The first part of the article is available here: Click

---

In March 2019, with the unexpected resignation of Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan witnessed—for the first time in its history—a peaceful and formal transfer of power. However, this process was limited to formal changes only. Nazarbayev retained the title of Elbasy (Leader of the Nation) and continued to exert influence over the country’s power structures through his chairmanship of the National Security Council and several informal channels. This transition remained deeply embedded in the existing clan-based power networks. While Kassym-Jomart Tokayev assumed power and labeled the process a “soft transfer,” it was still dominated by previous elite factions.

The reforms introduced under Tokayev’s presidency—particularly the constitutional amendments in 2022—were aimed at reducing presidential powers and strengthening the roles of parliament and local governance. Nevertheless, analysts largely regard these changes as symbolic, since the real centers of power, including the Nazarbayev clan, continued to hold significant informal influence.

The violent events of early January 2022—triggered by a sharp increase in liquefied gas prices—were indicative of a much deeper political crisis. Tokayev responded harshly to these protests by inviting Russian peacekeepers from the CSTO, revealing the authoritarian nature of the regime and its reliance on coercive institutions to manage dissent.

As emphasized in this introduction, the 2019–2025 period is characterized by formal reforms balanced against clan-dominated power structures and entrenched authoritarian institutions. The following analysis explores this transitional phase in depth, covering political transformation and broader economic developments.

The Transition Period: From Nazarbayev to Tokayev (2019–2025)

Formal Transfer and Limited Transformation: In March 2019, the sudden resignation of Nursultan Nazarbayev from long-term presidency and the peaceful handover of power to another individual introduced a new dynamic to post-Soviet authoritarianism (BBC News, 2019). As Schatz notes, Nazarbayev’s resignation represented a “formal transformation,” in which institutional changes were limited, and the core political and administrative structures remained largely intact. Tokayev’s ascension to the presidency occurred within a maze of formal and informal mechanisms, where the “traditional governance” model—namely the influence of Nazarbayev’s clan—remained the actual source of power (Schatz, 2021).

Some constitutional reforms were implemented under Tokayev’s leadership. In June 2022, presidential powers were formally curtailed, and the roles of parliament and the government were enhanced (OSCE, 2022). However, the depth of these reforms and whether they signaled a departure from authoritarianism remains a matter of debate (Freedom House, 2023a). Analysts argue that these changes were largely reactive in nature (Kassenova, 2023a).The 2022 Protests and Political Fragmentation: The mass protests and demonstrations of January 2022 became the most serious socio-political upheaval in Kazakhstan’s post-independence history (Reuters, 2022). While the immediate cause was public discontent over the dramatic rise in liquefied gas prices, the events revealed underlying structural grievances—deepening social stratification, systemic corruption, political repression, and the prolonged delay of democratic reforms (International Crisis Group, 2022).

The protests were not only directed against the government but also targeted Nursultan Nazarbayev and the political system he had created. Demonstrators openly challenged Nazarbayev’s symbolic political dominance and the oligarchic networks associated with his family by chanting slogans such as “Shal ket!” (“Old man out!”). This marked a symbolic end to Nazarbayev’s hegemonic role in political life and led to his removal from the chairmanship of the National Security Council (Cooley, 2022).

As the protests escalated in scale and violence spread to several cities, the government hardened its response. Security forces—including the National Security Committee, internal affairs agencies, and the military—cracked down violently on demonstrators. Dozens were killed, thousands were detained, and international concern over human rights violations increased (Freedom House, 2023b).

These events further deepened political fragmentation in the country and severely undermined the legitimacy of President Tokayev’s rule. At the same time, they triggered a re-evaluation of Nazarbayev’s political legacy and created opportunities for Tokayev to adopt a more distinct “reformist” image.

“New Kazakhstan”: Reality and Symbolism

Following the protests, President Tokayev introduced a package of reforms under the slogan “New Kazakhstan.” Within this framework, reforms were announced regarding press freedom, separation of powers, and changes to the electoral system (OSCE, 2023).

Symbolic changes also became part of this reform process. Notably, the 2019 renaming of the capital from Astana to Nur-Sultan in honor of Nazarbayev had not been met with public consensus. Following the January events and growing public dissatisfaction with Nazarbayev, Tokayev initiated the restoration of the capital’s original name—Astana—in September 2022. This step, in symbolic terms, marked the end of the Nazarbayev era.

However, academic literature and international reports stress that the majority of these reforms were largely formal in nature (Kassenova, 2023b). Structural changes were mostly limited to the visible redistribution of authority, and under Tokayev’s leadership, a new, more technocratic authoritarian model is emerging. Unlike Nazarbayev’s personalist, leader-based model, Tokayev’s era speaks in the language of institutional reform and legality, yet genuine political pluralism has still not materialized.

