Artificial intelligence (AI) is no longer a distant prospect; it has become both a reality of our time and a defining priority for the future. From the economy to education, from culture to the defense industry, the deployment of AI technologies is increasingly shaping the path ahead. The world has entered a new era — the age of artificial intelligence — and nations are racing to adapt to its demands.

As with most major technological breakthroughs, AI has rapidly become a key front in global competition. In this context, the state of AI development in Azerbaijan offers an important lens through which to gauge the country's technological and infrastructural readiness for the challenges of the future. Given the South Caucasus’ long-standing role as a stage for geopolitical rivalry, there is little doubt that AI will soon become one of the region’s most critical arenas of competition.

This article examines the rise of AI within the South Caucasus, focusing on a comparative analysis of developments in Azerbaijan and Armenia. It considers how differences in governance, particularly Armenia’s democratic reforms versus Azerbaijan’s increasingly rigid authoritarianism — have shaped each country's trajectory in this emerging field.

Introduction

International rankings consistently show that Azerbaijan lags behind its regional peers when it comes to AI readiness, IT infrastructure, startup ecosystems, and high-tech exports. Armenia, by contrast, made remarkable progress between 2015 and 2022, overtaking Azerbaijan across most indicators.

The reasons for this shift lie primarily in economic factors linked to political differences. In Armenia, legislative reforms and targeted tax incentives between 2015 and 2022 created a nurturing environment for the IT sector. Azerbaijan, meanwhile, moved deeper into authoritarianism during the same period, eroding economic freedoms and making the country less attractive to foreign investors.

Although Azerbaijan eventually introduced tax breaks for IT in 2018 and again in 2023, the delayed timing and sluggish implementation blunted their impact. Armenia, benefiting from democratization, was able to raise its economic freedom scores and create a more favorable climate for investment — executing reforms swiftly and decisively. These contrasting dynamics help explain why Azerbaijan has steadily lost ground to Armenia in the AI race over the past decade.

AI Readiness: What Do International Indices Reveal?

The state of artificial intelligence in South Caucasus countries, as well as their ranking positions, has significantly changed over the past 10 years. According to the annual reports of the “Global Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index” published by Oxford Insights, Azerbaijan’s AI readiness level in 2019 was assessed at 5.244 points. With this score, Azerbaijan ranked 64th in the global index. Based on the same year's data, Georgia and Armenia ranked 76th (4.863 points) and 81st (4.716 points), respectively (Government Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index 2019, Trend.az 2019).

However, the next report published by the organization five years later showed that the previous results had changed significantly. According to the 2024 report, Azerbaijan dropped to 111th place globally with a score of 39.92 points. Armenia ranked 88th with 44.51 points, while Georgia placed 81st with 46.92 points (Oxford Insights 2024). Although all three countries declined in the rankings, Azerbaijan fell from first to third place within the South Caucasus.

The five-year period between the two reports indicates that there are notable differences in how South Caucasus countries approach AI technologies and that many changes have occurred across various areas during this time.

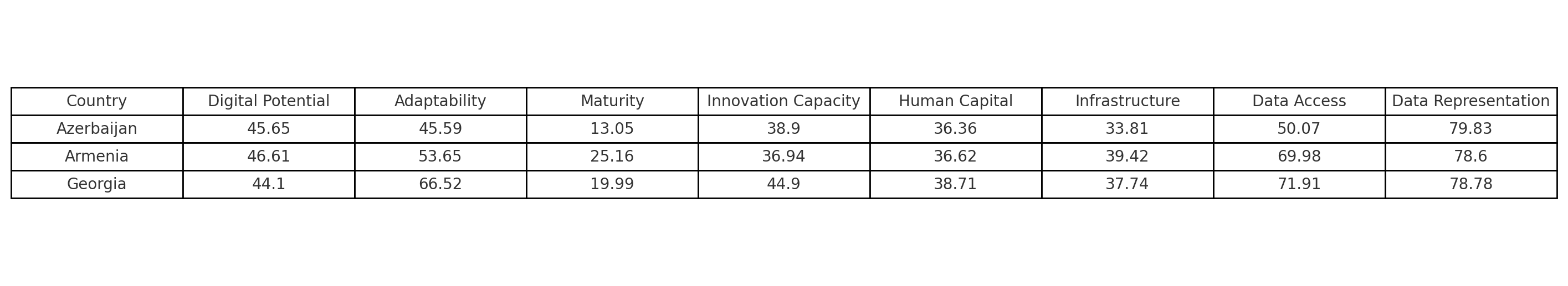

The results presented by Oxford Insights across different indicators allow us to identify the main distinctions among the region’s countries in the field of AI.

