(This article was prepared within the framework of KHAR Center’s research project “Authoritarian Regimes and Transregional Mechanisms of Influence”.)

Introduction

Until the end of the 20th century, Turkey’s foreign policy was primarily directed at preserving the achievements of the Treaty of Lausanne in the face of serious threats from major powers. For this reason, for a long period, Turkey acted as a country favoring the status quo, with its relations with neighboring states shaped mainly by the stance it took in broader geopolitical confrontations (Zürcher 2017).

However, following the end of the Cold War, Turkey’s growing economic, military, and diplomatic power changed the situation. Ankara began to direct its foreign policy not only toward maintaining the existing order but also toward reshaping the regional order in line with its expanding capacity for influence (Öniş & Yılmaz 2009). The nature of these efforts, and how they were perceived by neighboring states, would in the future become one of the key factors shaping Turkey’s relations with the United States and Europe. Regardless of which political force is in power, Turkey’s new dynamism will continue to remain a source of tension. Yet, if properly managed, this dynamism may also prevent a permanent rupture between Turkey and the West (Marc Pierini 2020).

At present, Turkey’s relationship with its Western allies is in a state of “growing tension,” while Ankara seeks to project itself on the international stage as a revisionist power. This is reflected in its regional policy, which, alongside periodic rapprochements, also openly reveals sharp conflicts that emerge from time to time (Larrabee & Lesser 2003). For this reason, it has become increasingly important to carefully follow Ankara’s zigzagging steps and to understand their long-term implications.

The purpose of this KHAR Center analysis is to examine Turkey’s global political ambitions and its strategic autonomy game in foreign policy.

The central question of this paper is the extent to which Turkey’s political-economic and ideological resources align—or fail to align—with its global political ambitions.

