliament's function has been the adoption of increasingly restrictive and repressive laws. In simple terms, this includes a wide range of prohibitions: laws introducing new criminal and administrative penalties during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020; laws banning anti-war speech, participation in protests, or any expression of dissent since 2022. These repressive laws effectively dismantled the operations of civil society and independent media. In reality, nearly all independent media outlets were either shut down or forced into exile. The same applied to civil society activists, independent experts, and analysts.

The war in Ukraine marks not only an escalation of violence but also the beginning of a new phase in Russia’s political system: a shift from personalist autocracy to personalist dictatorship. The democratic façade remains, but it serves manipulative purposes. A common approach in such regimes is not to prohibit everything outright, but to establish mechanisms to control everything that emerges. Eventually, the regime adopts these mechanisms for its own use. For instance, social media, a product of 21st-century technological advancement, was co-opted by authoritarian regimes like Russia. A recent innovation—troll factories—emerged as instinctive authoritarian responses to new challenges (Radio Svoboda 2021). The instinct for self-preservation compels these regimes to be flexible and adaptive. They may not progress well, but they adapt extremely well.

Conclusion

The research has shown that the defining characteristic of Russia’s modern political system is the dominance of an authoritarian, corrupt, and bureaucratic regime (Yavlinsky 2010). Despite the formal existence of a constitution, genuine political debate is absent, political parties are deprived of effective functioning, human rights advocacy is continuously suppressed in the non-governmental sector, the separation of powers is a fiction, courts lack independence, and elections are discredited. A major feature of this system is the profound mistrust that the population harbors toward state institutions, authorities, and law enforcement agencies.

The continued erosion of public trust in the electoral process has resulted in deep delegitimization of political authority. Emerging from oligarchic anarchy, Russia under Putin has increasingly adopted the features of a political and military imperial power.

As a model for the post-Soviet space, Russia’s political system—especially its policies toward elections, political parties, civil society, independent media, and other domains—has laid the foundation for comparative analysis and parallel observations. The oft-cited notion that authoritarian regimes learn from each other is clearly applicable. The gradual dismantling of inclusive institutions in Russia over the past 30 years and their replacement with extractive institutions have had an observable impact on other post-Soviet republics. For instance, the replication of restrictive legal changes aimed at enabling authoritarianism, or the top-down efforts to undermine electoral trust, have also been seen in Russia’s neighbors (Slivyak 2024). All of this affirms that authoritarianism is not merely a domestic concern or a national pathology—it is a threat to global peace and security.

References

Civil.ge. 2024. “То, что произойдет в Вашингтоне, имеет решающее значение.” March 30, 2024. https://civil.ge/ru/archives/589357.

Snegovaya, Maria. 2023. “Why Russia’s Democracy Never Began.” Journal of Democracy, July. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/why-russias-democracy-never-began/.

Красин, Ю. А. 2004. “Российская Демократия: коридор возможностей.” Полис, no. 6.

Ирхин, Ю. В., В. Д. Зотов, and Л. В. Зотова. 2002. Политология: Учебник. Moscow.

Радио Свобода. 2006. “Суверенная демократия Владислава Суркова сквозь призму публикаций в российской прессе.” June 30. https://www.svoboda.org/a/162957.html.

Шестопал, Елена. 2004. “Авторитарный запрос на демократию, или почему в России не растут апельсины.” Полис, no. 1: 28.

Hassner, Pierre. 2008. “Russia’s Transition to Autocracy.” Journal of Democracy, June. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Hassner-19-2.pdf.

Hassner, Pierre. 2008. “Russia’s Transition to Autocracy.” Journal of Democracy, June. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Hassner-19-2.pdf.

Karolewski, Ireneusz Pawel, and Viktoria Kaina. 2023. “Is Russia Now a Criminocracy?” LSE Blogs, October 23. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2023/10/23/is-russia-now-a-criminocracy/.

Мадьяр, Балинт. 2016. Анатомия посткоммунистического мафиозного государства на примере Венигрии. https://www.postcommunistregimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2016.05.03.pdf.

