This research analyzes the evolution of authoritarianism in Uzbekistan since 1991, focusing on two major phases: the repressive personalist regime of Islam Karimov and the era of modernization under authoritarian control led by Shavkat Mirziyoyev. The research applies a theoretical framework incorporating approaches such as personalist authoritarianism, dynastic authoritarianism, electoral authoritarianism, hybrid regimes, and authoritarian modernization.

The study demonstrates how the reforms implemented during Mirziyoyev’s rule have enhanced the regime’s adaptability and international image, while ultimately preserving the authoritarian nature of governance. The case of Uzbekistan provides a valuable empirical foundation for understanding the stability and transformation mechanisms of authoritarian regimes in Central Asia. In this context, the country serves as a model of regime durability achieved through authoritarian modernization, selective reforms, and a transition to dynastic rule.

Introduction

Relevance and Scholarly Significance of the Topic

Central Asia is one of the most prominent regions in the post-Soviet space where durable forms of authoritarianism have taken root. Political transition models in the region have not trended toward democratization but rather have been characterized by adaptations to entrenched authoritarian norms (Matveeva, 2009; Lewis, 2008). Uzbekistan stands out in this regard: on the one hand, under the 25-year rule of Islam Karimov, it exemplified a classical repressive personalist authoritarian regime; on the other hand, under Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the country has transitioned to a model of "authoritarian modernization" marked by liberal rhetoric and reform discourse (Anceschi, 2020).

In political science, the stability and transformation mechanisms of authoritarian regimes have become a growing area of inquiry. Notably, Levitsky and Way’s concept of “competitive authoritarianism,” Schedler’s theory of “electoral authoritarianism,” and Heydemann’s model of “authoritarian upgrading” offer frameworks to explain the adaptability and resilience of such regimes. Analyzing Uzbekistan through these lenses contributes significantly to both empirical and theoretical scholarship on authoritarianism in the region.

Moreover, Uzbekistan’s political development cannot be isolated from its geopolitical context. The country’s position is shaped by the influence of regional powers like Russia and China, as well as economic cooperation with the European Union and the United States (Cooley, 2012). Therefore, the evolution of authoritarianism in Uzbekistan has theoretical relevance and strategic significance for both political science discourse and applied policy analysis.

Research Objectives

This study aims to comparatively analyze the historical trajectory and institutional foundations of authoritarian governance in Uzbekistan. The following objectives are outlined:

- To examine the historical and institutional foundations of the authoritarian governance model that developed in Uzbekistan following independence;

- To identify the key characteristics of the personalist, repressive, and centralized regime under Islam Karimov and assess its impact on political institutions;

- To evaluate the effect of political and administrative reforms under Shavkat Mirziyoyev on the nature of the regime;

- To empirically determine whether structural changes occurred within the regime and assess whether such changes indicate authoritarian stability or transformation;

- To generalize the tendencies of continuity and change in the regime through a comparative analysis of both eras.

Research Questions

- What are the institutional foundations of authoritarian rule in Uzbekistan?

- Have the reforms under Mirziyoyev transformed the essence of the regime?

Methodology

This study employs comparative analysis of political regime theories and empirical developments.