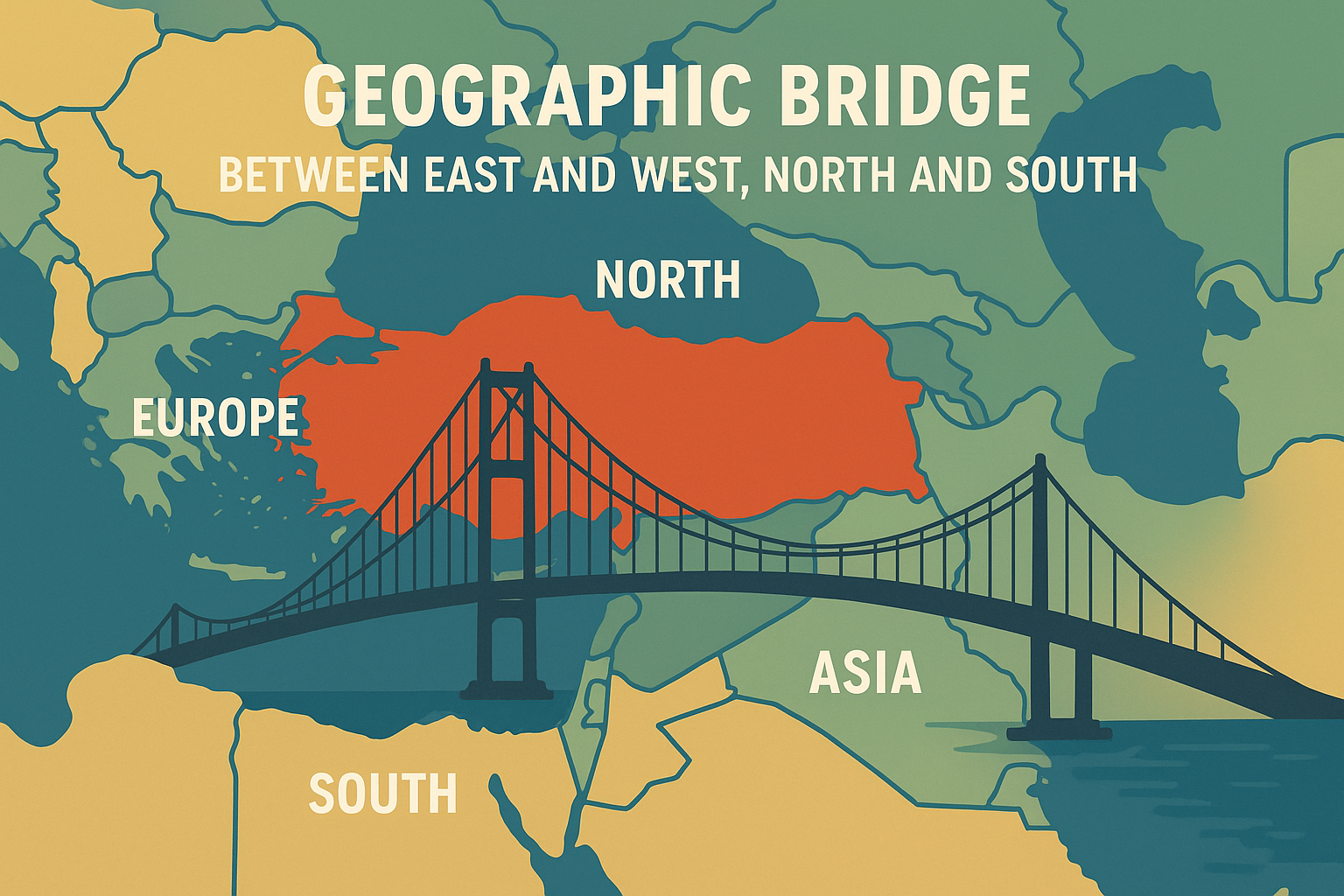

Geographic Bridge: Between East and West, North and South

Turkey is geopolitically connected to many regions: it shares a border with the European Union; across the Black Sea lie Ukraine and Russia; to its northeast is the South Caucasus, and it borders the Middle East; through the Mediterranean, it is also connected to North Africa.

This geographical position has become a defining feature of Turkey’s foreign policy. That feature has become especially pronounced during the rule of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Having come to power in 2002, Erdoğan still remains in office today as president. Although he has been accused of suppressing the opposition through the courts and dispersing protests inside the country, in foreign policy he pursues an active and ambitious line (Tugal 2016a).

Turkey’s military base in Somalia, where Turkish soldiers provide training, is the country’s largest overseas military facility. This is just one example of Ankara’s growing global ambitions.

With its geographical location, Turkey stands at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and Africa. This uniqueness brings the country both advantages and challenges. Its position provides access to three continents, but at the same time pulls it into the potential and hot conflicts of the Caucasus, the Middle East, and the Black Sea (Philip Robins 2004).

The Strategic Autonomy Game: Ideological and Political Reference Points

Strategic autonomy in Turkey’s foreign policy largely entails a multi-vector strategy. Over the years, this approach manifested itself in different policies, while academically it took shape in former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu’s Strategic Depth doctrine (Davutoğlu, A. 2001a). Global developments and the fractures in the traditional international security system have turned this approach into one of the key components of Erdoğan’s slogan, the “Turkish Century.” Whether in Turkey’s role as a NATO member, its relations with the US and the EU, or its economic partnerships with China and Russia—together, these all illustrate the broad scope of Turkey’s quest for strategic autonomy (Altunişik, M. 2020). This quest unfolded gradually, advancing in parallel with authoritarianization on international, regional, and domestic levels.

In the 21st century, the shift toward multipolarity accelerated with the political and economic rise of the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), making the global balance of power more uncertain and complex. The 2007–2008 financial crisis exposed the inefficiency of Western economic institutions, paving the way for new institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Moreover, the repeated violations of international rules and human rights norms, met with either inadequate or selective responses by the US and EU, prompted other states to prioritize their own interests over collective security (Amitav Acharya, 2017).

