Introduction

This analysis scrutinizes the instrumentalization of collective memory for the purpose of homogenizing and dominating internal politics, i.e., silencing critics of such homogenization in the context of Russia’s authoritarian realm.

Current authoritarian regimes and illiberal democracies often utilize anti-colonial rhetoric to advance their geopolitical agenda without presenting a clear view of how they will approach human harm occurring within their sovereign territory. This is particularly concerning, as persisting high-level corruption and structural inequalities frequently result in harm to vulnerable groups. (Young 2024) Furthermore, the regular crackdown on functional human rights defense groups and media, which are implicitly portrayed by Sergey Narishkin, director of the Foreign Intelligence Service of the Russian Federation, during his visit to Azerbaijan, as malicious “extra-systemic opposition forces” and “international terrorist organizations” used by foreign intelligence services to the end of destabilization of socio-political circumstances, will eventually leave vulnerable groups without precise and tangible defense and support in cases of Russia and Azerbaijan if it has not done it yet. (Ingvarsson and Kalinina 2024; Human Rights Watch 2024; “Служба Внешней Разведки Российской Федерации.” 2024)

In this analysis, Khar Center aims to demonstrate how narratives derived from historical writings that shape collective memory are used to demonize critics by Russia’s authoritarian rulers, portraying them exclusively as the political agents of the Collective West.

By “Collective memory”, we mean the characterization of a shared past by a specific social group that experienced identical past events and/or practices. (Wertsch, Roediger, and Zerr 2022, 120).

Theoretical Foundations of Collective Memory and Russia’s Schematic Narrative Template

It would be pertinent to examine Maurice Halbwachs’ writings primarily to understand the foundations of collective memory studies comprehensively. Halbwachs's scholarship, as a Durkheimian intellectual, philosopher, and sociologist, is widely recognized as the foundational systematization of the concept of collective memory as a theory. To understand the maxim that Halbwachs puts forward, individual memory is immanent to the meaning attached to it by social milieu, I propose to peruse his work called Les Cadres Sociaux De La Mémoire. (Halbwachs 1925, 53) He charmingly describes perception shifts in perceiving past events using the example of our relationship with the beloved book of our childhood. We often feel excited and indeed want to re-experience those same memories while reading a favorite book of our childhood. But when we re-read it, we experience it differently as the book may seem unfamiliar, we may think some parts are missing or are additional… (Halbwachs 1925, 46) This shift in perception occurs since memories always change their functionalities in connection with specific time and social surroundings, which is called localization of memories (Halbwachs 1925, 52-53). Thus, the meanings of memories are dynamic, not static. (Halbwachs 1925, 52-53)

In contemporary times, researchers of the particular field bring up the interdisciplinarity of collective memory studies, proclaiming that it exceeds the limits of the discipline of psychology whilst utilizing collective memory studies based on Halbwachs’ approach to explain elusive social phenomena such as the rise of nationalism and/or the emergence of various social movements. James V. Wertsch, psychologist and sociocultural anthropologist, is the modern researcher of collective memory, who analyzed it from a sociocultural standpoint and eventually came up with groundbreaking research outcomes. Elaborating on Bruner’s, Lev Vygotsky’s, and Mikhail Bakhtin’s views Wertsch sketches out how “textual resources” in the form of narratives organize a collective memory under the influence of nation-states since nation-states possess utmost regulatory power to monitor and control production, and to substantial extent, consumption of “textual resources”. (Wertsch 2008, 122) Subsequently, based on Wertsch’s findings, one can empirically observe how nation-states are employing collective memory to mobilize masses using narratives. Wertsch categorizes narrative analysis into two divisions: (i) specific narratives and (ii) schematic narrative templates. (Wertsch 2008, 122-123)