Theoretical Framework

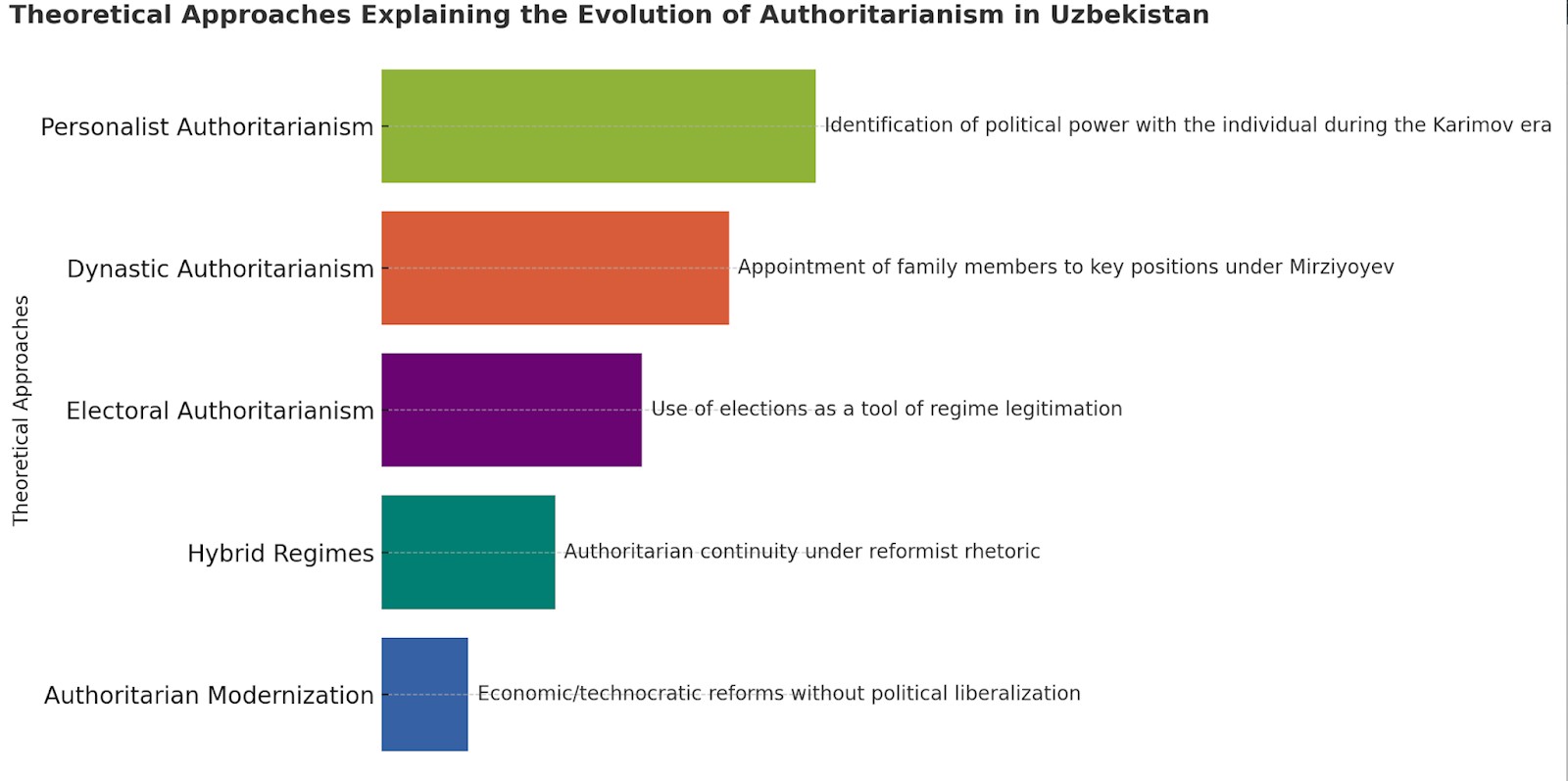

Understanding the evolution of authoritarianism in Uzbekistan requires the integration of multiple theoretical approaches. This study draws on the following frameworks: personalist authoritarianism (Geddes, 2003), dynastic authoritarianism (Brownlee, 2007), electoral authoritarianism (Schedler, 2006), hybrid regimes (Levitsky & Way, 2010), and authoritarian modernization (Heydemann, 2007).

Personalist Authoritarianism:

Within Barbara Geddes’s classification, personalist regimes are characterized by a concentration of power in the hands of a single leader whose personal will overrides institutional constraints. In such regimes, political decisions are centralized around the leader rather than a broader elite (Geddes, 2003a).