Смолин, О. Н. 2006. Политический процесс в современной России. Moscow: 203–204.

Шевцова, Л. Ф. 2004. “Смена режима или Системы?” Полис, no. 1: 47.

Shevtsova, Lilia. 2007. “Russia—Lost in Transition.” Carnegie Endowment, October 10. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2007/10/press-release-russialost-in-transition-a-new-book-by-lilia-shevtsova?lang=en.

Тиммер, Ханс. 2014. “От шоковой терапии к устойчивому развитию.” World Bank Blogs, January 23. https://blogs.worldbank.org/ru/voices/from-shock-therapy-to-sustainable-development.

Snegovaya, Maria. 2023. “Why Russia’s Democracy Never Began.” Journal of Democracy, July. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/why-russias-democracy-never-began/.

BBC. 2024. “Russia Country Profile.” March 25. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-17839672.

Урнов, М., and В. Касамара. 2005. Современная Россия: вызовы и ответы: Сборник материалов. Moscow: 26–27.

Яковлев, А. Н. 2005. “Реформация в России.” Общественные науки и современность, no. 2: 11.

Никонов, В. 2003. “Путинизм.” Современная российская политика: 29.

Шевцова, Л. Ф. 2004. “Смена режима или Системы?” Полис, no. 1: 50.

Шестопал, Елена. 2004. “Авторитарный запрос на демократию, или почему в России не растут апельсины.” Полис, no. 1: 61.

Шульман, Екатерина. 2022. “Российский правящий класс в чрезвычайном положении: функциональные и дисфункциональные элементы системы.” Доклад: Российские реалии-2022.

Радио Свобода. 2021. “Наша норма – 120 комментов в день. Жизнь кремлевского тролля.” January 24. https://www.svoboda.org/a/31065181.html.

Явлинский, Григорий. 2010. “Оценка современной политической системы России и принципы ее развития.” Яблоко, January 22. https://www.yabloko.ru/news/2010/01/22.

Радио Свобода. 2025. “Из третьего мира в первый.” March 23. https://www.svoboda.org/a/26916103.html.

Radio Free Europe. 1997. “Russia: Analysis—Bandit Capitalism Versus Capitalism With A Human Face.” March 9. https://www.rferl.org/a/1083971.html.

Немцов, Борис. 2002. “Перед Россией стоит исторический выбор: какой капитализм мы будем у себя строить?” Немцов Мост, June 14. https://nemtsov-most.org/2020/12/13/nemtsov-russia-faces-a-historic-choice-what-kind-of-capitalism-will-we-build-in-our-country/.

Конституция Российской Федерации. 2001. http://www.constitution.ru/.

GOGOV. n.d. https://gogov.ru/articles/vvp-rf.

Авторский коллектив. 2002. Типология российских регионов. https://www.iep.ru/files/text/cepra/drob.pdf.

Президент России. n.d. http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/15492.

Президент России. n.d. http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/20611.

ТАСС. 2013. “Отказ от прямых выборов глав регионов России.” October 31. https://tass.ru/info/754125.

Манукиян, Елена. 2022. “С 2010 года число горожан в России выросло.” Российская газета, May 30. https://rg.ru/2022/05/30/s-2010-goda-chislo-gorozhan-v-rossii-vyroslo.html.

Шульман, Екатерина. n.d. “Избирательная система и партии.” Открытый Университет. https://openuni.io/course/6-course-5/lesson/7/.

Российская Федерация. 2002. Федеральный Закон, March 13. http://ips.pravo.gov.ru/?docbody=&prevDoc=102038609&backlink=1&&nd=102075339.

Президент России. n.d. http://www.special.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/22402.

Сливяк, Владимир. 2024. “Зачем постсоветские страны принимают законы об иностранных агентах.” The Moscow Times, April 23. https://www.moscowtimes.ru/2024/04/23/zachem-postsovetskie-strani-prinimayut-zakoni-ob-inostrannih-agentah-a128738.