It is precisely in this sense that the concept of “cultural lustration” remains relevant today. In the post-Soviet space, including in Azerbaijan, the influence of former authoritarian regimes lives on not only within state governance structures, but also in public consciousness, collective memory, rituals, and everyday behavioral norms. This means that without dismantling the symbols and cultural codes of the former regime, formal political change will not be sufficient to democratize the deep structures of society.

In transitional literature, the term “lustration” (from the Latin lustratio – purification ritual) is generally explained as the process of removing from state positions persons who collaborated with the former authoritarian regime (David, 2011). After 1989, lustration laws implemented in Central and Eastern Europe primarily targeted former employees of security agencies, high-ranking party officials, and individuals involved in political repression. This was mainly a legal-institutional mechanism: lists, archives, trials, or dismissal from office.

However, this classical approach did not touch upon the cultural codes, symbolic capital, and constructions of collective memory of the former regime. Yet the durability of authoritarianism rests not only on its administrative apparatus but also on the cultural norms, rituals, and ideological architecture it has created. For this reason, in modern transitional literature, the concept of “cultural lustration” is becoming increasingly relevant.

Cultural lustration is the deconstruction of the symbols, discourses, rituals, and behavioral reflexes formed by the former authoritarian regime. This process is not merely a personnel change but a rewriting of the ideological codes of collective memory (Stan, 2009).

The Theoretical Framework of Cultural Lustration

Political lustration answers the question “who”: Who collaborated with the former regime? Is their participation in governance dangerous?

Cultural lustration, however, focuses on the questions “what” and “why”: What symbols did the former regime present as “normal”? Why do these symbols still live in the public and cultural life of our time?

German cultural memory researcher Aleida Assmann, when explaining memory politics, emphasizes that the past is preserved in society in two main forms: material memory and symbolic memory (Assmann, 2011). These two forms complement each other and together constitute the cultural pillars of authoritarian regimes’ longevity.

Material Memory

Material memory is built upon the physical traces of the past. It includes:

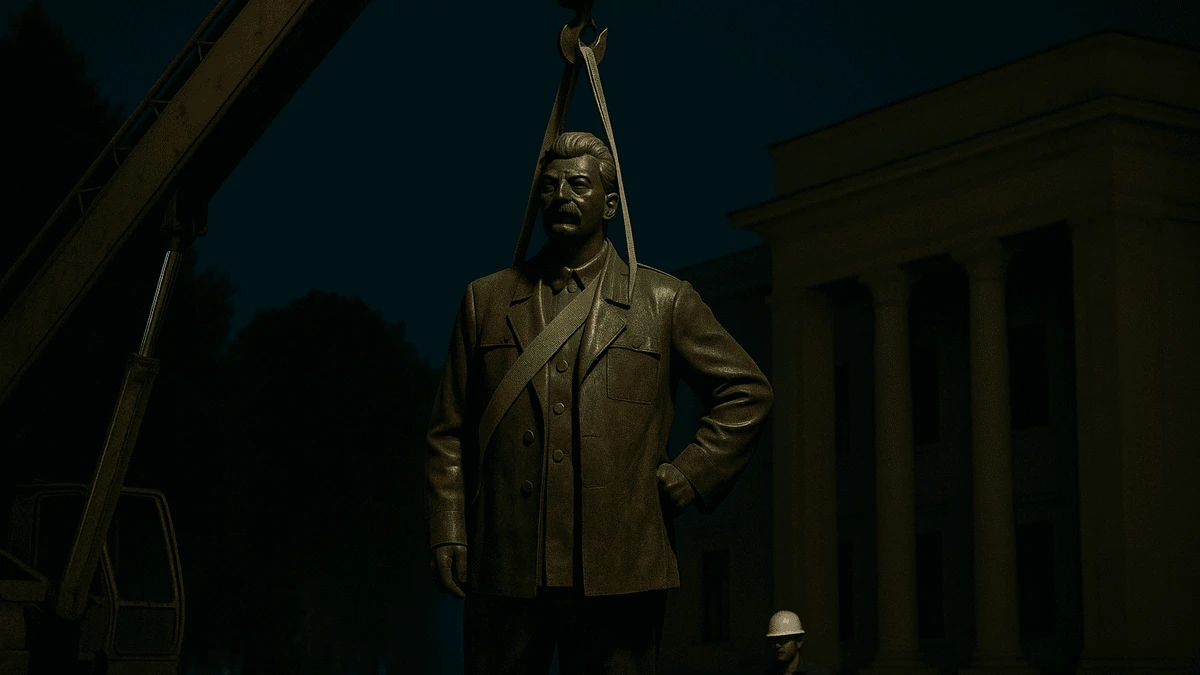

- Statues and monuments – monumental depictions of authoritarian leaders, military heroes, and ideological symbols;

- Street and city names – turning everyday spaces into a “memory map” through ideological coding;

- Official holidays and state ceremonies – reinforcing certain historical events and symbols annually through state-organized rituals.

These elements ensure ideological control over memory in public spaces. During the Soviet era, toponyms like “Lenin Square” in every city were part of both everyday life and collective identity. Changing material memory (for example, removing statues, renaming streets) is the first and most visible stage of cultural lustration.