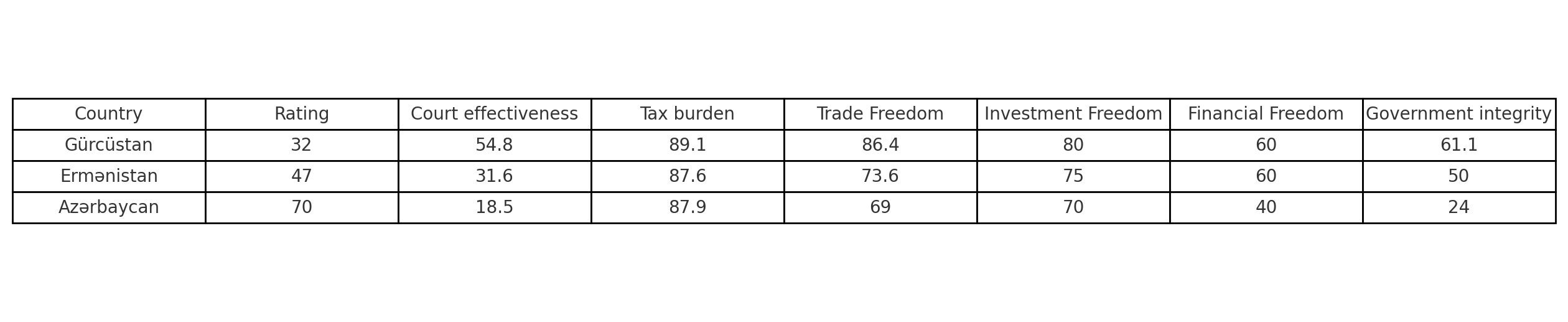

Table 1. Data from Oxford Insights' Global AI Readiness Index

Table 1. Data from Oxford Insights' Global AI Readiness Index

According to the table, the countries of the region have similar results across several indicators. However, unlike the other two regional countries, Azerbaijan significantly lags behind in the indicator of “data accessibility.” The main reason for this can be attributed to the fact that all data repositories are under direct state control, with access to these databases restricted for other actors. This situation is a result of excessively centralized authoritarian governance (Outpost Eurasia 2024). Considering that AI systems heavily rely on data processing, it is understandable that the state is the sole actor in this area in Azerbaijan.

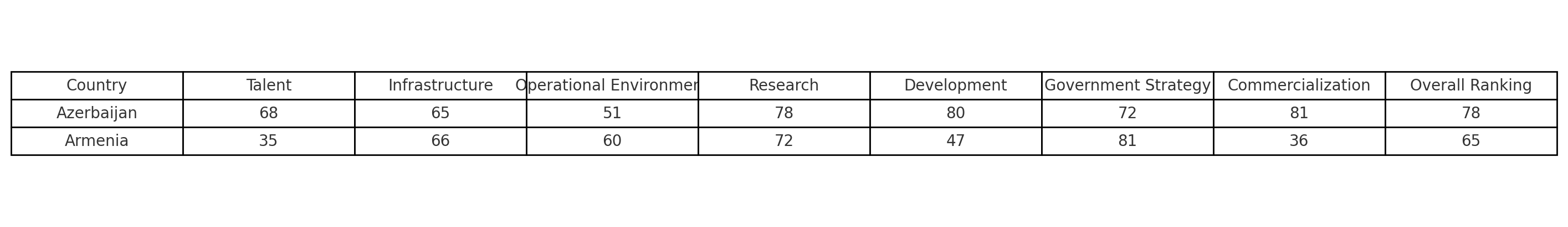

Such disparities are also clearly reflected in other similar international reports. According to the findings of another ranking in the field of artificial intelligence—the Global AI Index 2024—Azerbaijan ranks 78th globally in the index, while Armenia holds the 65th position. (Georgia was not included in the list) (Tortoise Media 2024). The table below provides a comparative overview of the specific domains assessed in the index.

Table 2. Azerbaijan and Armenia’s Scores According to the Global AI Index 2024

Table 2. Azerbaijan and Armenia’s Scores According to the Global AI Index 2024

Note: Indicators are rated on a scale from 1 (best) to 100 (worst).

According to this index, Azerbaijan scores slightly higher than Armenia in areas like operational environment and government strategy. However, Armenia holds a clear lead in talent development, research output, innovation, and commercialization — all critical pillars for building a competitive AI ecosystem.

Infrastructure and Ecosystem Comparisons

In any country, the development of artificial intelligence systems depends on the state of the necessary IT infrastructure and the startup ecosystem that builds this infrastructure, as well as key economic indicators in the high-tech sector. International indices show that Azerbaijan is not a leader among South Caucasus countries in any of these areas and even lags behind in certain aspects.

According to the Global Innovation Index published by the World Intellectual Property Organization for 2024, Azerbaijan ranks 95th out of 133 countries in terms of innovation capacity in its economy (World Intellectual Property Organization 2024). In previous years, Azerbaijan's ranking in this index was higher: the country ranked 82nd in 2020 and 80th in 2021. In contrast, Armenia and Georgia currently rank 63rd and 57th, respectively, in terms of innovation capacity. At present, the economies of these countries have greater innovation potential than that of Azerbaijan.

The global startup ecosystem research center StartupBlink annually publishes the Global Startup Ecosystem Index, which ranks 100 countries and 1,000 cities around the world based on the favorability of their environments for startup development (Startup Blink 2024). According to the 2024 data, Azerbaijan ranks 80th out of 100 countries, while Baku ranks 344th among 1,000 cities. Armenia, by comparison, ranks 57th, with the capital city Yerevan ranking 200th. Georgia and its capital Tbilisi rank 70th and 371st, respectively. As seen, Azerbaijan (Baku) lags significantly behind Armenia (Yerevan) in terms of startup ecosystem development. Although Baku ranks ahead of Tbilisi in the city index, Azerbaijan ranks behind Georgia in the national ranking.

