Abstract

The emergence of digital information technologies once raised illusions about the revival of a global wave of democratization. The onset of the Arab Spring in 2011 created the impression that information technologies could become a powerful tool for democratic uprisings against authoritarian governments. However, the opposite happened. Digital technologies—enabling social media, AI-based surveillance systems, and the collection and analysis of large-scale data—have expanded the instruments of state repression and social control, turning into a reality that facilitates “digital authoritarianism.” In parallel, the online information ecosystem, a key aspect of democratic governance, began to deteriorate.

Keywords: digital authoritarianism and digital authoritarian practices, internet authoritarianism, digital repression.

Introduction

Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and social media have significantly expanded the means of social control. The installation of data collection systems, biometric and AI-powered data gathering and analysis tools allow for precise and large-scale monitoring of citizens. This, in turn, provides authoritarian governments with opportunities for both detailed and wide-reaching surveillance mechanisms. These capabilities make it easier for regimes to target offline and online dissenters and to exert control over specific groups. Countries like Russia and China have gone particularly far in using technology to consolidate power and suppress dissent and democratic demands, even developing global plans for the use of digital technologies for such purposes (Mantelassi, 2023a). For instance, although China’s well-known “social credit system” is presented as a nationwide, centralized, high-tech social control mechanism, reliable information and analyses of its implementation in certain cities, especially Tianjin, suggest it functions as a pilot project of digital authoritarianism (Cremer, Mattis, Hoffman, 2016).

Authoritarian regimes in the 21st century shape their political strategies around the reality that political debates and organizing now take place primarily in the digital sphere. This makes it easier for authoritarian regimes to restrict internet freedoms, impose full internet shutdowns, and control narratives through censorship—tools that have become globally recognized instruments of digital repression (Mantelassi, 2023b).

Methodological Basis

This research, prepared by the KHAR Center, is based primarily on informative analytical articles and reports by international organizations, drawing from conceptual approaches in academic sources and developed within historical and political contexts. Investigations conducted by media and civil society actors on this topic tend to be less academic and more practice-oriented, meaning the collected data largely reflects political contexts and experiences.

The goal of the research is to illustrate the essence and operating mechanisms of digital authoritarianism, to present how classical authoritarianism is being restructured in a modern technological framework, and to provide examples of new societal models being built by authoritarian regimes through systems of technological control.

The study is structured around the following questions: What practices can be considered elements of digital authoritarianism? Who (which actors) carries out digital authoritarianism, and for what purpose? What are the consequences of digital authoritarianism?

What Is Digital Authoritarianism?

The study of authoritarianism and repressive practices predates the digital era. The term “authoritarian” refers to regimes with absolute rulers (autocrats), non-electoral governments, and more broadly, those that routinely use censorship, surveillance, public opinion manipulation, and repressive legal regulations to suppress opposition and maintain power (Glasius, 2018). Digital authoritarianism, in turn, can be understood as the use of digital information technologies by states to exercise political control, carry out repression and surveillance, and strengthen their rule (Polyakova & Meserole, 2019).

The goal of digital authoritarianism is to preserve and expand power while ensuring the regime's security.

Digital technologies enable new authoritarian practices through tools such as algorithmic control, micro-targeted disinformation, and internet shutdowns. Studies into the elements of digital authoritarianism have been conducted since the 1980s in more than 40 countries, revealing through examples like surveillance of communications and control over television broadcasts that repressive authoritarian practices were already being implemented via the technologies available at the time (Roberts & Oosterom, 2024a).

The concept of digital authoritarianism gained prominence in the 2010s amid significant declines in political freedoms and increased use of digital technologies for state repression. The term “digital authoritarianism” was first used by Erikson and Li-Makiyama and gained traction after being cited in a U.S. House Committee on China hearing and featured in a “Freedom House” report (Freedom House, 2018). Initially applied to China and framed by some authors as specific only to authoritarian regimes, the concept later developed into two main conceptual approaches: one focused on digital practices in authoritarian regimes, the other on how similar practices are used in democracies and hybrid regimes.

Academic Differences in Approach

Steven Feldstein defines digital repression as “the use of information and communication technologies by states to monitor, coerce, or manipulate individuals or groups to suppress dissenting ideas or behaviors.” He categorizes digital repression into five areas: surveillance, censorship, social manipulation and disinformation, internet shutdowns, and targeted persecution of free-thinking users (Feldstein, 2021). Digital repression operates within a broader political repression ecosystem, tightly linked to state-imposed restrictions on civil liberties, such as censorship of political speech, banning of associations, and curbing academic freedoms. In countries with powerful security or intelligence services, digital repression not only reinforces existing mechanisms but also has the potential to reshape the state’s ability to monitor political opponents and suppress protest movements.

Studies on “networked authoritarianism” draw on academic materials from the 2000s that examine how governments exert control over the internet. The model of networked authoritarianism refers not to digital and mobile technologies broadly, but specifically to internet-focused “cyber-strategies” like content censorship, firewalls, and legal restrictions on online access (Li X., Lee F., & Li Y., 2016). These regimes often permit individuals greater online communication freedoms while simultaneously constraining this “freedom” through content control, censorship, and mechanisms for manipulating public opinion.

Tools of Digital Authoritarianism

Online censorship encompasses restrictive digital practices such as filtering the internet, blocking websites, banning keywords, limiting or shutting down internet access, and suppressing freedom of speech. In many countries, laws require internet companies, social media platforms, and internet cafes to monitor users and online content, often resulting in self-censorship (Sinpeng, 2013a). Governments invest in local infrastructure that can redirect internet traffic and allow shutdowns, website blocks, and content censorship (Sinpeng, 2013b).