Analysis

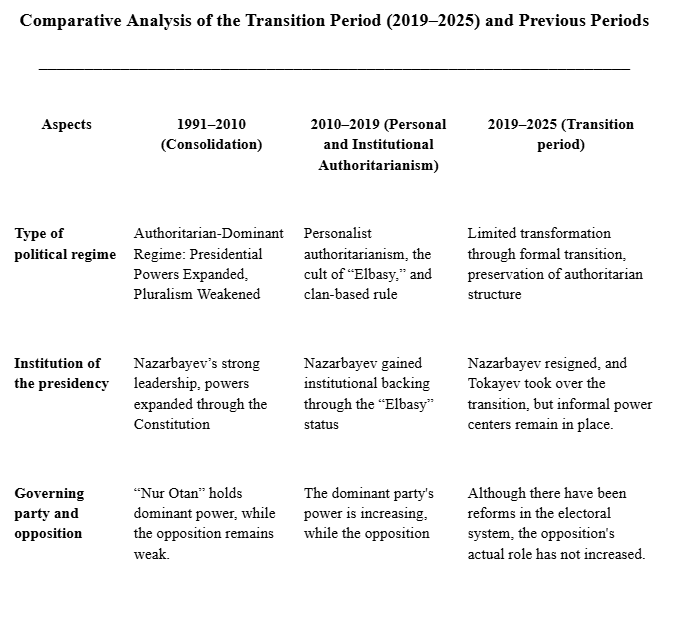

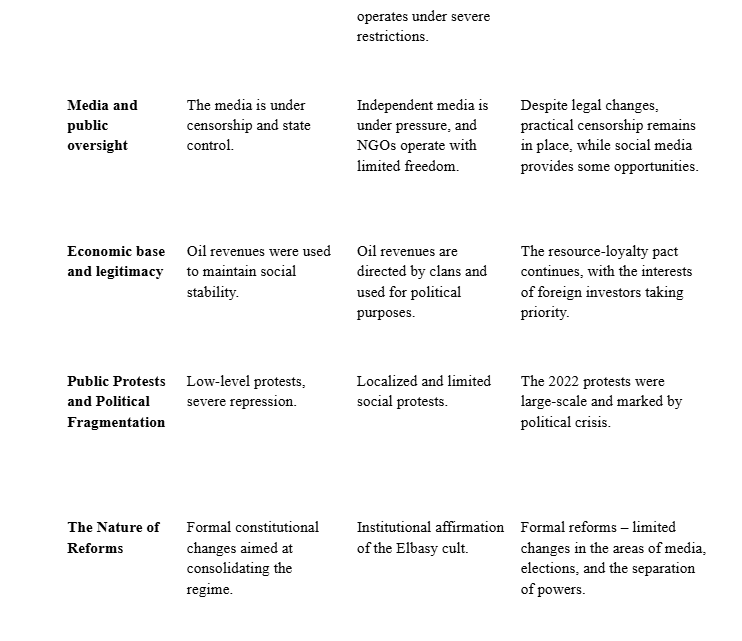

Stability and Transformation of the Political Regime: The period from 1991 to 2010 was primarily characterized by the formation and consolidation of an authoritarian regime in Kazakhstan. During this phase, the institution of the presidency became increasingly centralized, and state institutions operated under the influence of the political leader (Schatz, 2004). From 2010 to 2019, the regime evolved into a more personalized system, with Nazarbayev attaining both symbolic and real power through the status of Elbasy (Kassenova, 2011). In the period of 2019–2025, while formal political structures persisted, actual shifts in the balance of power and institutional transformation remained minimal (Freedom House, 2023).

Public Oversight and the Role of the Media: Between 1991 and 2010, the media operated under strict state control. In 2010–2019, censorship intensified and pressure on NGOs increased. In the 2019–2025 period, although reforms related to press freedom were introduced at the legislative level, in practice, independent journalists and activists continued to face significant pressure. Social media and information technologies provided limited opportunities for freedom of expression, yet strong state control persists (OSCE, 2023).

Intensity and Management of Public Protests: In earlier periods, public protests were either limited or suppressed with force. However, the January 2022 protests were large-scale and significantly undermined the stability of the political regime. These events demonstrated the regime’s readiness to respond to crises with coercive and forceful measures (Reuters, 2022).

The Nature and Depth of Reforms: While constitutional reforms were carried out both in the 1991–2010 and 2019–2025 periods, the former served primarily to consolidate authoritarianism. In the current phase, despite some liberal-leaning initiatives, the reforms are largely symbolic and have not altered the fundamental nature of the governing structure.