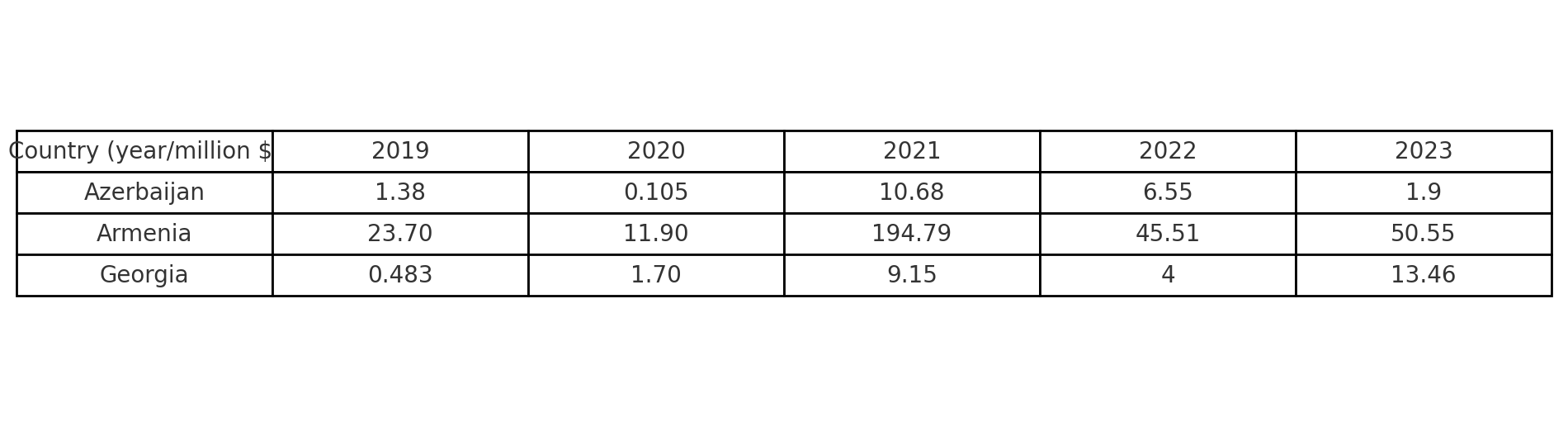

The research center also provides data on startup financing in the South Caucasus countries. The data show that Armenia surpasses the other two regional countries in terms of the volume of funding available to its startup ecosystem. Azerbaijan, on the other hand, ranks the lowest in the region for this indicator.

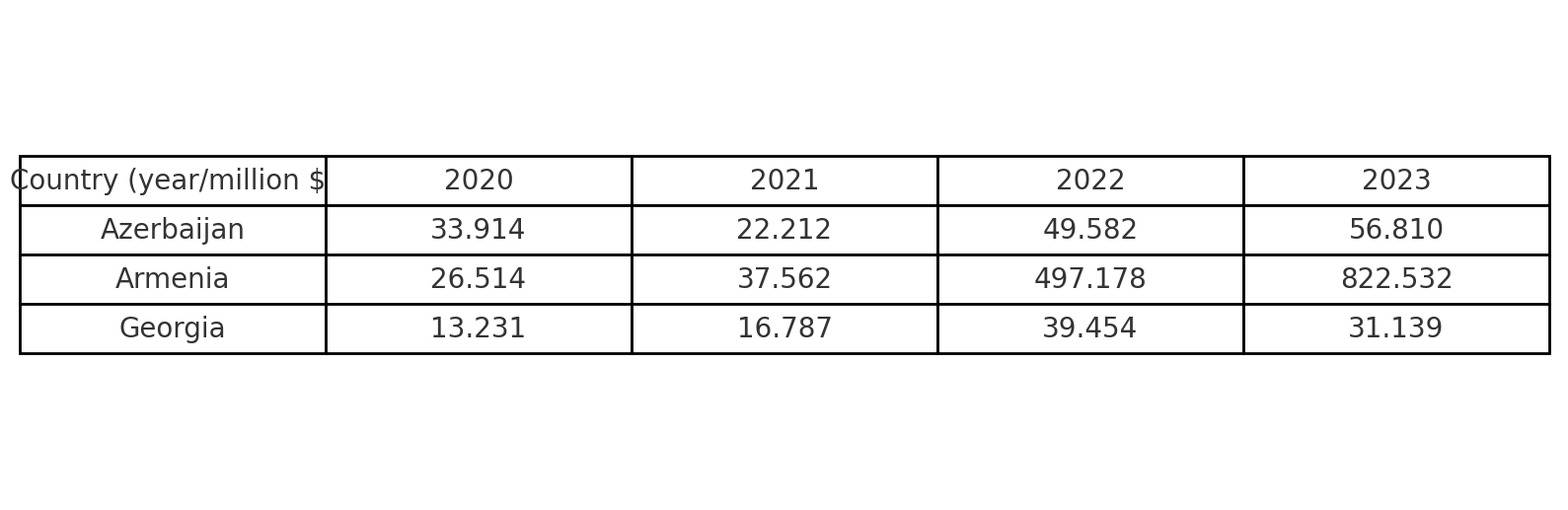

Table 3. Startup Funding Volumes of South Caucasus Countries

Table 3. Startup Funding Volumes of South Caucasus Countries

It is well known that a country’s capacity for innovation, its IT startup environment, and funding indicators are primarily linked to the level of economic freedom. This is also true for the countries of the South Caucasus. According to the Economic Freedom 2024 report published by the Heritage Foundation, the economic freedom scores of the region’s countries are as follows (Heritage Foundation 2024):