While analysis of specific narratives deals with one concrete episode of the past, a schematic narrative template assists us in comprehending general patterns of the tractation of past events. (Wertsch 2008, 123) Borrowing the concept of “recurrent constants” from Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp and the concept of “schemata” from psychologist Bartlett, James V. Wertsch defined and theorized schematic narrative template as a methodological measurement tool of textualizing collective memory, which categorizes the organization of national meta-narratives into evolutionary stages. (Wertsch 2008, 124) Applying these theoretical underpinnings, Wertsch defined the Russian schematic narrative template following the discourse analysis of historic writings and empirical analysis via interviews and named it “the expulsion of foreign enemies” template. This template is as follows:

- “Initial situation”: Russia is peaceful and does not interfere with others.

- Trouble emerges: A Foreign enemy maliciously attacks Russia.

- Losing almost everything: The Enemy attempts to vanish Russia as a civilization.

- Despite all the difficulties, acting alone, Russia wins with exceptional heroism and expels foreign enemies.

(Wertsch 2008, 131)

The author acknowledges that the template may indicate a connection to the actual experience of the members of the Russian narrative tradition; however, it should be considered that the particular template is hegemonically used in Russia to understand and interpret past events. (Wertsch 2008, 132)

Since these schematic narrative templates expound the entangled social phenomena into very simple moral binaries, political elites can easily manipulate them to make distinctions such as oppressors/victims to speculate the public opinion. Based on this assumption, this analysis argues that besides setting a political agenda, collective memory can be specifically used to discredit critics of the authoritarian regime while shadowing misdoings of the state, as it can create ethical blind spots to conceal the harm.

Discrediting Narratives as Tools of Justification

Maintaining the mass consumption of discrediting narratives through controlled media, educational institutions, and other means in an authoritarian context, incumbent officeholders can put dealing with harm on the back burner by attacking critics of and those who are casting light on human rights violations, including human rights defense groups and free media. Jelena Subotić argues that the narration of past events strongly conditions political actions, as she analyzed such a tendency in the cases of Serbia and Croatia in her book, “Stories States Tell: Identity, Narrative and Human Rights in the Balkans”. (Subotić 2013, 307-308) According to Subotić, narratives designate the policies related to the future and the current times as “just,” putting them in controversy with the “unjust” past. Subsequently, “national security cultures”, which are structured by myth-making about historical enemies and past tragedies, derive from these controversies. (Subotić 2013, 308)

Thus, given the underpinnings mentioned earlier, we posit that justification for harm and attacking critics may take place through various scenarios or mechanisms. On the one hand, governing authorities may employ victimhood narratives. Being a victim makes it feasible to take “preemptive” measures against anything portrayed as hazardous. Historically, empires, which are the predecessors of the Collective West states, and which presumably conveyed colonial institutional memory to them, are perpetrators of colonialist crimes and atrocities. So, given this, it is viable to disseminate discrediting narratives about civil society and free media, positioning them in the “unjust” side of “just/unjust” controversy or moral binary, regardless of the nature of their activities, underlining their connections with so-generalized “Western institutions”.

On the other hand, authorities may depict the dissemination of such discrediting narratives as morally important to persuade implementers to continue spreading these narratives for the sake of common interests. In this situation, one can presume that it should not be that difficult to demonize dissents, journalists, human rights activists, and the rest who stand by freedoms and human dignity. To this end, as described by Ulus Baker, a Turkish Cypriot sociologist, rulership may obsolete the “thinking” function for the masses by utilizing “the techniques of repetition and persistence”. (Baker 1995) The technique of repetition assists in occupying minds with tedious repeats, while the technique of persistence streams the same information in various ways, such as emotional, political, formalistic, etc., through the mobilization of different mediatic channels. (Baker 1995)