From Ankara’s perspective, at the core of this global disorder lies the weakening role of the US and EU in certain regions. America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, undertaken on its own initiative, was a sign of this decline. The US retreat and its pivot toward Asia was another indication of the changing global configuration and the “power vacuum” it created. Against such a backdrop, Turkish policymakers no longer feel as tied to the Western agenda led by the United States. Despite being a NATO member, Turkey continues to expand its partnerships outside the West, including with Russia and China. This reevaluation of values also takes place against the backdrop of accumulated disappointments in bilateral relations with the US and EU (Senem Aydın-Düzgit, Mustafa Kutlay & E. Fuat Keyman, 2025).

Disagreements with Washington became particularly sharp after the US turned to cooperation with the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) in the fight against ISIS. This, combined with America’s disregard for Ankara’s concerns regarding the Gülen movement after the 2016 coup attempt, deepened frustration within Turkey’s leadership and public. According to the German Marshall Fund’s Transatlantic Trends 2022 survey, 67% of Turkish citizens believed that the US played a negative role internationally. The failure of Turkey’s EU accession process and the growing tensions with the EU further fueled anti-Western sentiment. By treating Turkey as a “privileged partner,” the EU effectively refused to regard it as an “internal member” of Europe. The turning point in bilateral relations was Cyprus’s accession to the EU and the failure to resolve the island’s political division. Together, these political problems have, in recent years, reduced EU–Turkey relations to a transactional framework of cooperation (GMF 2022).

In fact, the roots of anti-Western sentiment in Turkey stretch back much further. Without dwelling on the matter too long, it is worth noting that the first signs of tension in US–Turkey relations appeared in the 1960s. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, President Kennedy reached an agreement with Soviet leader Khrushchev to withdraw the nuclear-armed Jupiter missiles stationed in Turkey without even informing Ankara. This came as a cold shock. Two years later, President Johnson wrote a letter to Prime Minister İnönü expressing disapproval of Turkey’s preparations for an intervention in Cyprus, forbidding the use of American weapons in such an operation. He even warned that if the intervention provoked a Soviet attack on Turkey, NATO would not intervene. The “Johnson Letter” dealt a long-lasting blow to bilateral relations. The anti-American sentiment that emerged spilled over into skepticism toward Turkey’s European integration movement and eventually morphed into general anti-Westernism (William Hale, 2013a). For this reason, neither the White House’s behavior during the 2016 coup attempt nor the further rise of anti-Americanism in Turkey came as much of a surprise.

Historically, as a NATO member and EU candidate country, Turkey sought to align itself with the Western bloc. Now, however, by embracing a policy of strategic autonomy, it openly wavers between global powers. In today’s world—where the traditional international security system is collapsing and a “post-Western” order looms—Turkey seeks to position itself as a leading member of one of the new centers of power (Mustafa Kutlay, Ziya Öniş, 2021).

It should be noted that the instability created by multipolarity strengthens security-oriented thinking. The specific strategic outlook that shapes Turkey’s behavior in the international system stems mainly from a security discourse. This is linked to the century-old fear of “partition from outside”—the so-called “Sevres Syndrome.”

The Arab uprisings, fragmented regional states, and civil wars have left proxy conflicts along Turkey’s borders, intensifying this fear. Disputes over maritime zones, exclusive economic areas, and gas resources in the Eastern Mediterranean have reinforced a similar sense of isolation. Turkey’s 2019 maritime boundary agreement with Libya’s Government of National Accord cannot be explained without taking into account Ankara’s perception of being “diplomatically encircled” after being excluded from the Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum (Aaron Stein, 2022a).

Thus, the essence of strategic autonomy is not irredentist or expansionist motives but rather a compelled reaction to regional and global processes that alter the status quo.

In domestic politics, however, the strategic autonomy narrative has turned into a useful tool for rallying voters “around the flag.” Erdoğan’s anti-Western rhetoric resonates with both Eurasianists and Islamists. Even the leftist electorate, who have adopted a Western lifestyle, with their own traditional anti-Western narrative, become objects of Erdoğan’s political tactics in this context.

His criticism of the West for double standards, as well as his accusations that Israel is committing “genocide” in its war against Hamas, demonstrate this. Such political rhetoric is part of Erdoğan’s attempt to present himself as the leader of the global Islamic ummah. Accusing the EU of Islamophobia, strengthening ties with the Muslim Brotherhood in the post–Arab Spring Middle East, and sending development aid and military support to Muslim-majority African countries like Somalia are visible manifestations of this claim (Ali Balcı, 2024).