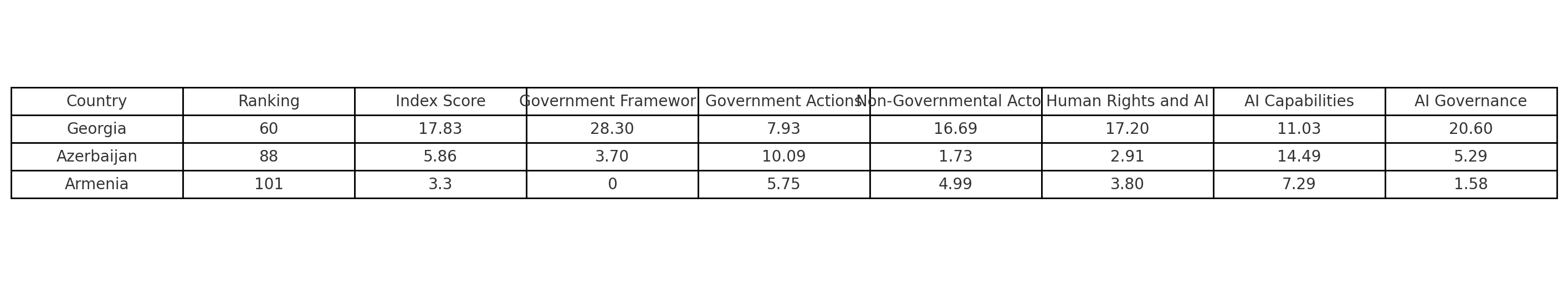

Table 4. Economic Freedom Index of South Caucasus Countries – 2024

Table 4. Economic Freedom Index of South Caucasus Countries – 2024

The table clearly shows that Azerbaijan ranks lowest in the region in terms of judicial effectiveness (18.5). Azerbaijan also holds the lowest position for other indicators such as trade freedom (69), investment freedom (70), financial freedom (40), and government integrity (24). These factors are directly linked to the characteristics of political regimes in each country, specifically to authoritarian and democratic tendencies. It is no coincidence that Armenia has surpassed Azerbaijan in these indicators based on the results achieved since 2018. The main reason why Azerbaijan scores much lower in these areas compared to Armenia and Georgia lies in this very distinction. This situation also shapes how foreign investors, companies, and experts perceive Azerbaijan.

Another important factor is the indicator related to the export potential of high-tech products. These indicators determine the volume of a country’s high-tech exports based on available resources and infrastructure. According to World Bank statistics, there is a significant gap in the high-tech export volumes among South Caucasus countries. Based on 2023 figures, Azerbaijan’s high-tech export volume amounted to 56.810 million USD (World Bank 2023). In Armenia, this figure was 822.532 million USD, while in Georgia it was 31.139 million USD (World Bank 2023).

Table 5. Export Volumes of High-Tech Products of South Caucasus Countries

Table 5. Export Volumes of High-Tech Products of South Caucasus Countries

Armenia’s performance in the export of high-tech products is similarly reflected in its figures for ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) products. According to statistical data provided by the United Nations, there are significant differences in the bilateral trade volumes of ICT products among the South Caucasus countries (UNCTAD 2024).

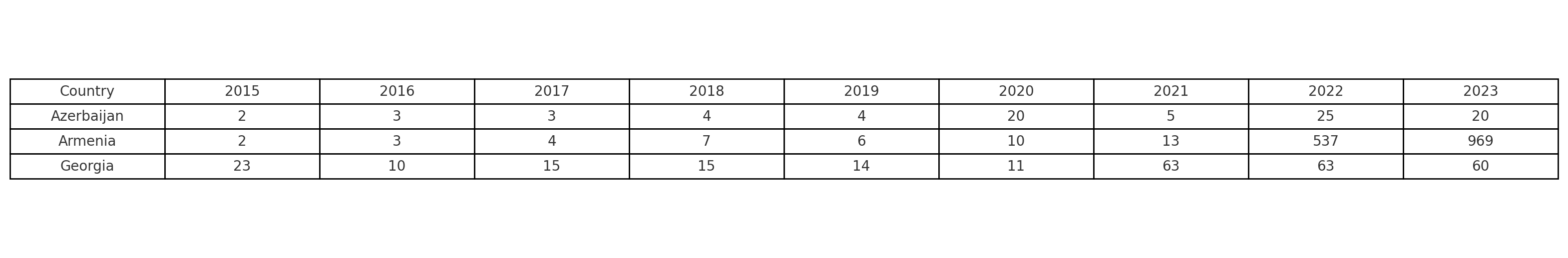

Table 6. Bilateral Trade Volumes of ICT Products in South Caucasus Countries

Table 6. Bilateral Trade Volumes of ICT Products in South Caucasus Countries

Independent regional assessments by research centers also show that Azerbaijan’s position is not particularly promising (Aratera PA 2024). Azerbaijan is considered a country with the necessary resources, high digital maturity, and adequate human capital. However, there is a noted lack of clear efforts to develop artificial intelligence, as well as a lack of specific initiatives to advance or regulate AI-based services. It is projected that Armenia will strengthen its regional leadership in computational and technological innovation, while Georgia will fall behind its neighbors.

A comparison of figures reveals that Azerbaijan and Armenia had similar performance levels until 2018, after which Armenia gradually took the lead. Particularly in 2022, Armenia’s bilateral trade volume in ICT products surged to $537 million. In contrast, Azerbaijan’s figure for the same indicator was only $25 million. Similarly, Armenia’s high-tech product exports jumped to $497 million in 2022, while Azerbaijan’s exports amounted to just $49 million.

This sharp rise in Armenia’s high-tech exports and ICT trade volume, along with the fact that Armenia has surpassed Azerbaijan in AI readiness over the past five years, is quite significant. Moreover, the fact that this leap occurred across most indicators specifically between 2015 and 2022 is particularly noteworthy. Considering that Armenia underwent democratic change in 2018, while Azerbaijan gradually slid into hard authoritarianism during the same period, it is no coincidence that these advancements coincided with shifts in political regimes.

How effective are legislative decisions?