Digital surveillance involves mass monitoring by security services not only of activists, journalists, and opposition politicians—so-called “persons of interest”—but of entire populations (Feldstein, 2021b). China is a prime example, with a high-tech surveillance architecture using AI for facial and voice recognition to identify and monitor individuals (Polyakova & Meserole, 2019b). The mandatory registration of SIM cards and use of biometric digital identification systems make it practically impossible to maintain anonymity. Research shows that authoritarian regimes have developed extensive legislation enabling digital surveillance and censorship to track dissenters (Roberts & Oosterom, 2024b).

Digital disinformation refers to false or distorted information intentionally spread or shared without awareness of its falsity (Freedom House, 2018). Recent studies show that governments are moving beyond simple digital repression tactics like blocking internet access and instead adopting more sophisticated strategies to manage public discourse within regime-aligned boundaries. Russia is among the leading countries employing such tactics both domestically and internationally.

In addition, manipulation, hate and hostility rhetoric, and psychological tactics aimed at controlling mass sentiment are widely used by authoritarian regimes in practice. The increasing sophistication and large-scale deployment of AI have created broader opportunities for the algorithmic development of digital authoritarianism.

Actors of Digital Authoritarianism

Actors involved in digital authoritarianism include both state and non-state entities (including regime-aligned “patriotic hackers” and private companies using bots and trolls). A real-world example is the “troll factory” operating in St. Petersburg, a private business project serving state interests (Volchek, 2021). The case of “patriotic hackers” supporting the Assad regime in Syria illustrates that digital authoritarianism can exist beyond population surveillance and take on transnational dimensions. “Patriotic hackers” are presented as “civilians with technological expertise who self-mobilize to engage in cyber-activism in defense of their country” (Conduit, 2023). The growing demand for technological infrastructure has led Western companies representing democratic societies to increasingly export tools necessary for digital authoritarianism to repressive regimes. For many authoritarian states—including China and Iran—investments in this field have evolved beyond “cybersovereignty” into projects of economic development. China’s model of internet state control functions not only as a tool of governance and repression but also as an economic investment sector with importance for both domestic and export markets (Freedom House, 2018b).

Mechanisms of Impact and Counter-Impact

The utility and effectiveness of digital technologies depend on the ability to adapt to new technologies and find innovative uses for them. In 2011, social media played a major role in mobilizing mass protests in the Arab world. As a result, governments in the region and beyond learned important lessons about how to use the same technologies to prevent protests, monitor dissent, and track demonstrators who spark unrest (Feldstein, 2021c). Digital tools offer wide-ranging capabilities: for civil society activists to connect and protest against governments, and for regimes to surveil dissenters, control public discourse, and disseminate disinformation. Repression through digital technologies against civil society, media, and other spheres by authoritarian regimes undermines trust in activists, politicians, and journalists, while also damaging institutional functionality. This practice has shifted the global paradigm of digital technology use in politics. Research predicts that the cycle of technological innovation will further intensify the global struggle between autocratic regimes using communication technologies for control and the civil society actors resisting them with the same tools (Roberts & Oosterom, 2024c).

The Normative Framework of Digital Authoritarianism

Authoritarian regimes seek to legitimize and legalize state intervention aimed at controlling citizens, repressing dissent, and regulating institutional activity in society through the creation of a legal framework that enables top‑down governance via digital technologies. These regimes operationalize such control within two main dimensions — ideological and institutional. The ideological framework shapes public opinion and provides a moral justification for repressive measures, while the institutional framework consists of concrete state organs and structures that implement this ideology through legal instruments.

Combating terrorism and extremism has become one of the most popular ideological tools employed by 21st‑century authoritarian regimes. Under the pretext of ensuring public safety and protecting citizens from threats, authorities adopt laws that prohibit online anonymity, enable mass surveillance, and restrict freedom of expression. For instance, in Kazakhstan, legislative amendments banning bloggers’ anonymity were justified as part of anti‑terrorism measures (Freedom House, 2023).

The propaganda of “traditional values” or “morality” is also used to justify legal steps that suppress public activism and silence criticism of government policies. The Iranian case clearly demonstrates the use of such ideology, where legislation on “moral values” forms the foundation of digital censorship. In Iran, the enforcement of digital censorship and surveillance under the pretext of protecting “national security” or preventing threats to “moral values” has become a common practice.

Narratives such as the protection of “national security,” “stability,” and “law and order” serve as the underlying justifications for adopting normative acts designed to suppress public resistance and discontent.

State institutions become instrumentalized within this institutional framework. For example, in Russia, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media — known as Roskomnadzor — is the body responsible for implementing internet censorship, blocking critical websites, and enforcing the “sovereign internet” law (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2019).

Judicial institutions are subordinated to political interests and used to legalize measures that ensure regime survival. By issuing politically motivated rulings, courts confer legitimacy upon repressive laws (KHAR Center, 2025).

State‑owned media and propaganda apparatuses dominate the information space, disseminating official ideology, discrediting the opposition, and shaping public perception of government actions as both necessary and legitimate. In Azerbaijan, the government’s control is manifested in the hegemony of pro‑government TV channels and the fact that the National Television and Radio Council (NTRC), which regulates and approves broadcasting licenses, was established and is financed by the state itself (Amnesty International, 2011).

In addition, in some countries, the normative framework governing digital authoritarianism is regulated through unrelated legal instruments — including construction codes, tax laws, criminal codes, and intellectual property laws.

Legal mechanisms are also being developed to enable digital authoritarianism to transcend national borders and evolve into transnational cooperation. For example, Russia’s digital technology cooperation with former Soviet republics is regulated through “information security” treaties it has signed with them (Russian MFA, 2017).