Conclusion: The evolution of authoritarian governance in Kazakhstan during the transitional period (2019–2025) was accompanied by formal reforms, but the persistence of entrenched power structures and informal centers of influence indicates the continuation of authoritarian rule. This phase illustrates a delicate balance between stability and risk domestically, while simultaneously highlighting Kazakhstan’s unique transitional model among regional authoritarian systems.

Post-2019: Political Transformation and a New Phase of Authoritarianism

Post-Nazarbayev Period: Although Nursultan Nazarbayev’s resignation in March 2019 after three decades in power was framed as a “soft transfer” of authority, he retained his Elbasy status and continued to exert political influence through his role as Chairman of the National Security Council. During the transition to Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s presidency, messages of reform and stability were conveyed, yet the balance of power among authoritarian institutions, political clans, and power centers remained unchanged (FPRI, 2022).

Reforms and the Illusion of Liberalization: Political reforms introduced under Tokayev were largely aimed at improving Kazakhstan’s international image and reducing internal pressures. While some relaxation was observed in electoral legislation and NGO activity, genuine political competition remained formal. The opposition continued to face severe restrictions, and media remained under state control (AP News, 2023).

Social Discontent and Political Reactions: The large-scale protests that erupted in January 2022 were met with violent repression, including a government-issued “shoot to kill” order. In an effort to suppress civic activism, Kazakhstan invited the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)—effectively the Russian military—for intervention (Time, 2022). This event, known as "Bloody January," resulted in 238 deaths, thousands of arrests, and numerous allegations of torture (Le Monde, 2024).

New Authoritarian Dynamics and Regime Strategies: A new era has emerged featuring “overt authoritarianism” — where formal democratic institutions are preserved while technological surveillance systems, social media restrictions, and information manipulation have expanded (Chatham House, 2023). Electoral and administrative reforms have created an image of public engagement, though these steps remain largely symbolic.

Regional Context and the Future of Kazakhstan’s Authoritarian Model: Kazakhstan’s political model is heavily influenced by both Russia and China. The CSTO’s intervention reshaped regional equilibrium and influenced Kazakhstan’s multivector foreign policy. Nevertheless, the regime’s core vulnerabilities lie in its weak economic diversification, persistent social discontent, and failure to advance democratic liberalization.

The political system formed in Kazakhstan post-2019 continues to reflect a form of institutional authoritarianism centered on individual leadership. The regime attempts to maintain its continuity by balancing between repressive and inclusive strategies.

Post-2019: Socio-Economic Aspects and the Role of Society

Economic Transformation and the Authoritarian Regime: Since 2019, Kazakhstan’s economy remains reliant on the oil and gas sector, with the resource-based model maintaining dominance. Public declarations around economic diversification and the “Kazakhstan–2050” strategic plan are largely aimed at signaling reform intentions to domestic and international audiences. However, control over economic resources remains in the hands of oligarchic structures and political clans, and corruption-driven profit distribution limits any meaningful impact on broader social welfare. Although the legitimacy of resource-derived income continues, fluctuations in global oil markets threaten the regime’s economic resilience. In response, the government increasingly prioritizes loyalty-based policies and tighter control, despite discussions of reform (Transparency, 2024).

Social Stratification and the Political Role of Society: Kazakhstani society faces growing concerns about socio-economic inequalities, limited opportunities for political participation, and human rights abuses. Political activism is on the rise, especially among urban residents and youth, yet the state responds with tight restrictions (Freedom House, 2019).

Access to foreign education and open information flows have helped to spread democratic values and demands for transparency among the younger generation. The regime perceives this as a threat and intensifies control over social media (Asia Global Affairs, 2022). At the same time, troll networks, censorship strategies, and state media resources are used to limit independent thinking (Voices Central Asia, 2019).

The Role of Society and Future Prospects: Society’s role in Kazakhstan’s political transformation remains limited, but growing social discontent and protests compel the regime to adopt certain inclusive measures (Foreign Policy, 2021). Nonetheless, a well-organized opposition has yet to emerge. The state manages society through a combination of behavioral regulation and technological surveillance, indicating that authoritarian culture remains deeply rooted (Freedom House, 2024).

The Durability of Authoritarianism and Future Prospects

The durability of authoritarianism in Kazakhstan is not accidental. It is underpinned by specific internal mechanisms, regional dynamics, geopolitical positioning, and socio-psychological factors that contribute to the regime’s adaptability and resilience. However, this durability is neither permanent nor absolute—both internal and external developments may challenge the model’s stability.