The notable differences in infrastructure and startup ecosystems are primarily explained by the strategies implemented by the respective governments. It is no surprise that in Armenia, the development of the IT sector is largely attributed to changes in tax legislation (Shepard 2020).

In 2015, the Armenian government amended the tax legislation concerning domestic IT startups. The amendment offered full tax exemptions for the first five years for IT startups with fewer than 30 employees. Additionally, compared to the general 21% fixed income tax, employees in the IT sector started paying only 10% income tax. Before the amendment, the majority of Armenia’s IT sector revenues (51%) belonged to foreign companies. After the changes, the share of revenue between local and foreign companies became balanced, and from that point on, local companies began to dominate.

A similar policy was introduced in Azerbaijan, exempting startups from income tax. According to this policy, startups must first obtain a “Startup Certificate,” which qualifies them for a three-year income tax exemption. Although the amendment to the Tax Code was made in 2018, the Cabinet of Ministers only approved its implementation in January 2021 (Cabinet of Ministers 2021). In other words, the decision was adopted in 2018, but the issuance of the first certificates began in 2021—six years after Armenia’s corresponding policy (APA 2021).

Another legislative reform concerning the startup ecosystem in Armenia was enacted in 2022. In March of that year, the Armenian government adopted a resolution providing for the reimbursement of 50% of income tax for IT companies that employ at least 50 full-time or freelance workers (Avetisyan 2022). These changes in tax legislation quickly showed results. While the IT sector’s contribution to Armenia’s GDP was 1.5% in 2010, it rose to 7.4% in 2018. Despite a decline in the following years, the figure rose again to 4% in 2021. These tax incentives not only boosted the domestic IT sector but also created a favorable environment for IT companies relocating from abroad—especially from Russia.

After Russia launched its military aggression against Ukraine in 2022, approximately 500 Russian IT companies either relocated to Armenia or opened branches there (International Trade Administration 2023). This figure later increased to 800, and simplified customs and tax procedures were cited as the main reasons for the relocation (Azerbaijan24 2024). The absence of certain taxes and low individual income tax rates in specific areas created a favorable environment for foreign professionals in Armenia and stimulated investment inflows (Строителева 2024). By contrast, in Azerbaijan, the number of incoming IT professionals in 2022 was only 300. This number was less than 1% of the 50,000 Russian specialists who moved to Armenia during the same period (Azadlıq Radiosu 2022).

Azerbaijan’s failure to attract Russian IT professionals and companies during this critical moment made it necessary to introduce new tax incentives. Under the new exemptions announced in 2023, local and foreign entrepreneurs working in the ICT field are fully exempt from the 20% profit tax and the 14% income tax (AKTA 2023). However, this only applies to those who obtain a certificate of residency in one of the technology parks. Individuals with such certificates are exempt from income tax for up to three years if their monthly income does not exceed 8,000 AZN. If income exceeds that amount, they are required to pay 5% income tax on the surplus. Individuals who are residents of technology parks and engaged in entrepreneurial activity are exempt from income tax for 10 years (excluding tax on wages) (taxes.gov.az 2023).

So far, these new changes have mostly benefited existing startups in Azerbaijan, but have not significantly boosted the creation of new startups. Within two years after the 2023 tax incentives, the number of startups that acquired tech park residency status in Azerbaijan was 98 (most in the IT sector), while the total number of startups across the country was 157 (Innovation and Digital Development Agency 2024; startup.az 2024). In comparison, the number of startups operating in Armenia in the software development field alone exceeds 160 (Lusha.com 2024).

In Georgia, tax legislation concerning IT startups is somewhat similar to Azerbaijan’s. There, startups can obtain “Virtual Zone Entity” certificates, which allow them to benefit from various incentives, including exemption from corporate income tax. However, this approach is more favorable to foreign investors than to the local private sector (International Communication Union 2023). Foreign companies open branches in Georgia, offer competitive salaries, and attract skilled local professionals. As a result, local startups lose access to talent and fall behind in development.

These facts make it clear that introducing meaningful tax incentives and creating a favorable environment for businesses are decisive factors for the development of IT infrastructure and startup ecosystems. Unfortunately, in Azerbaijan, such incentives were implemented very late, leading to missed opportunities—such as the influx of Russian professionals in 2022.

On the other hand, the Azerbaijani case also demonstrates that legislative reforms and tax exemptions alone are not sufficient. The country’s governance system, the economic freedom environment it fosters (investment, trade, financial freedom, etc.), and the judiciary that protects that environment are essential for enabling the secure operation of foreign investments. If these elements are not ensured, tax incentives alone are not attractive enough for foreign investors and can also create operational risks for local startups.

Practical Efforts and the Current State of AI Integration

It should be noted that Azerbaijan does not lag behind Armenia in all rankings. According to the report The Global Index on Responsible AI prepared by the Global AI Governance Center, the rankings of South Caucasus countries in terms of responsible artificial intelligence between 2021 and 2023 are as follows (Global Index on Responsible AI 2024 Corrected Edition):

Table 7. Indicators of South Caucasus Countries According to “The Global Index on Responsible AI”

Table 7. Indicators of South Caucasus Countries According to “The Global Index on Responsible AI”

Note: An important consideration about this index is that the evaluation period covers the years 2021–2023, and the data was prepared based on feedback collected from survey participants.

A particularly notable point in the index data relates to the role of governments and non-state actors in the field of artificial intelligence in Armenia and Azerbaijan. While non-state actors dominate in Armenia, in Azerbaijan the government plays a direct and dominant role in AI-related activities. The evaluation of practical implementation and the current state of AI in both countries confirms this distinction.