The Pollution of the Information Ecosystem

The survival of democracy depends on the free flow of reliable and fact‑based information. In the 21st century, this free flow primarily occurs online, especially on social media platforms — key branches of digital infrastructure. In this context, the interference in the 2016 U.S. elections and the Brexit referendum through disinformation and manipulative tactics can be considered a shocking revelation for the foundations of democracy (Steinwehr, 2017). The recent Moldovan elections also demonstrated that this dynamic has since become a normalized tool for exporting and spreading authoritarian influence (Meduza, 2025). This illustrates how digital technologies can be used to contaminate and erode the information ecosystem — a core pillar of democratic governance — thereby degrading democratic systems (Rest of World).

Disinformation campaigns and manipulations that pollute the information ecosystem are often carried out by trolls who create, disseminate, and amplify false stories online. Such waves of disinformation largely stem from the algorithmic dynamics underlying social media content recommendations, which prioritize emotionally charged content to maximize user engagement. This, in turn, facilitates the spread of sensational and false political messages while trapping users within deliberately constructed content bubbles. The result is a digital space saturated with falsehoods and an obstruction of users’ exposure to diverse and alternative information sources. This polluted informational ecosystem undermines healthy democratic discourse.

The Geography of Digital Authoritarianism

A systematic monitoring of 105 academic papers published in 2024 on digital authoritarianism revealed significant geographical asymmetry in country‑specific research focus (Roberts & Oosterom, 2024b). Most studies focus on China, followed by Russia; the only other countries covered by multiple articles are Iran and Syria. However, there is a lack of in‑depth research on countries such as Eritrea, Nicaragua, Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Belarus — regimes that rank even higher than China on the authoritarian scale in the V‑DEM Democracy Index, likely due to the unavailability of reliable data (V‑DEM, 2024).

Digital authoritarian practices are also widespread across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. For example, Malaysia applies facial recognition technology within its army; Singapore is integrating it into a nationwide street‑camera network; and Ethiopia’s security forces use telecommunications equipment from ZTE to monitor opposition activists and journalists (Polyakova & Meserole, 2019c). In Dubai, a project called “Police Without Police” replaces human officers with video surveillance and facial recognition systems based on Chinese technologies (Gulf News, 2018).

In post‑Soviet autocracies, the following types of digital authoritarianism are prevalent (Access Now, 2022):

- Online censorship: restricting free speech, blocking independent media and internet resources;

- Internet shutdowns: deliberate disruptions of internet networks and blocking of communication platforms;

- Disinformation and hate speech: state‑funded propaganda and disinformation campaigns, as well as the promotion of hostility and hatred;

- Surveillance: the use of spyware against critics, mass monitoring of personal data, including biometric tracking.

The country where digital authoritarianism is most developed and constantly refined is China — simultaneously the flagship and the largest exporter of digital authoritarian practices.

The Mechanisms of Exporting Digital Authoritarianism

The global and interconnected nature of the internet has made authoritarianism increasingly transnational in the 21st century. This transnational character plays a key role in exporting and spreading digital authoritarianism, enabling similar regimes to dynamically replicate their models elsewhere. At the same time, authoritarian governments exploit existing social and political tensions in democracies via digital technologies to deepen radical tendencies, sow distrust in democratic institutions and processes, and discredit democracy domestically.

Furthermore, transnational campaigns of surveillance and hacking targeting activists and regime critics abroad — including digital threats, spyware‑based harassment, and intimidation — exemplify how digital authoritarianism penetrates the geography of democracy. Transnational digital authoritarianism is particularly cost‑effective, as it requires no physical travel. Governments such as those of China, Qatar, Russia, Iran, Rwanda, and Saudi Arabia are notable for threatening and monitoring their citizens living abroad (Lamensch, 2021).

The technologies enabling digital authoritarianism are often developed and sold by Western companies, meaning Western countries indirectly participate in the market for control technologies that benefit repressive regimes. For example, after the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus, the government used website‑blocking technology purchased from Sandvine, a U.S. company headquartered in Canada, to restrict internet access (Gallagher, 2020). In 2021, the directors of French firms Amesys and Nexa Technologies were charged with supplying surveillance technologies to the governments of Libya and Egypt, allegedly facilitating torture and enforced disappearances (MIT Technology Review, 2021).

Regimes such as those of China, Saudi Arabia, and Russia export not only repressive technologies but also data architectures and surveillance methodologies. China’s extensive use of digital tools for censorship and surveillance has made it a preferred supplier for illiberal regimes — 24 governments, particularly in sub‑Saharan Africa, now employ Chinese surveillance technologies (Feldstein, 2020). According to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI, 2019), China’s expanding global presence of tech firms has made it a model of digital authoritarianism for non‑democratic states.

Globally, many countries with similar capacities and resources to Russia prefer the Kremlin’s model of digital authoritarianism because it offers a less advanced yet cheaper alternative compared to the Chinese model.

For Beijing, the export of information technologies provides not only significant new revenue and data resources but also the formation of major strategic influence over the West. A striking example occurred during the 47th session of the UN Human Rights Council, when Canada’s initiative to investigate human rights abuses against Uyghurs received support from 44 countries, while 65 others sided with China and condemned “politically motivated, baseless accusations against China based on disinformation” (Feng, 2021).

Signs of Digital Authoritarianism in Democracies

The global decline of democracy coincides with the rapid development of new technologies for data collection, communication, and surveillance (Mantelassi, 2023c). The capacity of digital technologies to undermine democracy and reinforce authoritarianism is not confined to rigid autocracies — it has also become a global phenomenon affecting democratic regimes. A significant portion of the technologies that enable authoritarian control originate from the West and are widely used in democratic states.