Another line complementing the strategic autonomy narrative is populist techno-nationalist rhetoric. During the 2023 presidential election campaign, Erdoğan frequently highlighted the country’s achievements in the defense industry. As part of the campaign, he personally attended unveiling ceremonies for projects such as the KAAN national fighter jet, Turkey’s largest warship TCG Anadolu, and the Kızılelma unmanned fighter jet (Can Kasapoğlu and Sine Özkaraşahin, 2024).

By presenting his tough maneuvers in foreign policy as expressions of national identity and interests, Erdoğan managed to stigmatize the domestic opposition as “anti-national.” Interestingly, Turkey’s political opposition has proved incapable of crafting an effective response to this framework. Often, they too have become captives of the security-oriented foreign policy narrative (Tugal, 2016b). In truth, public sentiment drives them in that direction. Naturally, the factor of strengthening the country’s deterrent power and developing its defense industry cannot be ignored. Yet this factor must be assessed alongside the growth of the ruling family’s economic-political monopoly. The entire defense industry, with its flagship “Bayraktar” company, essentially forms the basis of Erdoğan’s family business. Mega-projects carried out through initiatives like Teknofests also serve to politically elevate family member Selçuk Bayraktar (Aaron Stein, 2022b).

Power Resources

A population of 85 million, a young demographic, a strong industrial base, and NATO’s second-largest army after the United States already grant Turkey the status of a regional power. With more than 350,000 active soldiers, Turkey is a serious player in both Europe and the Middle East (IISS, 2023).

Until recently, Turkey primarily relied on trade, diplomacy, and its critical geographic location between Europe and the Middle East to demonstrate its strength. However, against the backdrop of a decade of instability triggered by the Arab Spring uprisings beginning in 2011, Ankara shifted toward a hard power approach—both to protect itself from threats and to pursue its ambitions of becoming a global power.

Turkey’s complex geographical position—situated between Europe and Asia, between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean—places it at the heart of multiple geographic, political, and cultural geostrategic environments at once. This reality strongly influences its domestic, foreign, and defense policies and makes Ankara extremely sensitive to emerging security threats in its neighborhood (Fulya Hisarlıoğlu, 2022).

Traditionally, Turkey’s geography has been perceived as a dividend, a bridge between East and West. But a less noted aspect is that this geography also confronts Turkey with unique challenges and threats. This has placed the issues of territorial integrity, security, and national interests at the very center of Turkish political, security, and defense thinking. These challenges have pushed Turkey toward adopting a “strong state model” and increasing its reliance on hard power (William Hale, 2013b).

International discourse on Turkey often ignores these factors. As a result, beyond answering the questions “what is Ankara doing?” or “what is it trying to do?,” the most essential questions—“why is it doing this?” and “what is its ultimate goal?”—remain unanswered.

From Soft Power to Hard Power

In the first decade of the 21st century, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) managed to chart a middle course, distancing itself both from the radical secularism enforced by military rule and from rigid religious dogmatism. Its attempts to reconcile democracy, secularism, and Islam drew international attention to Turkey as a rising country with a modern, liberal economy. During that period, Turkey built significant soft power potential and presented itself as a “model” (Ihsan Yilmaz & Syaza Shukri, 2024).

This soft power rested on three pillars:

- Experience of democratization and reforms;

- Growing trade and sustained economic growth;

- Visionary, attractive, and active foreign policy (zero problems with neighbors, high-level political dialogue, economic integration and interdependence, security for all, multicultural coexistence) (Davutoğlu, 2001b).

As a result, Turkey was able to build and assert its soft power both in the region and beyond. This power was used to inspire regional peoples and became one of the underlying factors behind the uprisings that began in 2010. However, these revolutions simultaneously generated long-term and unpredictable security challenges for Turkey.