This model aptly describes the period of Islam Karimov’s rule (1989–2016). During his long tenure, actual political power was concentrated around his personal leadership. State institutions such as political parties, security services, and the judiciary were directed based on his personal decisions. As Geddes emphasizes, personalist regimes are especially vulnerable to instability upon the leader’s death or ousting—a pattern that materialized in Uzbekistan following Karimov’s death in 2016 (Frantz, 2014).

Dynastic Authoritarianism:

Jason Brownlee and others describe dynastic authoritarian regimes as those where power is consolidated not just around a leader, but also through familial and kinship networks, facilitating the hereditary transmission of political authority. In such systems, the concentration of political capital within the family eases succession and mitigates elite fragmentation. Informal family appointments become mechanisms of governance and patronage networks are reinforced (Brownlee, 2007).

Electoral Authoritarianism:

Andreas Schedler’s concept of electoral authoritarianism refers to regimes that maintain formal electoral institutions while eliminating genuine electoral competition. These elections are neither free nor fair, and their outcomes are predetermined.

Uzbekistan's presidential and parliamentary elections from the mid-1990s onwards align closely with Schedler’s model. Karimov’s repeated “re-elections” with overwhelming majorities, the exclusion of real opposition, and tight state control over media illustrate the core characteristics of electoral authoritarianism (Schedler, 2013).

Hybrid Regimes:

Levitsky and Way, in their analysis of “competitive authoritarianism,” classify hybrid regimes as neither fully authoritarian nor democratic. Although democratic institutions exist, they operate under conditions of extreme inequality and manipulation.

The post-2016 period under Shavkat Mirziyoyev fits this model. Partial liberalization of the media, the release of some political prisoners, and steps toward economic liberalization create the appearance of openness. However, political pluralism remains tightly constrained and genuinely independent institutions have not emerged. As Levitsky and Way argue, such regimes often employ reformist rhetoric merely to ensure regime durability (Levitsky & Way, 2010).

Authoritarian Modernization:

Heydemann and others describe authoritarian modernization as a strategy wherein authoritarian regimes implement economic and administrative reforms to ensure their survival without introducing political pluralism. This approach embraces market reforms while maintaining authoritarian political structures (Heydemann, 2007).

Uzbekistan’s trajectory since 2016 fits this pattern. While the Mirziyoyev regime has focused on economic modernization and improving the investment climate, the core structure of political power—centered on centralized and authoritarian control—remains unchanged. Reforms such as enhancing professional governance, introducing e-government technologies, and bureaucratic restructuring represent key components of authoritarian modernization (Spechler & Spechler, 2020; McGlinchey, 2021).

These five theoretical approaches explain the evolution of authoritarianism in Uzbekistan across different stages:

- Personalist authoritarianism elucidates the political structures of the Karimov era and the regime’s reliance on the individual leader for continuity.

- Dynastic authoritarianism explains the establishment of familial rule through the appointment of Mirziyoyev’s daughter to a senior governmental position.

- Electoral authoritarianism highlights how elections functioned as tools of legitimacy both in the early years of the Karimov regime and under Mirziyoyev’s leadership.

- Hybrid regimes and competitive authoritarianism help unpack the nature and limitations of the reformist rhetoric that emerged after 2016.

- Authoritarian modernization explains the implementation of economic and technocratic reforms without expanding political freedoms.

The synthesis of these theoretical perspectives provides a complex and effective analytical framework for understanding political dynamics and regime resilience strategies in transitional systems such as Uzbekistan.

Historical Roots: The Era of Islam Karimov (1991–2016)

The formation of Uzbekistan’s political regime and its authoritarian character are closely linked to Islam Karimov’s rise to power and the institutional engineering implemented during his rule. This period can be seen as a classical example of post-Soviet authoritarianism, marked by personalist rule, a strengthened repressive apparatus, and regional-clan governance.