Symbolic Memory

Symbolic memory relates less to physical objects and more to ideas, rituals, and behavioral codes. It includes:

- National hero images – leader and personality cults promoted by the authoritarian regime;

- “Historical consciousness” narratives – presenting the past in line with state ideology (e.g., the “savior leader” story);

- Collective rituals – parades, anniversaries, military demonstrations organized at the state level.

Symbolic memory is less visible but more enduring. It survives through intergenerational transmission and becomes a “normalized ideological reflex.” For example, in the post-Soviet space, the “strong leader” archetype remains an important pillar of political legitimacy. This has become a cultural behavioral code.

Memory Hegemony

According to Antonio Gramsci’s concept of “memory hegemony,” political power is built not only through force but also through control over culture and memory. For authoritarian regimes, memory politics is a system of ideological norms reproduced to reinforce their legitimacy. These norms live in history books, school lessons, holiday programs, and even in popular culture.

Cultural lustration targets both forms of memory — material and symbolic. It is not enough to dismantle statues and rename streets. The main task is the deconstruction of symbolic memory, meaning:

- Placing the “savior leader” myth in its historical context and subjecting it to criticism;

- Replacing the “heroic” narratives of the authoritarian era with a pluralistic historical perspective;

- Reformatting official rituals and holidays in line with democratic values.

This process must be carried out through state decisions, education, art, media, and civic initiatives.

Comparative Examples

- Germany – Denazification policy was not limited to banning Nazi symbols; it also deconstructed Nazi ideological codes through school curricula, the film industry, literature, and theater.

- Poland – Alongside renaming communist-era streets, the memory of the “Solidarność” movement was presented as the main national narrative; new national holidays were created.

- Baltic states – In addition to dismantling monuments dedicated to the Soviet army, the symbols of the independence era were made dominant in the cultural space.

- Strategic Goals of Cultural Lustration

- Decoding the mythological past – Authoritarian regimes often base their legitimacy on a “heroic history”: “the leader’s salvation,” “ensuring stability,” “victory over a foreign enemy.” Cultural lustration dismantles these myths through historical criticism and empirical facts (Verdery, 1999).

- Forming behavioral reflexes compatible with democracy – In post-authoritarian societies, belief in a “strong leader” and the expectation of “top-down decisions” persist. Cultural lustration aims to replace these reflexes with a pluralistic and participatory culture.

- Destroying the legitimacy base of authoritarian cultural heritage – If authoritarian cultural heritage remains unquestioned, it becomes a “hidden pillar” beneath democratic institutions.

- Building a new inclusive cultural identity – This process is not only about dismantling the past but also about creating a new, open, and pluralistic national memory.

Tools of Cultural Lustration

- Criticism of official history policy – “Official narratives” constructed by the state must be questioned in academic and public debates. This is not only the work of historians but also the responsibility of journalists, artists, and civic activists.

- Reflective content in artistic creation – Literature, cinema, and theater should convey the traumas and paradoxes of the authoritarian period through the language of art.

- Spatial and symbolic policy – Reassessing monuments, street names, and state rituals. West Germany’s denazification policy in the 1950s–60s is an important example in this field.

- Ethical accountability in the cultural elite – Public accountability of those in media, academia, and the arts who collaborated with the authoritarian regime.

The Cultural Stage of Democratic Transition

Cultural lustration is a process of moral and cultural transformation that complements the legal-institutional stage of political transition. If this stage is not implemented, the symbolic capital of the former authoritarian regime — ideological narratives, constructs of national heroism, state rituals, and politics of historical memory — can be easily appropriated by new political elites. This paves the way for “post-authoritarian authoritarianism,” where democratic institutions formally exist but governance principles remain essentially authoritarian.

Democracy is not only a model of state governance but also a matter of memory and culture.

References:

RFE/RL, 2010. Stalin Statue Removed In Georgian Hometown. https://www.rferl.org/a/Stalin_Statue_Removed_In_Georgian_Home_Town/2082559.html

David, Roman. Lustration and Transitional Justice: Personnel Systems in the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299550761_Lustration_and_Transitional_Justice

Stan, Lavinia, ed. Transitional Justice in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Routledge, 2009. https://www.routledge.com/Transitional-Justice-in-Eastern-Europe-and-the-former-Soviet-Union-Reckoning-with-the-communist-past/Stan/p/book/9780415590419?srsltid=AfmBOooWIwQx8BtZO2m1L61RISBU3IeihMxMciHNlZYpbqrr5E9RPaZq

Assmann, Aleida. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives. Cambridge University Press, 2011. https://assets.cambridge.org/97805211/65877/frontmatter/9780521165877_frontmatter.pdf

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers, 1971. https://ia600506.us.archive.org/19/items/AntonioGramsciSelectionsFromThePrisonNotebooks/Antonio-Gramsci-Selections-from-the-Prison-Notebooks.pdf

Verdery, Katherine. The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change. Columbia University Press, 1999. https://cup.columbia.edu/book/the-political-lives-of-dead-bodies/9780231112314/

Bernhard, Michael, and Jan Kubik, eds. Twenty Years After Communism: The Politics of Memory and Commemoration. Oxford University Press, 2014. https://academic.oup.com/book/5239