Countries such as the United States, Germany, France, and Japan are both sellers and users of such technologies. As these technologies evolve, Western democracies themselves become increasingly entangled in digital authoritarianism, facing growing risks of misuse. For example, digital tracking applications introduced during the COVID‑19 pandemic provoked serious debates (SSRC, 2021). The discussions centered on how these tools, lacking adequate legal safeguards, infringed on the right to privacy and normalized state surveillance over citizens (Mantelassi, 2021). Another example is the protests by NGOs in the United Kingdom against the use of facial recognition technology by police (Big Brother Watch, 2023).

Modern technologies, on one hand, make it possible to carry out large‑scale, automated, continuous, cost‑effective, and targeted surveillance; on the other hand, they increase the likelihood that governments will exploit these capabilities in ways incompatible with democratic standards, privacy principles, and human rights. Although they may not always be used for social control, the 2013 Snowden revelations exposed the full scope of problematic domestic and international digital surveillance mechanisms in the United States (The Guardian, 2013).

The ability of tech corporations to influence consumer behavior through targeted advertising has also spread into the political sphere, with devastating consequences for democracy (Feldstein, 2019). Unprecedented and unrestrained access to citizens’ personal data has granted private and unaccountable corporations extraordinary power over public and political life, including the ability to influence voters’ choices in elections.

The Chinese Model of Digital Authoritarianism

Research shows notable differences between Chinese and Russian approaches to digital authoritarianism. Unlike Russia, which relies more on cost‑effective disinformation tactics, China focuses on high‑technology surveillance systems.

Beijing employs information technologies for both online and offline control. Applications and websites that fail to comply with government requirements are blocked, while internet censorship is enforced through the so‑called Great Firewall.

In 2005, China’s Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology launched a project aimed at installing cameras across public spaces and key industrial sectors (Zhang, 2012). Integrating smartphones, smart TVs, and surveillance cameras, this project enables the state to monitor citizens’ movements and behaviors in detail. Artificial intelligence is used to identify and track individuals. One of the most ambitious initiatives in 2018 aimed to develop a system capable of processing 100,000 high‑definition video streams simultaneously and tracking people in real time (Bloomberg, 2018).

The first experiment with this network was conducted by police: in May 2018, during a concert in Tianjin, a facial recognition program alerted security services that one of the 60,000 spectators was a wanted suspect, who was located and arrested within minutes (Wang, 2018). Tianjin — a region populated by Uyghurs — has become a testing ground for Beijing’s most repressive technologies. Uyghurs are frequently subjected to DNA testing and iris scans at police checkpoints (Haas, 2017); spyware is installed on their phones to monitor online activity, and navigation systems are embedded in their vehicles (Kieren, 2017). In areas without surveillance cameras, small bird‑like drones are deployed to monitor movements from above (Chen, 2018).

Alongside this total surveillance and data collection system, China has introduced a social credit system (SCS) — a mechanism designed to evaluate citizens’ loyalty to the government (RBC, 2016).

Citizens who comply with state‑defined rules receive privileges, while violators are punished. Points are awarded for law‑abiding behavior and positive civic contributions, such as timely loan repayments, while points are deducted for infractions. Those failing to reach the required “passing score” find everyday life severely restricted. The penalties imposed on low‑scoring citizens include:

— prohibition from working in state institutions;

— denial of social benefits;

— intensive customs inspections;

— bans on holding managerial positions in food and pharmaceutical industries;

— denial of flight tickets and sleeper train berths;

— refusal of service in luxury hotels and restaurants;

— prohibition of children’s enrollment in expensive private schools.

Researchers have described China’s model as an Orwellian dystopia (Chin & Wong, 2016). The situation observed in China stands as one of the most striking examples of digital totalitarianism in the modern world.

The Russian Model of Digital Authoritarianism

Unlike China, Russia does not rely heavily on the widespread application of high-tech systems that require extensive resources. Instead, it integrates elements of digital totalitarianism into public life primarily through institutional mechanisms to place society under total control.

Since the 1990s, the government has begun adapting Soviet-era surveillance technologies, known as the System of Operative Investigative Measures (SORM), to the digital sphere. However, rather than focusing on filtering information before it reaches the public, the Russian government has prioritized establishing a repressive legal regime that tightens control over information and keeps internet providers, telecommunications operators, private companies, and civil society groups under threat (Freedom House, 2018a).

Since the early 2000s, the Russian state has passed a series of laws that have effectively criminalized criticism of the government, legalized unlimited surveillance of citizens’ online activity, and strengthened state control over the Russian internet (RuNet) (Meduza, 2019). From 2014 onward, the government began taking legal and technical steps to create a "sovereign internet" modeled after China’s system. In May 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the Sovereign Internet Law, granting the state media regulator Roskomnadzor the authority to take control of the Russian internet if it becomes disconnected from the global network (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2019).

Additionally, several government agencies have been granted the authority to block content without a court order (Freedom House, 2018b). In the fall of 2017, President Putin signed a law allowing the Russian government to label media outlets receiving foreign funding as “foreign agents” (President of Russia, 2017). This law gave Russian authorities broad powers to block online content, including social media websites deemed “undesirable” or “extremist.” A law passed in January 2018 banned anonymity for users of social media and communication platforms (Polyakova, 2017).

Attempts by users in Russia to access foreign internet resources via VPNs or other tools are restricted by regulations and punishable by law. According to a law passed by the State Duma, citizens who search the internet for content related to individuals or groups labeled by the government as extremists, terrorists, foreign agents, or critics of the regime — including content critical of Russian state policy — can be held criminally liable (TASS, 2025). In an earlier stage, many critics of the regime — including journalists, human rights defenders, academics, artists, and teachers — were already labeled as “foreign agents” by law enforcement authorities.