Building a Personalist Regime: The 1992 Constitution and Presidential Powers: Although the 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Uzbekistan formally invoked democratic state principles, in practice, it reinforced the legal foundation of a strong presidential system. The constitution granted the president extensive powers, including the authority to dissolve parliament. This reflects Barbara Geddes’s definition of personalist regimes, where institutional checks are subordinated to the will of the leader.

Karimov exploited these powers to remove political rivals, strengthen control over the media, and gradually construct a fully centralized authoritarian regime. He declared victories in the 1991, 2000, 2007, and 2015 presidential elections—elections held in accordance with the logic of electoral authoritarianism. These were widely criticized by international observers (OSCE/ODIHR, 2000; 2015).

Formality and Dysfunctionality of Political Institutions: Despite the existence of parliament, political parties, and the judiciary under Karimov, these institutions lacked genuine political power. Political parties such as the People's Democratic Party and the Liberal Democratic Party functioned as “loyal opposition” structures under state control. All elections featured uncompetitive and managed candidates, rendering political pluralism purely cosmetic (Olcott, 2005; Fumagalli, 2007).

The Oliy Majlis (Supreme Assembly) lacked real legislative authority, and most legislation was initiated by the presidential administration. This corresponds with Schedler’s description of “non-transparent competition” and “dysfunctional institutions” within electoral authoritarian regimes.

The Repressive Apparatus: National Security Service and the 2005 Andijan Events: One of the pillars of Karimov’s regime was the National Security Service (SNB), which operated with near-complete autonomy. It carried out widespread surveillance, repression, and coercion against both real and potential opposition. According to human rights organizations, thousands of people were imprisoned during this period under accusations of “religious extremism,” and independent journalists and rights defenders were subjected to intimidation and persecution (Human Rights Watch, 2004).

The 2005 Andijan massacre—where hundreds of civilians were killed—marked the climax of the regime’s repressive policy. While the government framed the event as an “Islamist uprising,” international observers assessed it as the violent suppression of peaceful protests (International Crisis Group, 2005). The event revealed the authoritarian essence of the regime and led to a dramatic deterioration of relations with the West.

Censorship, Informal Ideology, and Legitimacy Strategies: The ideological sphere in Uzbekistan was strictly controlled. State media amplified the cult of the leader, and foreign media were heavily restricted. The so-called “Uzbek Model”—an ideological framework emphasizing development based on national specifics, gradual transition, social stability, and a central role for the state—served as a tool for regime legitimation (Bohr, 2004).

Through this ideological model, the regime justified its detachment both from the Soviet legacy and from the perceived “dangerous influences” of Western liberalism. Legitimacy was built on authoritarian stability and the concept of national sovereignty (Turaeva, 2012).

Elite Management and Regional-Clan Balancing: Karimov’s personalist rule was also characterized by balancing regional and clan-based elite interests. Power-sharing and rotation of posts among elites from Fergana, Samarkand, and Tashkent ensured internal regime stability (Collins, 2006). These informal elite networks—based on family, region, or ethnicity—played a crucial role in decision-making.

Although Karimov was closely associated with the Samarkand clan, he maintained a careful balance with other regional groups to consolidate his long-standing rule. This reflects a variant of personalist authoritarianism compatible with elite-based governance (Radnitz, 2010).

As a result, Karimov’s rule represents a textbook case of personalist authoritarianism in Uzbekistan. During this period, repression, ideological control, and clan politics were central to the regime’s survival, and these institutional patterns left a lasting legacy for the post-Karimov era.

Foreign Policy and Authoritarian Behavior in the International Arena

Under Karimov, Uzbekistan’s foreign policy followed a strategy of pragmatic neutrality, sovereignty-based self-defense, and balanced diplomacy—characteristic of post-Soviet authoritarian regimes. His foreign policy served both to secure international legitimacy and to safeguard the continuity of the internal authoritarian regime. Relations with international partners were managed to minimize external pressure and limit foreign interference.