Armenia

Strategic activities in the IT field in Armenia began to be implemented actively in the 2000s. In the early stages, branches of large companies like Synopsys Armenia played a central role in these developments. Armenia’s IT sector initially developed largely with the support of diaspora-based startups and funds abroad. Only in recent years has attention shifted toward building a vibrant and growing local startup ecosystem (ISPI 2023).

Today, the funding of Armenia’s startup ecosystem by external actors remains relevant. According to 2023 data, investments in IT startups in Armenia amounted to $216 million, 82% of which came from diaspora organizations and foreign startups. One such diaspora organization, the Foundation for Armenian Science and Technology (FAST), currently runs educational programs such as the Advance Research Grant Program and Generation AI (FAST Foundation 2023; EU4Digital 2024). These programs aim to build bridges between international scientists and local researchers, and to deliver AI education to students in 7 regions and 15 secondary schools.

Centers such as TUMO Center for Creative Technologies and Hero House, funded by foreign investment, also operate in Armenia to promote IT education among youth and teenagers (TUMO 2024; Tosunyan 2021). TUMO Armenia, which currently has 6 centers in Armenia and 9 abroad, launched a $60 million campaign to expand the number of centers to 16 between 2021 and 2026 (TUMO 2021). One of Armenia’s major achievements in 2021 was the startup Picsart surpassing a $1.5 billion valuation. Founded by Armenian specialists abroad, it became the country’s first “unicorn”—a startup reaching $1 billion in value within 10 years (Tosunyan 2021).

Despite the development of foreign investment and the local startup ecosystem in Armenia, the main shortcoming remains the lack of sufficient government support (JamNews 2025). However, steps have recently been taken in this direction. At the end of 2023, Armenia announced plans to launch its first AI supercomputing center equipped with cutting-edge technology (EU4Digital 2023). Built in partnership with NVIDIA, the center was allocated $8.5 million from the state budget. Armenia declared that this would be the first artificial intelligence computing center in the South Caucasus (Armenpress 2023). Additionally, in June 2021, it was emphasized that a forward-looking national AI strategy was needed.

Azerbaijan

In Azerbaijan, artificial intelligence technologies are primarily applied and promoted by state institutions (such as the State Examination Center, ASAN Service, etc.). This is because the databases where such systems are implemented are accessible only to government entities. Although various state institutions have made announcements regarding their use of AI across different fields, there are no substantial outcomes to show for it (Musavat 2024). Agencies like the Innovation and Digital Development Agency, Azercosmos, SOCAR, the Ministry of Digital Development and Transport, and the Central Bank have all claimed to be working on projects related to AI and supporting the development of the AI and data ecosystem. However, in practice, no significant achievements are evident.

Two state institutions are responsible for developing AI technology in Azerbaijan: “4SIM” under the Ministry of Economy and the “Azerbaijan Artificial Intelligence Laboratory” under the Ministry of Digital Development and Transport. Both institutions have announced that they will prepare AI and data strategies, but as of yet, no detailed information about such projects is available (Qafqazinfo 2024). While it is possible to access information about the “4SIM” project through its website, the official site of the Azerbaijan AI Laboratory (https://ailab.az/az/about/) is nearly inactive.

While the first year of Armenia’s AI curriculum in secondary schools will conclude by the end of 2024, there is no AI-related curriculum in Azerbaijani schools (Yeni Çağ 2024). Nonetheless, national scholarship programs in the ICT field such as Technest, as well as training courses, hackathons, and other initiatives organized by private companies, are ongoing. It is known that over 600 students received Technest scholarships in the 2021–2022 academic year, and more than 3,000 in 2022–2023.

In October 2024, it was also reported that a draft version of a national AI development strategy had been prepared in Azerbaijan (Azernews 2024). Although details of the strategy were not made public at the time, it was mentioned that one of the planned initiatives is to establish at least one innovation center focused entirely on artificial intelligence at a leading national university within the next three years. The Deputy Minister of Economy stated that the government is supporting 600 companies in the AI sector and aims to generate $40 billion in added value from AI by 2040 (Report.az 2024).

Finally, on March 19, 2025, the “Artificial Intelligence Strategy of the Republic of Azerbaijan for 2025–2028” was officially adopted (1). This strategy is a general document outlining the goals and objectives for AI development in Azerbaijan (Ibid.). While new in essence, the document maintains a traditional, state-centered approach to the AI ecosystem. The state remains the sole actor in financing mechanisms and data governance. Although public–private cooperation is mentioned, no concrete proposals are made for the development of the private sector. For business entities, tax and other incentives are merely mentioned as “planned” in a single sentence.

Given the current conditions and the lack of visible practical steps, it is difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the strategy document. However, the continued reliance on traditional approaches and the proposed vision already raise doubts about the strategy’s potential to influence regional competition meaningfully.

Conclusion

The factors mentioned above are important for understanding the fundamental differences and existing imbalances between the artificial intelligence ecosystems of Azerbaijan and Armenia. The analysis of available data shows that while AI initiatives in Azerbaijan are supported and implemented by a centralized state apparatus, in Armenia, private companies and startups play a leading role in this field. This highlights a key distinction: Azerbaijan performs better in state-supported activities, while Armenia demonstrates stronger performance when it comes to non-state (private) actors. In general, Armenia’s higher overall results suggest that a decentralized approach is more effective than a centralized, state-controlled model where everything is concentrated in a single authority.