Access to websites of U.S.-based companies such as YouTube is restricted in Russia. Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram) and X (formerly Twitter) have been banned as extremist organizations. At the same time, under the concept of a “sovereign internet,” the Russian government has launched new state-controlled social media platforms and applications under the oversight of the Federal Security Service (FSB) (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 2019b). This provides the state with control not only over the content of online information but also over the physical infrastructure of the internet. While the concept of a sovereign internet has been discussed for years, its full-scale implementation began following Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Russia has also drawn on certain Chinese digital surveillance and control projects. For instance, beginning in September 2025, an experimental regime will be introduced in Moscow to monitor migrants using a mobile application modeled after China’s surveillance program targeting Uyghurs (Embassy of the Republic of Azerbaijan, 2025). The system, accessed via a special app, will be mandatory for all migrants. Starting from September 1, 2026, the project will also apply to all foreign nationals who stay in Russia for more than 90 days, even if not for work.

Among the mechanisms of digital authoritarianism, disinformation and censorship are used more broadly in Russia than in many other cases. The state actively uses online media in propaganda and disinformation campaigns to incite hatred against targeted individuals or communities. Trolls and bots play a major role in polluting the Russian-language information ecosystem (Radio Azadlıq/Radio Liberty, 2018).

Online censorship in Russia is not limited to disproportionate restrictions on freedom of speech, blocking of independent media and civil society websites. It also involves repressive legislation that aims to intimidate and push these actors into self-censorship.

Russia’s low-tech surveillance model is attractive to low-resource governments that lack China’s economic power, human capital, and centralized state control. Its affordability and adaptability make it an appealing alternative.

Tools of Digital Authoritarianism Used in Azerbaijan

Research shows that the tools of digital authoritarianism most commonly used in Azerbaijan include surveillance, online censorship, disinformation, and hate speech (Geybulla, 2019). During the 44-day war in 2020 and in times of mass protests, instances of restricted or blocked access to social media platforms were observed.

The Azerbaijani government imports surveillance technologies from abroad. For instance, the “Pegasus” spyware developed by the Israeli cyber-intelligence company NSO Group has enabled the government not only to track its critics, but also to automatically turn everyone in the infected phone owner’s contact circle into surveillance targets (Patrucic & Bloss, 2012). Pegasus is capable of recording phone calls, reading text messages, accessing photos and passwords, tracking GPS location, and secretly activating audio and video recordings — all of which can be transmitted to covert operators.