“Sovereign Authoritarianism” and Engagement with the West: In the late 1990s and especially after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the U.S. and the EU sought closer cooperation with Uzbekistan. As part of Washington’s “war on terror,” Uzbekistan allowed the U.S. to establish a military base in Karshi-Khanabad. This enhanced the regime’s international legitimacy and brought in economic assistance (Cooley, 2012). However, following Western condemnation of the Andijan massacre in 2005, Karimov closed the U.S. base and drastically reduced ties with the West. This was a clear demonstration of “sovereignty-centered authoritarianism”: a harsh response to attempts to intervene in domestic affairs.

As Schedler noted, electoral authoritarian regimes tend to deploy “masking” and “deflection” strategies when facing international monitoring and enforcement (Schedler, 2006). In Uzbekistan, this manifested initially as a “masking” strategy and later as a full retreat from engagement.

Authoritarian Consensus with Russia and China

Against the backdrop of deteriorating relations with the West, the Karimov regime turned toward Russia and China. Bilateral agreements and cooperation within the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) solidified this alignment, which provided both economic investment and political support for authoritarian governance (Ambrosio, 2009).

Geopolitical Balancing and the Turkmen Analogy

Karimov also pursued a cautious and balanced regional policy. While cooperation with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan was stable, relations with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan were often tense. Like Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan in the 1990s and 2000s adopted a quasi-isolationist model of authoritarianism premised on strong sovereignty (Kendzior, 2014). This posture served as a buffer against regional interventions and protected the regime from external legitimacy challenges.

All these factors indicate that the Karimov regime pursued a comprehensive strategy aimed at preserving stable authoritarianism both domestically and internationally.

First Phase of the Mirziyoyev Era (2016–2020): Environmental Changes in Authoritarianism

One of Mirziyoyev’s earliest and most symbolic moves was the restructuring of the National Security Service (SNB). The dreaded SNB was replaced in 2018 by the State Security Service (SSS), and its long-time head, Rustam Inoyatov, was removed (ICG, 2018). This marked the beginning of a personal consolidation of power and a symbolic recalibration of repressive governance.

However, the new agency was not brought under full civilian oversight nor subjected to accountability. The repressive apparatus was simply reformatted and equipped with more modern, flexible tools (Putz, 2019).

Currency and Banking Reforms

One of the most notable economic reforms was the liberalization of the national currency in 2017. The gap between the official and black-market exchange rates was eliminated, and currency exchange was deregulated. The banking sector was opened to more foreign investment, and measures to increase transparency in credit markets were introduced (World Bank, 2019).

These steps are emblematic of authoritarian modernization: strengthening technocratic economic management and investor confidence without altering the political regime (Laruelle, 2020).

Relative Media Openness and Tolerance of Criticism

At the beginning of the Mirziyoyev era, limited media liberalization was observed. Independent news portals emerged, and government officials occasionally responded to online criticism. The president himself publicly encouraged officials to be open to criticism and promoted public oversight.

However, this opening was quickly constrained within a framework of selective tolerance: systemic and politically grounded criticism was met with intimidation, legal persecution, and imprisonment (Human Rights Watch, 2021). This signaled a return of masked electoral authoritarianism.

Public Opinion and Reactive Policy-Making

Public opinion began to play a more visible role in the government’s decision-making process. Public surveys, digital complaint portals (such as the “Virtual Reception Office”), and social feedback mechanisms influenced some policy adjustments (Lemon, 2019). This aimed to introduce reactive governance and bolster social legitimacy.

Nevertheless, the president and his inner circle remained the main decision-makers, and the system did not allow for institutionalized collective decision-making. These were procedural, not structural changes.

Structural Reforms and Constitutional Changes (2020–2024)

A 2023 constitutional referendum extended the presidential term from five to seven years and reset term limits, allowing Mirziyoyev to run for a third term. This resembled the “constitutional reset” practice seen in countries like Azerbaijan (Pannier, 2023).