Armenian startups operating abroad and dedicated diaspora funds play a significant role in financing Armenia’s IT sector. This has not only enabled the transfer of foreign expertise into the country but also diversified its financial and infrastructural capacities. As a result, Armenia’s IT sector has remained largely resilient to the destructive effects of domestic political upheaval (2018) and even war (2020). Azerbaijan, on the other hand, lacks such internationally recognized startups or diaspora funds. Therefore, all funding flows in a single direction—entirely from the state—and is primarily allocated to strategic areas determined by the government (especially cybersecurity). The fact that these strategic priorities change over time creates risks related to the consistency of financial inflows. Moreover, access to databases is restricted exclusively to government agencies. This creates significant obstacles for the independent development of non-state actors and blocks the emergence of a decentralized approach.

In contrast, the tax incentives implemented in Armenia have made a significant contribution to the development of the domestic startup ecosystem. These measures have been particularly beneficial in expanding the activities of non-state actors. The tax breaks have supported the growth of startups with diverse funding sources. In Azerbaijan, however, the announcement and implementation of tax incentives were significantly delayed. As a result, favorable conditions for the development of non-state actors in the country have not been fully established.

The most recently introduced tax benefits in Azerbaijan were not aimed at domestic startups, but rather at attracting foreign companies and specialists. A similar example in Georgia shows that while this approach may be successful in attracting foreign investors, it has proven ineffective in developing the local startup ecosystem or in fostering the formation of new startups. In Azerbaijan, the increasing authoritarianism of the political regime and the gradual restriction of economic freedoms raise serious questions about the effectiveness of these measures. Although the recent tax incentives, expansion of IT education, and international collaborations may generate some expectations for the future, unless they are supported by significant political reforms, their long-term success remains uncertain. Ultimately, the development of non-state actors and the expansion of public-private cooperation are closely linked to the presence of an environment of economic freedom.

Endnotes:

President of the Republic of Azerbaijan - Official Website. 2025. “Azərbaycan Respublikasının 2025–2028-ci illər üçün süni intellekt Strategiyası.” President.az, March 19, 2025. https://static.president.az/upload/Files/2025/03/19/5a0fb1886a7316cb1b95458f366c1bd6_3415396.pdf

References:

AKTA. 2023. “Ölkəmizin İKT sektoru üçün yeni güzəştlər təsdiq edilmişdir.” AKTA, January 9, 2023. https://akta.az/en/news/oelkemizin-ikt-sektoru-uecuen-yeni-guezestler-tesdiq-edilmisdir

APA. 2021. “Azərbaycanda startap şəhadətnamələrinin verilməsinə başlanılıb.” Apa.az, May 21, 2021. https://apa.az/az/xeber/sahibkarliq/azerbaycanda-startap-sehadetnamelerinin-verilmesine-baslanilib-644122

Aratera PA. 2024. “AI Strategies in Central Asia, South Caucasus & Mongolia.” Aratera PA, December 10, 2024. https://areterapa.com/insight_20241210

Armenpress. 2023. “Armenia to have first AI supercomputing center in the region.” Armenpress, November 30, 2023. https://armenpress.am/en/article/1125243

Avetisyan, Ani. 2022. “Big Talk, Fast Growth But Still Early Stage: Armenia’s Tech Industry.” EVN Report, April 28, 2022. https://evnreport.com/creative-tech/big-talk-fast-growth-but-still-early-stage-armenias-tech-industry/

AzadlıqRadiosu. 2022. “Azərbaycan IT sektorunda ciddi vergi güzəştlərinə hazırlaşır.” AzadlıqRadiosu, December 23, 2022. https://www.azadliq.org/a/informasiya-texnologiyalari-guzest/32190349.html

Azerbaijan24. 2024. “Russian companies embark on massive expansion to ‘friendly’ countries.” Azerbaijan24.com, February 27, 2024. https://www.azerbaycan24.com/en/russian-companies-embark-on-massive-expansion-to-friendly-countries/

Azernews. 2024. “Azerbaijan announces draft strategy for artificial intelligence development.” Azernews.az, October 10, 2024. https://www.azernews.az/business/232395.html

Trend.az. 2019. “Azerbaijan leading in Global Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index in region.” En.trend.az, September 24, 2019. https://en.trend.az/business/it/3123204.html

EU4Digital. 2023. “Armenia’s first AI supercomputing centre expected to boost technological advances.” EU4Digital, December 4, 2023. https://eufordigital.eu/armenias-first-ai-supercomputing-centre-expected-to-boost-technological-advances/

EU4Digital. 2024. “Armenia’s ‘Generation AI’ programme marks a successful first year.” EU4Digital, July 9, 2024. https://eufordigital.eu/armenias-generation-ai-programme-marks-a-successful-first-year/

Fast Foundation. 2023. “Advance Armenia Global Campaign.” Fast Foundation, 2023. https://fast.foundation/en/program/6786/2023/general-information

“Global Index on Responsible AI 2024 Corrected Edition.” 2024. https://girai-report-2024-corrected-edition.tiiny.site/.

“Government Artificial Intelligence Readiness Index 2019.” 2019. Accessed May 2, 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/ai_readiness_index_2019__0.pdf.