When the Syrian revolution began on March 11, 2011, Turkey’s then–foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu spent months trying to persuade Syrian president Bashar al-Assad to stop the unjustified and excessive use of force against peaceful protesters and to begin reforms, in exchange for Turkey’s support. But Assad leaned toward Iran, prompting intensive debate among Ankara’s decision-makers over the question: “What should be the next step?” The prevailing view was that Turkey, relying on its considerable reserves of soft power, could still influence events beyond its borders and reshape the region in a way that would promote democracy and genuine stability—outcomes that would ultimately serve Ankara’s interests.

But the crisis that followed the downing of a Russian Su-24 fighter jet by a Turkish F-16 after it violated Turkish airspace in 2015 turned into a confrontation of wills and hard power. While NATO issued statements of support for Ankara along with calls to de-escalate, Turkey perceived these as signs of alliance inaction and abandonment by Western partners. This convinced some Turkish officials that over-reliance on soft power and foreign partners weakened Turkey’s security positions and limited its proactive policy options. It became clear that full trust in defensive soft power and in others’ willingness to cooperate regionally was a costly mistake (Aaron Stein, 2022c). The shifting dynamics required Ankara to reconsider how to secure its borders, manage the refugee crisis, and influence the political future of the region.

This situation encouraged Turkey to pursue its nearby interests with more overt displays of power. Despite Iran’s and Russia’s defense of Assad, Turkey supported the rebels against the regime in Syria. With Iran’s influence waning and Russia preoccupied with the war in Ukraine, Turkey was able, through the rebel forces it backed, to launch an offensive that ultimately toppled Assad’s regime by the end of 2024.

The weakening of Iran’s influence in the region, due in part to US and Israeli strategies, also added a layer of complexity to Turkey’s role in shaping the new Middle Eastern order. Turkey does not want to see its occasional rival Iran collapse before Israel, because maintaining a balance between Iran and Israel is in Ankara’s strategic interest.

Although the emerging regional landscape seems to open up new opportunities, Israel’s attempts to limit Turkey’s influence in Syria and its war with Iran cast doubt on Turkey’s ability to preserve its hard-won advantage.

On top of this, the main factor constraining Turkey’s global ambitions is its deepening economic crisis. The lira’s collapse to the brink of bankruptcy and record-level inflation leave Ankara unable to finance large-scale plans abroad. As a result, Turkey has turned to cooperation with the wealthy Gulf countries—Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar—for financial support (Şevket Pamuk, 2018).

Middle East and Africa Track

Close military cooperation with Qatar allows Turkey to expand its influence despite financial constraints. In Africa, when Erdoğan first came to power there were embassies in only 12 countries; now that number exceeds 40. This indicates Ankara’s strategy to increase its influence on the continent (BusinessDiplomacy, 2021).

First, consulates and embassies are opened; then Turkish Airlines begins flying to those destinations; trade and investment expand; humanitarian aid flows to those countries; and infrastructure and logistics development follows. Turkish companies have specialized in building airports and other infrastructure projects across Africa. At present, Turkey is building mosques across the continent and, in parallel with the expansion of its defense industry, is transferring more military and security components to Africa.

In 2011, when Somalia was suffering from famine and civil war, Erdoğan became the first non-African leader to visit the country in the past 20 years (Anadolu Agency, 2016). In 2017, Turkey opened a military base (Camp TurkSOM) in the capital, Mogadishu. The base, said to host 2,000 Turkish soldiers, trains Somali troops (dbpedia, 2017). Turkey has also undertaken to help build Somalia’s navy and protect its coastline.

Turkey and Somalia lie on opposite ends of the main trade route stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean via the Red Sea and the Suez Canal. Right in the middle of this route, off the coast of Sudan, Turkey has leased Suakin Island. Once an important port city, the abandoned island is where Ankara now plans to build new maritime infrastructure. Turkey has also begun exploring for oil and gas in Somali waters. A core part of Turkey’s offer to African states is military equipment. Turkish-made weapons, such as the Bayraktar, sell well in Africa. Turkish defense products are cheaper, and Turkey imposes fewer conditions on arms exports than many other countries—for example, the United States. Turkey’s diplomatic rhetoric also appeals to African partners: Ankara emphasizes its lack of a colonial past and its respect for African choices in solving the continent’s problems.