While officially framed as reflecting the “will of the people,” the process lacked genuine debate and viable alternative campaigns. This represents a renewal of personalist authoritarianism and a consolidation of “reformist authoritarianism.”

Cosmetic Electoral Reforms and De Facto Non-Competition

Although some formal electoral changes were introduced—such as gender quotas in municipal elections and digital voting procedures—competitive electoral conditions were not established. Real opposition parties were systematically denied registration (Freedom House, 2024). The Liberal Democratic Party and other “loyal opposition” groups fully supported Mirziyoyev’s political agenda, illustrating the hybrid regime features described by Levitsky and Way: real authoritarian continuity under the facade of pluralism.

Technocratization and Digitalization of State Governance

New technocrats rose to prominence in state administration, and digital services, e-government tools, and open data platforms were implemented. The reduction of bureaucratic barriers, especially in public services, and the digitalization of citizen–state interactions became priorities (ADB, 2023).

Yet this technocratic modernization did not undermine the authoritarian structure of the regime. In other words, technical modernization did not translate into political liberalization.

Unchanged Environment for NGOs and Independent Media

Despite partial permissions for some NGOs and independent media outlets, no fundamental shift occurred. Bureaucratic barriers to NGO registration remained, and human rights organizations continued to operate under strict oversight (Amnesty International, 2023). This reflects the enduring repressive elements of electoral authoritarianism.

The reforms undertaken during Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s tenure are characterized by limited structural changes, technocratic renewal, and adaptive repression. The regime retains its authoritarian nature while presenting itself as more flexible, modern, and responsive to public opinion. This aligns closely with Heydemann’s model of “authoritarian modernization.”

Authoritarian Resilience and Paradoxes

The modernization efforts undertaken in Uzbekistan since 2016 have revealed a paradoxical trajectory: on one hand, they reflect the technical enhancement of the state's governance capacity; on the other, they have preserved the authoritarian structure and personalist centralization of power. In this sense, Uzbekistan’s development model exhibits both change and continuity. This section explores the main paradoxes of this duality and their theoretical interpretations.

Sources of Regime Stability: Personalization and Repressive Adaptation

Research on authoritarian regime durability suggests that personalist regimes build their stability on strong leader cults, institutional weakness, and the flexibility of their repressive apparatus (Svolik, 2012). Although Mirziyoyev has adopted a more pragmatic and flexible leadership style compared to his predecessor, the political system remains centralized and dependent on the individual leader.

At the same time, the repressive apparatus has not been dismantled but transformed—from “hard repression” to a mode of “selective and preventive control” (Lemon, 2019). This shift shows that repression has become a more efficient and cost-effective tool of authoritarian governance.

The Contradiction Between Modernization and Authoritarian Stability

Heydemann’s theory of authoritarian modernization demonstrates that economic and administrative modernization does not necessarily accompany political liberalization. In Uzbekistan, technocratic reforms such as digitalization, currency liberalization, the establishment of technoparks, and improved public services have been implemented. However, these reforms lack the components of political inclusivity and the rule of law.

This contradiction can be explained by the fact that modernization serves not as a pathway to regime transformation, but as a mechanism for reinforcing regime durability and securing international legitimacy (Burnell & Schlumberger, 2010).

Elite Stability and Clan–Regional Regulation

The regional-clan balancing mechanisms of the Karimov era have been preserved in a modified form under Mirziyoyev. Although he has formed new elite groups around himself, these changes remain personalized rather than structural. The previous elite networks have simply been rotated or adjusted within the system (Eshonkulov, 2021).

A New Stage of Familial Consolidation: The Appointment of Saida Mirziyoyeva

In 2025, the appointment of President Mirziyoyev’s daughter, Saida Mirziyoyeva, as the head of the Presidential Administration marked a new institutional turning point in Uzbekistan’s authoritarian evolution. This event illustrates how authoritarian modernization is evolving in parallel with familial-political consolidation, increasing the likelihood of a dynastic political succession.