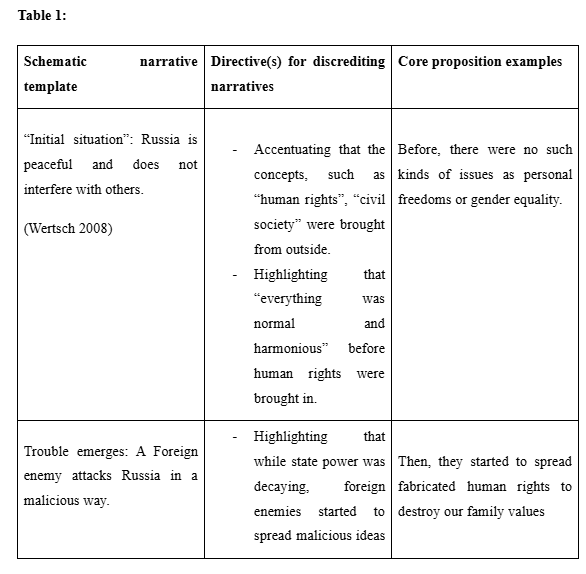

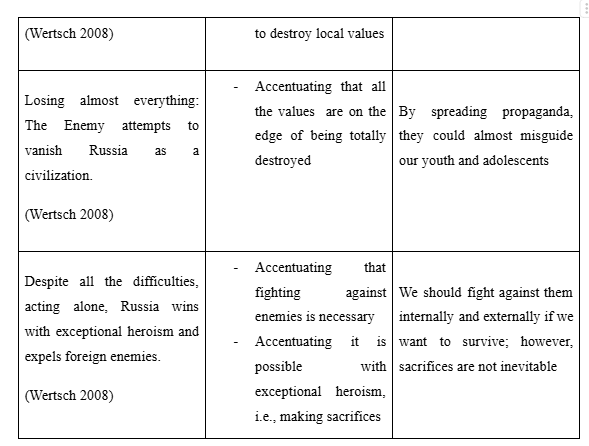

Subsequently, besides defining it, if we desire to see a more complex structure of such delegitimization, we may approach James V. Wertsch’s concept of the schematic narrative template. Building upon the hermeneutical conclusions drawn above, Wertsch’s findings may facilitate comprehending the structural evolutionary stages of discrediting narratives against critics. For instance, the table below (Table 1) illustrates how authorities may use the schematic narrative template of the members of the Russian narrative tradition to formulate conceptual directives for discrediting narratives with rough applicable narrative examples. Respectively in the first, second, and third columns of the table (Table 1), stages of the schematic narrative template, directives for discrediting narratives, and core proposition examples are correspondingly positioned with conceptual linkages.

Table 1:

As seen above (Table 1), discrediting narratives may have strong relations with schematic narrative templates. However, it has to be mentioned that narratives related to not one but several stages may be actual and spread at the same time. So, they are not mutually exclusive.

Deliberative Shifts and Constructing Counter-Narratives

I contend that the sections written above could, at least, convey the importance of taking into consideration the collective memory in assessing how authoritarian regimes and illiberal democracies attempt to shape public opinion. Seemingly, they were successful in numerous cases. We will now discuss how defining and systematizing the narratives per respective schematic narrative templates and making strategies out of it may eventually contribute to avoiding being entrapped by discursive traps of authoritarian and illiberal regimes.

Based on the theoretical underpinnings of the relation between schematic narrative templates and discrediting narratives, the counter-strategy can be developed in three stages. First, one should define the schematic narrative template characteristic of a certain social group. Second, deliberative shifts based on human rights principles should be conducted on the defined schematic narrative template. Third, counter-narratives should be constructed for each phase of the schematic narrative template. A detailed explanation of this three-staged strategy-making is given below:

- Defining the schematic narrative template:

Defining a certain schematic narrative template of any mneomonic-social group is an elusive process. Backing the research practice of collective memory scholars so far, it would be pertinent to mention that this process involves a comprehensive discourse analysis of historic writings, such as religious manuscripts, legends, as well as, a comprehensive empirical analysis of how members of narrative tradition narrate past events, which possess high political importance. Thus, a schematic narrative template can be defined by combining discourse and empirical analyses.