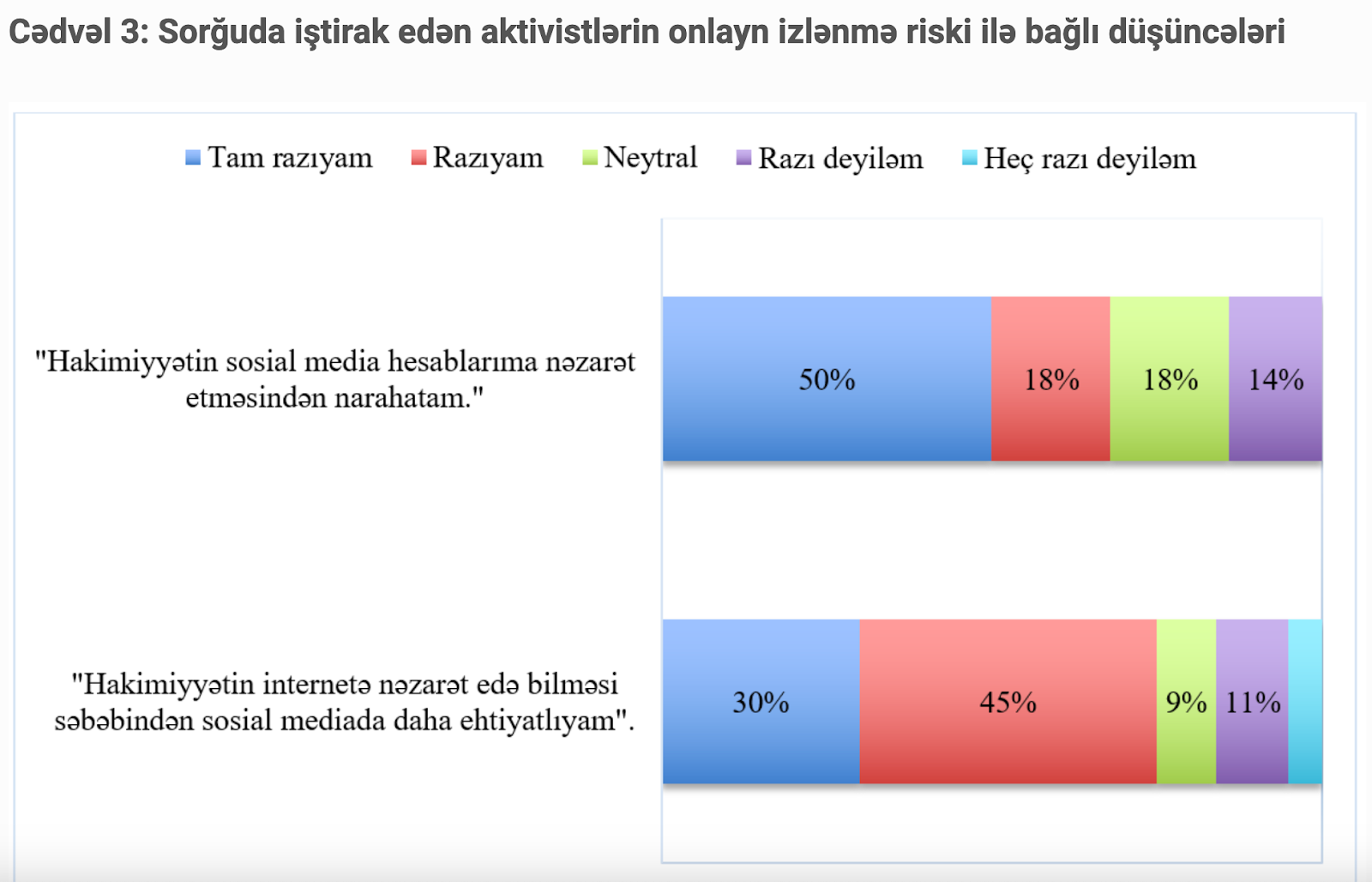

According to the results of a 2023 survey conducted by the Baku Research Institute among Azerbaijani civic and political activists, 68% of respondents expressed concern about the government’s monitoring of their online accounts and activities. Furthermore, 75% of participants stated that due to the government’s capacity to control the internet, they were cautious when using social media (Kamilsoy & Bedford, 2023a).

Online Censorship, Disinformation, and the Future of Digital Authoritarianism

Online censorship in Azerbaijan not only restricts freedom of expression in the digital space but also functions as a repressive tool to compel network users into self-censorship. This has, in turn, led to hesitation among activists in using social media, forced them to adjust their behavior, become more cautious, and even avoid using direct messaging features on social platforms for political communication.

In Azerbaijan, along with local independent media websites, the local services of international media outlets such as Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and Voice of America have also been blocked. This restricts citizens’ access to alternative sources of information. Against the backdrop of the government-controlled, high-volume flow of information, the limited availability of alternative content renders citizens vulnerable and defenseless in the face of disinformation and manipulation.

The government has succeeded in spreading disinformation and manipulating public opinion via social media, online news platforms, and other internet resources, as well as through fake accounts and trolls.

In 2019, Facebook’s former data specialist Sophie Zhang identified a troll network consisting of thousands of fake accounts that posted “approximately 2.1 million negative and abusive comments” targeting civic activists, critics of the government, and independent media in Azerbaijan. Her investigation revealed that this troll network was operated by the ruling New Azerbaijan Party and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Kamilsoy & Bedford, 2023b).

Furthermore, under the direction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, surveillance cameras have been installed across nearly all streets of Baku as part of the “Safe City” project. The Azerbaijani government has tested China’s repressive model of technological surveillance on a smaller scale. For instance, by installing special surveillance cameras in areas designated for opposition protests, police were able to identify citizens who participated in rallies (Qafqaz.info, 2019).

Conclusion

There is a global trend of democratic backsliding, and the role of digital technologies in this decline cannot be ignored. Mechanisms of digital authoritarianism — the use of digital information technologies by authoritarian regimes to monitor, suppress, and manipulate both domestic and foreign populations — are altering the balance of power between democracies and autocracies.

The expansion of repressive digital tools by governments has disrupted the information ecosystem that is vital to democratic governance. The increasing capabilities of private tech companies and the rapid development of digital technologies have contributed to the strengthening of authoritarianism and the growing fragility of democracy. This contradiction stems from the realization by authoritarian regimes that digital technologies can serve the interests of authoritarianism — leading them to invest in digital innovations and to develop techniques aimed at dismantling the civic and political activism of critics on social media.

Authoritarian regimes are increasingly interested in monitoring public opinion. Thus, online citizen participation via social media has become an important tool for tracking public sentiment. In such regimes, citizen participation online should not be interpreted as influencing decision-making mechanisms but rather as a means for gathering information.

These regimes may allow relatively free online communication but simultaneously take various measures to prevent it from becoming a threat. In this sense, the government is not only a regulator of the internet space but also an active participant.

China and Russia have mastered the use of the internet and information technologies as tools of repression designed to limit individual freedom. Simultaneously, they have begun to export their digital authoritarian models globally. In the absence of effective democratic responses — including international frameworks regulating the export of surveillance technologies — progress in the field of information technology risks leading not to liberalization, but to a future of intensifying repression.

Full digitalization and unrestricted state access to personal data by authoritarian regimes such as China and Russia could result in total control over individuals — and most dangerously, deprive individuals of the ability to act outside the regime’s oversight. The ongoing refinement and transnational export of China and Russia’s digital authoritarian models have become a significantly dangerous trend.

Authoritarian regimes in the post-Soviet space — including Azerbaijan — are not only borrowing from authoritarian practices but also importing and applying the tools and operational mechanisms of “advanced regimes” in digital authoritarianism. This process expands the geographic reach of digital authoritarianism, fuels economic activity in this domain, and contributes to the survival and reinforcement of authoritarian regimes.

Research shows that even very weak or illiberal democracies make use of digital repression tools. Countries such as India, Brazil, Turkey, the Philippines, Nigeria, Serbia, and Hungary widely implement tactics ranging from internet shutdowns and disinformation to social media censorship (e.g., the Twitter ban in Nigeria or the adoption of a new social media law in Turkey requiring content removal) (Feldstein, 2021d).

Overall, partially democratic countries are more likely to rely on manipulative strategies such as disinformation campaigns rather than harsher measures like mass surveillance or widespread website censorship. Thus, this new form of authoritarianism is built not on mass violence but on information manipulation. The result is the restriction of human rights and civil liberties and the expansion of control over citizens.

One of the key challenges in countering the global authoritarian trend is the need to clean up the information environment — a task that should be made a priority of security policy. Factual accuracy and evidence-based political debate nourish democracy, while disinformation and manipulation fuel autocracy.

The failure of liberal democracies to provide attractive and economically viable alternatives to China’s model of digital governance and infrastructure has facilitated the spread of authoritarian tools that Beijing has been developing at home for years.