That such an appointment occurred during an ongoing period of formal reform rhetoric indicates that Heydemann’s concept of authoritarian modernization is no longer limited to technocratic or administrative spheres. Instead, regime legitimacy and stability are now also being structured through intra-familial and clan-based appointments. This suggests the restoration of personalist authoritarianism in the form of dynastic personalism in post-Karimov Uzbekistan.

Saida Mirziyoyeva’s appointment can be interpreted as the early stage of what is referred to in the literature as “dynastic succession.” As Barbara Geddes has noted, personalist regimes often resort to the inclusion of family members in order to preserve long-term control (Geddes, 2003b). In the context of Uzbekistan, this appointment can be viewed as the formalization of a political succession structure.

This development also exposes the growing dualism between formal reforms and informal familial power. Thus, Saida Mirziyoyeva’s appointment stands as an important empirical example indicating that authoritarian modernization is shifting away from institutional transformation and toward familial political adaptation.

International Context and Authoritarian Learning

The Mirziyoyev regime seeks to maintain a balanced foreign policy with both Western countries and authoritarian powers such as Russia and China. Although symbolic steps have been taken to project a reformist image internationally, these actions have not resulted in any meaningful weakening of domestic political monopoly.

Such behavior reflects the logic of authoritarian learning: regimes observe and emulate one another’s experiences in consolidating stability within the framework of controlled reforms (Way, 2015). Uzbekistan has followed the precedent set by countries like Azerbaijan and Russia, combining cosmetic reforms with entrenched authoritarianism.

In summary, the transformation of authoritarianism in Uzbekistan is characterized more by changes in form than in substance. Modernization and technocratic reforms do not proceed alongside political liberalization; rather, they serve to rejuvenate the regime. This reinforces the conclusion that deep institutional reforms are necessary for genuine political change.

In this context, Uzbekistan may be understood as a symbiosis of electoral, personalist, and dynastic authoritarianism: on one hand, the system selectively renews itself; on the other, it deepens informal mechanisms to preserve political monopoly.

Conclusion

The evolution of authoritarianism in Uzbekistan has occurred in two major phases. The first phase, from 1991 to 2016, was marked by the establishment of a repressive personalist regime under Islam Karimov. During this period, the mechanisms of state control were exercised through harsh repression.

The second phase began with the rise of Shavkat Mirziyoyev and has been characterized by intensified institutional control and technocratic modernization efforts. His reforms—particularly the introduction of digital governance and partial openness in certain socio-political sectors—have increased the regime’s adaptive capacity.

However, the findings of this study show that these modernization reforms have not resulted in fundamental political transformation or the foundational changes necessary for democratic transition. The regime continues to maintain political monopoly while preserving formal institutions, and severe constraints remain in place regarding elections, media freedom, and elite structure.

The case of Uzbekistan offers important insights for the analysis of authoritarian stability and transformation potential in Central Asia. It illustrates how authoritarian regimes adapt and how formal democratic elements and technocratic reforms can be instrumentalized to reinforce authoritarian durability.

References:

- Lewis, D. (2008). "The Dynamics of Regime Change: Domestic and International Factors in the Rise and Fall of Authoritarianism." Europe-Asia Studies, 60(9), 1557–1575.

- Matveeva, A. (2009). "Legitimising Central Asian Authoritarianism: Political Manipulation and Symbolic Power." Europe-Asia Studies, 61(7), 1095–1121.

- Anceschi, L. (2020). Analysing Power in Post-Soviet Central Asia: A Conceptual Framework. Routledge.

- Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

- Schedler, A. (2006). Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Heydemann, S. (2007). "Upgrading Authoritarianism in the Arab World." Brookings Institution.

- Cooley, A. (2012). Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press.