Heritage Foundation. 2024. “Index of Economic Freedom.” Heritage Foundation, 2024. https://www.heritage.org/index/pages/report

International Telecommunication Union. 2023. “Digital innovation profile: Georgia.” International Telecommunication Union, 2023. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/inno/D-INNO-PROFILE.GEORGIA-2023-PDF-E.pdf

International Trade Administration. 2023. “Information and Telecommunication Technology.” International Trade Administration, November 29, 2023. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/armenia-information-and-telecommunication-technology

ISPI. 2023. “How Russian Migration Fuels Armenia’s IT Sector Growth.” ISPI, November 6, 2023. https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/how-russian-migration-fuels-armenias-it-sector-growth-151311

JamNews. 2025. “Armenia faces choice: lead or follow others – IT specialist.” JamNews, January 27, 2025. https://jam-news.net/armenia-faces-choice-lead-from-front-or-follow-others-it-specialist/

Lusha.com. 2024. “Top Software development companies in Armenia.” Lusha.com, 2024. https://www.lusha.com/company-search/software-development/021d3a8f4f/armenia/219/

Meljumyan, Ani. 2022. “Armenia’s tech industry: Promise fulfilled?” Eurasianet, February 16, 2022. https://eurasianet.org/armenias-tech-industry-promise-fulfilled

Musavat. 2024. “Azərbaycanda süni intellekt həlli hazırlamaq mümkünsüzdür, çünki... – DETALLAR.” Musavat.ru, April 23, 2024. https://musavat.ru/news/azerbaycanda-suni-intellekt-helli-hazirlamaq-mumkunsuzdur-cunki-detallar_1063418.html

Nazirlər Kabineti. 2021. “Startapın müəyyən olunması meyarları”nın təsdiq edilməsi barədə.” E-Qanun, January 29, 2021. https://e-qanun.az/framework/46782

Outpost Eurasia. 2024. “CCA: AI Ambitions and Realities.” Outpost Eurasia, August 9, 2024. https://outposteurasia.com/insights/tpost/p4zfdtx341-cca-ai-ambitions-and-realities

Oxford Insight. 2024. “Government AI Readiness Index 2024.” Oxford Insight, 2024. https://oxfordinsights.com/ai-readiness/ai-readiness-index/

Qafqazinfo.az. 2024. “Hansı qurumlar süni intellektdən istifadə edir?” Qafqazinfo.az, February 13, 2024. https://qafqazinfo.az/news/detail/hansi-qurumlar-suni-intellektden-istifade-edir-427028

Report.az. 2024. “Azerbaijan aims for $40 billion in added value in AI by 2040.” Report.az, December 6, 2024. https://report.az/en/ict/azerbaijan-aims-for-40-billion-in-added-value-in-ai-by-2040/

Schjelderup, Leigha. 2022. “The (Unrealized) Imperative of AI in Armenia.” EVN Report, August 18, 2022. https://evnreport.com/creative-tech/the-unrealized-imperative-of-ai-in-armenia/

Shepard, Wade. 2020. “Welcome To The World’s Next Tech Hub: Armenia.” Forbes, February 2, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2020/01/31/welcome-to-the-worlds-next-tech-hub-armenia/

Startup Blink. 2024. “Startup Ecosystem Report 2024.” Startup Blink, 2024. https://www.startupblink.com/startupecosystemreport

startup.az. 2024. “Startaplar.” startup.az, 2024. https://www.startup.az/startup.html

Taxes.gov.az. 2023. “Texnologiya parklarının rezidentləri.” Taxes.gov.az, 2023. https://www.taxes.gov.az/uploads/2023/bukletler/3.6.pdf

Technest.az. 2024. “Technest təqaüd proqramı.” Technest.az, 2024. https://technest.idda.az/az

Tortoise Media. 2024. “The Global AI Index.” Tortoise Media, 2024. https://www.tortoisemedia.com/intelligence/global-ai

Tosunyan, Syuzan. 2021. “Unicorns Spotted in Armenia.” EVN Report, October 4, 2021. https://evnreport.com/creative-tech/unicorns-spotted-in-armenia-2/

Tumo 2021. “TUMO Announces $60 Million ‘TUMO Armenia’ Campaign To Extend Its Learning Network Nationwide.” Tumo.org, September 18, 2021. https://tumo.org/tumo-announces-60-million-campaign/

Tumo 2024. “What is Tumo?” Tumo.org, 2024. https://tumo.org/whatistumo/

UNCTAD. 2024. “Bilateral trade flows by ICT goods categories, annual.” UNCTAD, November 24, 2024. https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.IctGoodsValue

World Bank. 2023. “High-technology exports.” World Bank, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/TX.VAL.TECH.CD

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). 2024. “Azerbaijan ranking in the Global Innovation Index 2024.” World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), 2024. https://www.wipo.int/gii-ranking/en/azerbaijan

Xeberler.az. 2025. “Osman Gündüz: Ölkədə süni intellekt sahəsində vəziyyət necədir?” Xeberler.az, January 17, 2025. https://xeberler.az/new/details/osman-gunduz:-olkede-suni-intellekt-sahesinde-veziyyet-necedir--33820.htm

Yeni Çağ. 2024. “Süni intellektin imkanlarından orta və ali məktəblərdə necə istifadə olunur?” Yeni Çağ, September 16, 2024. https://yenicag.az/suni-intellektin-imkanlarindan-orta-ve-ali-mekteblerde-nece-istifade-olunur/embed

İnnovasiya və Rəqəmsəl İnkişaf Agentliyi. 2024. “Texnopark rezidentlərinin siyahısı.” İnnovasiya və Rəqəmsəl İnkişaf Agentliyi, 2024. https://www.idda.az/texnopark/az/

Строителева, Мария. 2024. “Все те же юрлица: бизнес из РФ открыл 11 тыс. филиалов в дружественных странах.” Известия, February 26, 2024. https://iz.ru/1654509/mariia-stroiteleva/vse-te-zhe-iurlitca-biznes-iz-rf-otkryl-11-tys-filialov-v-druzhestvennykh-stranakh