Studies indicate that one potential mechanism for curbing digital authoritarianism would be the imposition of strict sanctions on companies in China, Russia, the United States, Europe, and Israel that supply such regimes with surveillance technology. In addition, democratic governments and international organizations can strengthen export controls and verification mechanisms to prevent the use of technology that undermines democratic governance.

It would be a crucial step for the West to develop a democratic model of digital governance that surpasses authoritarian systems. One possible path forward is for technology sectors and political circles in the United States and Europe to propose attractive models of digital surveillance that enhance security while simultaneously safeguarding civil liberties and human rights.

Research on digital authoritarianism shows that most studies carried out by political and civil society actors are less academic and more practice-oriented, often containing policy- and action-oriented recommendations. To more effectively translate available evidence and documentation into informed policy and practice, joint research involving civil society organizations active in this field would be highly beneficial.

References

Mantelassi Federico. 2023a. Digital Authoritarianism: How Digital Technologies Can Empower Authoritarianism and Weaken Democracy. GCSP. 16 February

Cremers Rogier, Mattis Peter, Hoffman Samantha. 2016. What Could China’s ‘Social Credit System’ Mean for its Citizens? Foreign Policy. 15 August.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/08/15/what-could-chinas-social-credit-system-mean-for-its-citizens/

Mantelassi Federico. 2023b. Digital Authoritarianism: How Digital Technologies Can Empower Authoritarianism and Weaken Democracy. GCSP. 16 February

Glasius Marlies. 2018. What authoritarianism is … and is not: A practice perspective. International Affairs. 3 May

https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy060

Polyakova and Chris Meserole, 2019a. Exporting digital authoritarianism:The Russian and Chinese models.

Roberts Tony & Oosterom Marjoke. 2024a. Digital authoritarianism: a systematic literature review

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02681102.2024.2425352#abstract

Freedom House. 2018a. The rise of digital authoritarianism.

https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism

Feldstein Steven. 2021a. Digital Technology’s Evolving Role in Politics, Protest and Repression. United States Institute of Peace. 21 July

Li X., Lee F., & Li Y. (2016). The dual impact of social media under networked authoritarianism: Social media use, civic attitudes, and system support in China. International Journal of Communication

5163. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/5298/1817

Sinpeng, A. 2013. State repression in cyberspace: The case of Thailand. Asian Politics & Policy

https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12036

Sinpeng, A. 2013. State repression in cyberspace: The case of Thailand. Asian Politics & Policy

https://doi.org/10.1111/aspp.12036

Feldstein Steven. 2021b. Digital Technology’s Evolving Role in Politics, Protest and Repression. United States Institute of Peace. 21 July

Polyakova A. and Meserole C. 2019b. Exporting digital authoritarianism:The Russian and Chinese models.

Roberts Tony & Oosterom Marjoke. 2024b. Digital authoritarianism: a systematic literature review

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02681102.2024.2425352#abstract

Freedom House. 2018b. The rise of digital authoritarianism. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism

Дмитрий В. 2021. "Наша норма – 120 комментов в день". Жизнь кремлевского тролля. Радио Свобода. 24 January

https://www.svoboda.org/a/31065181.html

Conduit Dara. 2023. Digital authoritarianism and the devolution of authoritarian rule: Examining Syria’s patriotic hackers

https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2023.2187781

Freedom House. 2018b. The rise of digital authoritarianism. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/rise-digital-authoritarianism

Feldstein Steven. 2021c. Digital Technology’s Evolving Role in Politics, Protest and Repression. United States Institute of Peace. 21 July

Roberts Tony & Oosterom Marjoke. 2024c. Digital authoritarianism: a systematic literature review

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02681102.2024.2425352#abstract

Freedom House. 2023. Freedom on the net 2023

Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty. 2019a. Putin Signs ‘Sovereign Internet’ Law, Expanding Government Control of Internet. 1 May

Khar Center. 2025. Azərbaycan mediası üzərində hibrid nəzarət: kooptasiya–repressiya tandem. Xəzər Tədqiqat və Analiz Mərkəzi. 28 October

Amnesty International. 2011. Heç vaxt çiçəklənməyən bahar: Azərbaycanda azadlıqlar tapdanır. November

https://www.amnesty.org/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/eur550112011az.pdf

МИД России. 2017. Перечень многосторонних международных договоров Российской Федерации. 30 November

Штайнвер Ута. 2017. Почему фейковые новости - угроза демократии. Deutsche Welle.

13 January

Медуза. 2025. В Молдове скоро выборы. У России есть план, как на них повлиять. 22 September

Rest of world. How misinformation spreads around the world

https://restofworld.org/collection/misinformation-and-its-effects-around-the-world/

Roberts Tony & Oosterom Marjoke. 2024b. Digital authoritarianism: a systematic literature review

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02681102.2024.2425352#abstract

V-DEM. 2024. Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot

https://www.v-dem.net/documents/44/v-dem_dr2024_highres.pdf(open in a new window)

Polyakova A. and Meserole C. 2019c. Exporting digital authoritarianism:The Russian and Chinese models.