- Geddes, B. (2003a). Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics. University of Michigan Press.

- Frantz, E. (2014). Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions: A New Data Set. Perspectives on Politics, 12(2), 313–331.

- Brownlee, J. (2007). Authoritarianism in an Age of Democratization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schedler, A. (2013). The Politics of Uncertainty: Sustaining and Subverting Electoral Authoritarianism. Oxford University Press.

- Levitsky, S., & Way, L. A. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press.

- Heydemann, S. (2007). Upgrading Authoritarianism in the Arab World. Brookings Institution.

- Spechler, M. C., & Spechler, D. R. (2020). Uzbekistan: The New Face of Authoritarian Modernization. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 53(4), 100–113.

- McGlinchey, E. (2021). Mirziyoyev’s Uzbekistan: Democratization or Authoritarian Modernization? PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo, No. 662.

- OSCE/ODIHR. (2000; 2015). Election Observation Reports: Uzbekistan Presidential Elections.

- Olcott, M. B. (2005). Central Asia’s Second Chance. Carnegie Endowment.

- Fumagalli, M. (2007). Informal Politics in Uzbekistan: Clan, Region and Regime. International Journal of Middle East Studies, 39(2), 271–293.

- Human Rights Watch. (2004). Creating Enemies of the State: Religious Persecution in Uzbekistan. HRW Reports.

- International Crisis Group. (2005). The Andijan Uprising: What Happened and What It Means. Asia Briefing No. 38.

- Bohr, A. (2004). Uzbekistan: Politics and Foreign Policy. Royal Institute of International Affairs.

- Collins, K. (2006). Clan Politics and Regime Transition in Central Asia. Cambridge University Press.

- Radnitz, S. (2010). Weapons of the Wealthy: Predatory Regimes and Elite-Led Protests in Central Asia. Cornell University Press.

- Cooley, A. (2012). Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press

- Schedler, A. (2006). Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Lynne Rienner.

- Ambrosio, T. (2009). Authoritarian Backlash: Russian Resistance to Democratization in the Former Soviet Union. Ashgate Publishing.

- Kendzior, S. (2014). The Uzbek Paradox: Authoritarianism and Economic Liberalism in Post-Soviet Central Asia. Global Affairs Journal.

- ICG. (2018). Uzbekistan: Reform or Repeat? International Crisis Group Report No.

- Putz, C. (2019). “Security Services in Uzbekistan: Continuity and Change”. The Diplomat.

- World Bank, 2019. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uzbekistan

- Laruelle, M. (2020). The Return of the “Uzbek Model”? Authoritarian Resilience in Central Asia. PONARS Eurasia Memo.

- Human Rights Watch. (2021). Uzbekistan: Media Under Pressure.

- Lemon, E. (2019). Authoritarian Innovations in Central Asia. Central Asian Affairs, 6(1), 1–25.

- Pannier, B. (2023). “Uzbekistan’s New Constitution: Old Tricks in New Packaging”. RFE/RL.

- Freedom House. (2024). Nations in Transit: Uzbekistan.

- 250.ADB. (2023). Digital Governance in Central Asia. Asian Development Bank.

- Amnesty International. (2023). Uzbekistan 2023 Human Rights Review.

- Geddes, B. (2003). Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics. University of Michigan Press.

- Svolik, M. (2012). The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge University Press.

- Burnell, P., & Schlumberger, O. (2010). Promoting Democracy – Promoting Autocracy? International Politics and National Political Regimes. Contemporary Politics, 16(1), 1–15.

- Eshonkulov, B. (2021). Elite Realignments and Informal Networks in Post-Karimov Uzbekistan. Central Asian Survey, 40(3), 410–429.

- Geddes, B. (2003b). Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research

43. Way, L. A. (2015). The Limits of Autocracy Promotion: The Case of Russia in the ‘Near Abroad’. European Journal of Political Research, 54(4), 691–706.