Turkey’s Return to Central Asia and the Caucasus

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Turkey—whose application for membership in the European Union had just been rejected—experienced a sense of euphoria. The emergence of five Turkic-origin states in the Caucasus and Central Asia opened an alternative to European integration: Turkey could turn east and attempt to build a new confederation of Turkic states. The idea was greeted with great enthusiasm, but soon appeared unworkable for a number of reasons. First, the Turkic peoples of the former USSR had only just freed themselves from one master and had no need for a new one. In addition, Turkey faced domestic problems— the rising PKK insurgency in the southeast, a weak economy accompanied by runaway inflation, and the ascent of Islamist politics that alarmed the secular leaders of Central Asia and Azerbaijan.

Over the next two decades, Central Asia and the Caucasus did not occupy a major place in Turkish foreign policy. In the 2000s, economic realities forced Turkey to reorient toward the EU. After consolidating power, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the AKP government plunged south into the tangled politics of the Middle East, keeping Turkey occupied for more than a decade. However, following the 2016 coup attempt, the combination of domestic and external shocks led to a nationalist-oriented restructuring at home, which in turn revived interest in the Turkic states of Central Asia and the Caucasus.

In the South Caucasus, Turkey has a special partnership with Azerbaijan. In Central Asia, it is building closer ties with Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, continuing to increase its influence. Economic and cultural ties are expanding. In these ties, for example, the religious factor occupies a special place through the financing of mosques (Bruce Pannier, 2024).

All of these republics—whose populations are predominantly of Turkic origin and speak Turkic languages—were once part of the Soviet Union and had close ties with Russia. But this is changing. Russia’s being bogged down in the quagmire of Ukraine allows Turkey to be more active in both regions (Hoover Press, 2023).

In this context, Turkey and Azerbaijan are particularly close. The slogans “one nation, two states” and “brother country” have become common refrains for the political elites of both countries. Moreover, the fact that these are not empty slogans became clear to everyone during the most recent (2020) war with Armenia. Turkish weapons and support played a major role in Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenia (hecaliforniacourier, 2024).

Cooperation between the two countries has also expanded significantly in the economic sphere. For example, after the 44-day war, nearly all of the multi-billion-dollar infrastructure projects in Karabakh were awarded without tender to Turkish companies close to Erdoğan. Likewise, investments by Azerbaijani companies linked to the Aliyev family in Turkey are increasing by the day. Turkey has also participated in selling Russian gas to Europe under the label of Azerbaijani gas.

As a result, Turkey has certain advantages and limitations in both regions. For instance, in the South Caucasus—which directly borders Turkey—Ankara can readily become the dominant power and undermine Russia’s traditional position. While this process has already begun in some respects, even though at the most recent Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting (September 1, 2025) the Turkish president met with the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia and tried to project the image of a guarantor of possible peace between the two countries, Ankara’s stance ultimately depends mainly on its relations with Baku. For one reason or another, any cooling between the two authoritarian leaders of Turkey and Azerbaijan could seriously damage Turkey’s influence in the South Caucasus.

Turkey has also deepened its ties with Georgia and, particularly in the defense industry, has developed trilateral Turkey–Azerbaijan–Georgia relations. Nevertheless, the Georgian government is increasingly falling under Russia’s influence, and Ankara’s emphasis on ethno-linguistic issues could strengthen the hand of certain circles in Georgia that view Turkey’s intentions with suspicion.

Moreover, normalization of Turkey–Armenia relations is of decisive importance for expanding Turkey’s influence. This, in turn, depends on the signing of a peace agreement between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Although certain positive steps have been taken in this direction, a final outcome still seems distant.