Gulf News. 2018. Dubai rolls out ‘Police without Policemen’ initiative. 12 March https://gulfnews.com/uae/crime/dubai-rolls-out-police-without-policemen-initiative-1.2186841

Accessnow. 2022. Digital dictatorship. October

Lamensch Marie. 2021. Authoritarianism Has Been Reinvented for the Digital Age. The Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI). 9 July

https://www.cigionline.org/articles/authoritarianism-has-been-reinvented-for-the-digital-age/

Gallagher Ryan. 2020. U.S. Company Faces Backlash After Belarus Uses Its Tech to Block Internet. Bloomberg. 11September

MIT Technology Review. 2021. French spyware bosses indicted for their role in the torture of dissidents. 22 June

Feldstein Steven. 2020. When it Comes to Digital Authoritarianism, China is a Challenge — But Not the Only Challenge. War on the rocks. 21 February

ASPI. 2019. Mapping China’s Tech Giants. 18 April

https://www.aspi.org.au/report/mapping-chinas-tech-giants/

Feng John. 2021. China Backed by 65 Nations on Human Rights Despite Xinjiang Concerns. Newsweek. 23 June.

https://www.newsweek.com/support-chinas-human-rights-polices-doubles-among-un-members-1603246

Mantelassi Federico. 2023с. Digital Authoritarianism: How Digital Technologies Can Empower Authoritarianism and Weaken Democracy. GCSP. 16 February

SSRC. 2021. Surveillance and the “new normal” of COVID-19: Public Health, Data, and Justice. The Social Science Research Council

Mantelassi Federico. 2021. Tracking Covid: Apps and Privacy. The GAP. 14 May

https://www.the-gap.ch/2021/05/14/covid-tracking/

Big Brother Watch. 2023. Stop Facial Recognition

https://bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/campaigns/stop-facial-recognition/

The Guardian. 2013. What the revelations mean for you. 1 November

Feldstein Steven. 2019. The Global Expansion of AI Surveillance. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Zhang Zihan. 2012. Beijing’s guardian angels?. Global Times. 10 October

http://www.globaltimes. cn/content/737491.shtml

Bloomberg. 2018. China Now Has the Most Valuable AI Startup in the World. 8 April

Wang Amy B. 2018. A suspect tried to blend in with 60,000 concertgoers. China’s facial-recognition cameras caught him. The Washington Post. 13 April https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/ worldviews/wp/2018/04/13/china-crime-facial-recognition-cameras-catch-suspect-at-concert-with60000-people/?utm_term=.e0ad09991412

Haas Benjamin. 2017. Chinese authorities collecting DNA from all residents of Xinjiang. The Guardian. 17 December

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/13/chinese-authorities-collectingdna-residents-xinjiang

Kieren McCarthy. 2017. China crams spyware on phones in Muslim-majority province. The Register. 24 July

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/07/24/china_installing_mobile_spyware/

Chen Stephen. 2018. China takes surveillance to new heights with flock of robotic Doves, but do they come in peace?. South China Morning Post, 24 June https://www.scmp.com/news/china/society/ article/2152027/china-takes-surveillance-new-heights-flock-robotic-doves-do-they

RBC. 2016. Цифровая диктатура: как в Китае вводят систему социального рейтинга. 11 December.

https://www.rbc.ru/business/11/12/2016/584953bb9a79477c8a7c08a7

Chin Josh & Wong Gillian. 2016. China’s New Tool for Social Control: A Credit Rating for Everything. The Washington Post. 28 November

Freedom House. 2018a. “Freedom on the Net 2018: Russia.

https:// freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/russia

Meduza. 2019. Путин подписал закон об изоляции Рунета. 1 May

https://meduza.io/news/2019/05/01/putin-podpisal-zakon-ob-izolyatsii-runeta

Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty. 2019a. Putin Signs ‘Sovereign Internet’ Law, Expanding Government Control of Internet. 1 May

Freedom House. 2018b. “Freedom on the Net 2018: Russia.

https:// freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2018/Russia

Президент России. 2017. Внесены изменения в закон об информации и в закон о СМИ. 25 November

http://kremlin.ru/acts/news/56179

Polyakova Alina. 2017. The Kremlin’s Latest Crackdown on Independent Media: Russia’s New Foreign Agent Law in Context. Foreign Affairs. 5 December https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/ russia-fsu/2017-12-05/kremlins-latest-crackdown-independent-media

ТАСС. 2025. Госдума приняла закон о штрафах за поиск экстремистских материалов. Что это значит?. 22 July

https://tass.ru/obschestvo/24530603

Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty. 2019b. Putin Signs ‘Sovereign Internet’ Law, Expanding Government Control of Internet. 1 May

Azərbaycan Respublikasının Rusiya Federasiyasında Səfirliyi. 2025. Əcnəbi vətəndaşlar üçün "Amina" tətbiqi haqqında mühüm məlumat. 10 September

Azadlıq Radiosu. 2018. Müxalifət: 'Təşkilatlanmış şərhçilər axşam 6-ya qədər işləyirlər'. 9 February

https://www.azadliq.org/a/hakimiyyet-trollar/29031155.html

Geybulla Arzu. 2019. In Azerbaijan, big brother is watching you everywhere: offline, online, on mobile devices and social media apps. The Foreign Policy Centre. 15 January

Patrucic M. & Bloss K. 2012. Life in Azerbaijan’s Digital Autocracy: ‘They Want to be in Control of Everything’. OCCRP. 30 July

Kamilsoy Nəcmin & Bedford Sofie. 2023a. Azərbaycanda rəqəmsal avtoritarizm və aktivistlərin sosial media qavramaları. Baku Research Institute. 21August

Kamilsoy Nəcmin & Bedford Sofie. 2023b. Azərbaycanda rəqəmsal avtoritarizm və aktivistlərin sosial media qavramaları. Baku Research Institute. 21August

Qafqaz.info. 2019. Mitinqdə iştirak edənlərin siyahısı tutulur. 16 January

https://qafqazinfo.az/news/detail/hokumetin-milli-suranin-mitinqi-ile-bagli-plani-240911

Feldstein Steven. 2021d. Digital Technology’s Evolving Role in Politics, Protest and Repression. United States Institute of Peace. 21 July