- Deliberative shifts:

The process of defining possible directives for discrediting narratives, as illustrated in Table 1, and counter-directives to them, is the process of “deliberative shifts”. However, it should be acknowledged that this process is likely also elusive, as it requires careful consideration of the schematic narrative template alongside ontological and methodological discussions on the localization of human rights principles in the context of dominating narrative conjecture. Putting it in simple words for replicability, one should fill in Table 1, defining the schematic narrative template alongside corresponding directives for discrediting narratives and core propositions in order to implement the process of “deliberative shift”. This process should be as comprehensive as possible, as a type of mapping.

- Constructing counter-narratives:

After finalizing the stages mentioned earlier, one can move on to constructing counter-narratives against discrediting narratives around human rights by proposing counter-core propositions. So, based on these counter-core propositions, it would be possible to construct counter-narratives that are not “out of the mind map” of a certain mnemonic-social group.

Conclusion

In sum, this analysis depicts the methods of weaponization of collective memory in a structured way, showing how it can be systematically manipulated to demonize and “other”ize internal critics of the authoritarian regime. The piece you have read discussed the theoretical interpretations on how Russia instrumentalizes the collective memory to dominate public opinion. The analysis presents an extraordinary approach, investigating the role of collective memory policies in strengthening the authoritarian rule internally. Based on the actuality and availability of the literature, we have attempted to conduct such an analysis in the evolving authoritarian context of Russia.

James V. Wertsch’s theory of schematic narrative template presents groundbreaking insights not only into understanding the emergence of nationalist social movements as originally intended but also is arguably substantially functional in comprehending how discrediting narratives may enforce an authoritarian regime to homogenize and dominate the country.

Furthermore, this conceptual analysis brought up a new notion called “deliberative shifts” for strategy-making against the misuse of collective memory. Also, this analysis may initiate further comparative or empirical inquiries into the relationship between schematic narrative templates or meta-narratives of the past and legitimization of silencing alternatives in different political contexts and landscapes.

References:

- Baker, Ulus. 1995. “Medyaya Nasıl Direnilir - Ulus Baker | Birikim Sayı 68–69.” Birikim Dergisi. https://birikimdergisi.com/dergiler/birikim/1/sayi-68-69-aralik-ocak-1995/2268/medyaya-nasil-direnilir/4590.

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1925. Les Cadres Sociaux de la Mémoire. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. https://classiques.uqam.ca/classiques/Halbwachs_maurice/cadres_soc_memoire/cadres_sociaux_memoire.pdf.

- Human Rights Watch. 2024. “Azerbaijan: Vicious Assault on Government Critics.” October 8, 2024. https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/10/08/azerbaijan-vicious-assault-government-critics.

- Ingvarsson, Stefan, and Ekaterina Kalinina. 2024. “Is Civil Society Still Alive in Russia?” SCEEUS, September 20, 2024. https://sceeus.se/en/publications/is-civil-society-still-alive-in-russia/.

- Subotić, Jelena. 2013. Stories States Tell: Identity, Narrative, and Human Rights in the Balkans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5612/slavicreview.72.2.0306.

- Wertsch, James V. 2008. “The Narrative Organization of Collective Memory.” Ethos 36 (1): 120–135. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20486564?seq=3.

- Wertsch, James V., Henry L. Roediger, and Cristopher L. Zerr. 2022. Collective Memory: Conceptual Foundations and Group Formation. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003205135.

- Young, Benjamin R. 2024. “Russia Is Riding an Anti-Colonial Wave Across Africa.” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/09/russia-is-riding-an-anti-colonial-wave-across-africa.html.

9. Sluzhba Vneshney Razvedki Rossiyskoy Federatsii. 2024. “V Baku S Ofitsial’nym Vizitom.” http://svr.gov.ru/smi/2024/10/v-baku-s-ofitsialnym-vizitom.htm.