In Central Asia, Turkey’s influence is unlikely to be as strong as in the South Caucasus. However, the development of robust military ties between Turkey and the leading states of Central Asia is entirely realistic. It is also expected that Ankara will become a key supplier of arms for the region. This, in turn, could be a factor that changes the regional balance of power. Yet Ankara clearly understands that China’s influence in Central Asia is growing to a decisive degree (KHAR Center, August 2025). Russia, meanwhile, is historically entrenched there. Once the war with Ukraine ends, it may return and alter the regional balance once again.

Conclusion

Turkey’s experience shows that even states with the status of middle powers can expand their spheres of influence by managing competition. Each time Ankara steps back and deploys a rhetoric of cooperation, development, and joint action, new doors open to regional opportunities. This expanding role can also be seen as one reason why Western allies turn a blind eye to Turkey’s democratic backsliding.

However, Turkey still depends on the West economically and militarily, and in its pursuit of strategic autonomy it cannot go too far and end up isolated. Although it is a NATO member, Ankara is often perceived as an unreliable partner. This makes Turkey’s foreign policy resemble “navigation during a transition period”: we speak of a multipolar world, but the full picture of geopolitics is not yet clear. In present realities there is a fine line between cooperation and competition, and Turkey has so far managed to maintain this balance (Hürcan Aslı Aksoy, June 2025).

While Ankara’s ability to shape regional balances is a significant achievement, it is not sufficient to make it a global power. Turkey’s claims to global power cannot be realized without economic stability, institutional robustness, and domestic democratic legitimacy. In other words, even as Ankara increases its regional clout, there are doubts that it possesses sufficient resources to project its influence to the global level.

These doubts raise the question of whether some degree of dialogue and coordination between Western states and Turkey is possible regarding the Caucasus and Central Asia. Perhaps in these areas, where interests overlap, dialogue is precisely what Turkey–West relations need. Ongoing disagreements on Middle Eastern issues fuel mutual dissatisfaction and worsen relations among officials on both sides. By contrast, dialogue on Central Asia and the Caucasus—where interests converge—could have a positive effect on Turkey’s relations with Western states. In the near future, both regions will continue to occupy a special place in Turkey’s foreign policy. If the West can prepare itself for this, then after a presumed new security settlement between the West and Russia—which could push Central Asia and the South Caucasus down to a “third-world” level in security terms, as during the Cold War—it might be possible to protect these regions from Russian expansion.

References:

Zürcher 2017. Turkey: A Modern History. https://www.perlego.com/book/917902/turkey-a-modern-history-pdf

Öniş & Yılmaz 2009. Between Europeanization and Euro-Asianism: Foreign Policy Activism in Turkey during the AKP Era. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/248953895_Between_Europeanization_and_Euro-Asianism_Foreign_Policy_Activism_in_Turkey_during_the_AKP_Era

Marc Pierini, 2020. Turkey’s Labyrinthine Relationship With the West: Seeking a Way Forward. https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2020/09/turkeys-labyrinthine-relationship-with-the-west-seeking-a-way-forward?lang=en

Larrabee & Lesser 2003.Turkish Foreign Policy in an Age of Uncertainty. https://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1612.html

Tugal, 2016a. The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism. https://www.versobooks.com/products/188-the-fall-of-the-turkish-model?srsltid=AfmBOorok_8BdDIdH2pQ_D0I7ImvwxT_Fe1PUO0Qw1zX1PMR3K9Vlte1

Philip Robins,2004. Turkish Foreign Policy Since the Cold War. https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/olj/si/si_3_4/si_3_4_sab01.pdf

Davutoğlu, A. 2001a. Strategic Depth: Türkiye's International Position. https://www.kureyayinlari.com/Kitap/10/stratejik_derinlik

Altunişik, M. 2020. Turkey’s foreign policy toward Israel: co-existing of ideology and pragmatism in the age of global and regional shifts. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41311-024-00619-z

Amitav Acharya, 2017. The End of American World Order. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342345330_The_End_of_American_World_Order_Ch1

Senem Aydın-Düzgit, Mustafa Kutlay & E. Fuat Keyman , 2025. Strategic autonomy in Turkish foreign policy in an age of multipolarity: lineages and contradictions of an idea.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41311-024-00638-w

GMF, 2022.Transatlantic Trends. https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/2022-09/Transatlantic%20Trends%202022.pdf

William Hale, 2013a. Turkish Foreign Policy since 1774. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347495045_Turkish_Foreign_Policy_since_1774

Mustafa Kutlay , Ziya Öniş ,2021.Turkish foreign policy in a post-western order: strategic autonomy or new forms of dependence? https://academic.oup.com/ia/article/97/4/1085/6314232

Aaron Stein,2021a. Turkey’s Zero Sum Foreign Policy. https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/turkeys-zero-sum-foreign-policy/

Ali Balcı, 2024. Determinants of Türkiye’s Relations with Africa. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/4230331

Can Kasapoğlu and Sine Özkaraşahin, 2024. Turkey’s emerging and disruptive technologies capacity and NATO: Defense policy, prospects, and limitations. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/turkeys-emerging-and-disruptive-technologies-capacity-and-nato-defense-policy-prospects-and-limitations/

Tugal, 2016b. The Fall of the Turkish Model: How the Arab Uprisings Brought Down Islamic Liberalism. https://www.versobooks.com/products/188-the-fall-of-the-turkish-model?srsltid=AfmBOorok_8BdDIdH2pQ_D0I7ImvwxT_Fe1PUO0Qw1zX1PMR3K9Vlte1

Aaron Stein,2021b. Turkey’s Zero Sum Foreign Policy. https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/turkeys-zero-sum-foreign-policy/

IISS 2023. The Military Balance 2023. https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance/the-military-balance-2023/

Fulya Hisarlıoğlu ,2022. A Critical Geopolitical Reading of Turkish Foreign Policy. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-97637-8_3

William Hale, 2013b. Turkish Foreign Policy since 1774. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347495045_Turkish_Foreign_Policy_since_1774

Ihsan Yilmaz & Syaza Shukri, 2024. Islamist Populist AKP and Turkey’s Shift Towards Authoritarianism. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-97-4343-8_8

Davutoğlu, A. 2001b. Strategic Depth: Türkiye's International Position. https://www.kureyayinlari.com/Kitap/10/stratejik_derinlik

Aaron Stein,2021c. Turkey’s Zero Sum Foreign Policy. https://warontherocks.com/2022/12/turkeys-zero-sum-foreign-policy/

Şevket Pamuk,2018. Economic Development of Turkey since 1820. P. 177-178 https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691166377/uneven-centuries?srsltid=AfmBOoob6HUh3o7ceaGwAC1OiVWUQ34izoYtlpnGPECncsTk8KG0UoNs

Business Diplomacy, 2021. The Number Of Embassies Of Turkey In Africa Will Increase To 44. https://businessdiplomacy.net/6825-2/

Anadolu ajansı, 2016. Turkish President Erdogan visits in Somalia. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/energy/archive/turkish-president-erdogan-visits-in-somalia/6439

dbpedia, 2017. Camp TURKSOM Somali: Xerada TURKSOM, Turkish: Somali Türk Görev Kuvveti Komutanlığı. https://dbpedia.org/page/Camp_TURKSOM

hoover press, 2023. Central Asia and the War in Ukraine. https://www.hoover.org/research/central-asia-and-war-ukraine

hecaliforniacourier, 2024. https://www.thecaliforniacourier.com/turkey-officially-challenges-azerbaijan-monopoly-on-victory-in-44-day-karabakh-war/

Bruce Pannier, 2024.The Rise Of The Organization Of Turkic Statesca. https://about.rferl.org/article/the-rise-of-the-organization-of-turkic-states/

Khar Center, avqust 2025. The China Factor: Exporting Authoritarian Dependency from Central Asia to the South Caucasus. https://kharcenter.com/en/researches/the-china-factor-exporting-authoritarian-dependency-from-central-asia-to-the-south-caucasus

Hürcan Aslı Aksoy, June 2025. The Future of NATO: Strategic Ambiguity: Turkey’s Complex Role in NATO’s Evolution. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/international/22147.pdf