1. Internal Mechanisms of Durability

Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime has been reinforced by several internal factors:

- Political apathy and consent for stability:

Post-Soviet trauma and political passivity among the population have led to a preference for authoritarian stability over democratic uncertainty. The regime manipulates this mindset by popularizing the narrative that “freedom brings chaos” (Laruelle, 2015). - Rentier economy and temporary welfare:

Oil and gas revenues enabled the state to offer limited social transfers to suppress public discontent, creating a form of “authoritarian social contract” — minimal welfare in exchange for political passivity (Luong & Weinthal, 2020). - Repression and selective liberalization:

Rather than mass repression, the regime favors targeted and selective pressure, maintaining a climate of fear while avoiding international backlash. Simultaneously, it implements controlled liberal reforms to defuse internal tensions (Silitski, 2025).

2. External Factors and Geopolitical Resilience

Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime is closely tied to its regional and international environment:

- Russia and China as strategic partners:

Russia remains central to Kazakhstan’s security and energy strategies, and Moscow’s open support for authoritarianism helps legitimize this model. Meanwhile, China’s non-interference principle regards Kazakhstan’s internal stability as essential to its own border security (Cooley, 2012). - Weak international pressure and double standards:

Western states often pursue softer policies toward Kazakhstan due to energy and security interests. Despite the country’s failure to adhere to democratic standards, it is still treated as a strategic partner — granting the regime a degree of international legitimacy (Freedom House, 2023).

3. Potential for Transformation and Emerging Risks

The stability of authoritarianism may diminish over time due to:

- Collapse of the mono-resource economy:

Declining energy prices, weakening of the oil-dependent economy, and unequal income distribution could fuel rising public dissatisfaction and undermine the implicit social contract. - Social and demographic change:

The younger generation, raised in an environment of greater information access, is less aligned with authoritarian values. Urbanization and rising education levels may foster a more active and demanding civil society (Melvin, 2018). - Fragmentation of elite and internal competition:

Tokayev’s attempts to diminish the Nazarbayev clan’s influence may increase tensions within the political system, potentially destabilizing it and creating openings for transformation. - Security risks and legitimacy crises:

The January 2022 protests showed that socio-economic grievances and political pressure can trigger mass mobilization. Repetition of such events and further repression may severely damage the regime’s legitimacy.

Currently, Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime appears stable in the short term. However, this stability rests on a fragile balance shaped by internal repression, ideological manipulation, and strategic external alliances. Economic shocks, social transformation, or regional instability could disrupt this balance and force the regime toward either genuine reform or heightened authoritarian control.

Conclusion

The evolution of authoritarianism in Kazakhstan has been shaped by the interplay between personalist leadership and institutional mechanisms. The institutionalization of Nursultan Nazarbayev’s Elbasy status and the central role of his political clan in maintaining and structuring power were key features of the authoritarian system. As Schatz notes, “clan politics” and kinship networks served as foundational elements of Kazakhstan’s political architecture, characterizing the country as a model of “modern clan politics” (Schatz, 2004). Kendzior adds that the institutionalization of the Elbasy model contributed to the internal and international legitimacy of Kazakhstan’s authoritarianism (Kendzior, 2019).

According to Freedom House’s analysis, the January 2022 protests gave some momentum to political reform; however, the continued marginalization of the opposition and the strength of the state apparatus have prevented these changes from resulting in meaningful democratization. In such regimes, where pluralism is permitted only formally, state control and repression remain the central pillars of authoritarian governance (Freedom House, 2023).

In comparative context, Levitsky and Way argue that Kazakhstan’s hybrid authoritarian model shares similarities with regimes in Russia and other Central Asian states, but the legalization of the Elbasy status added a unique institutional dimension to the Kazakhstani regime (Levitsky & Way, 2010). Ross, analyzing the role of oil in the national economy, emphasizes that in resource-loyalty pacts, oil revenues become a core component of the social legitimacy of authoritarian regimes (Ross, 2012).

Based on the works of Diamond and Schedler, it can be argued that if the reforms introduced under Tokayev result in the strengthening of real political institutions, Kazakhstan may evolve into a more mature and resilient hybrid regime (Diamond, 2002; Schedler, 2006).

Thus, the evolution of authoritarianism in Kazakhstan represents a synthesis of Nazarbayev’s personalist leadership cult and institutional mechanisms, producing both stability and uncertainty in the political system. The reforms and social unrest under Tokayev have yet to determine whether the country will continue along the path of hybrid authoritarian governance.

References:

- BBC News. (2019). Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev resigns after almost 30 years in power. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-47628854

- Schatz, E. (2021). The Making of a ‘Soft Authoritarian’ State in Kazakhstan. Post-Soviet Affairs, 37(5), 393–416.

- OSCE. (2022). Kazakhstan’s constitutional reforms: A step towards democratization? OSCE Reports.

- Freedom House. (2023)a. Freedom in the World 2023: Kazakhstan.

- Kassenova, N. (2023). Post-Nazarbayev Kazakhstan: Authoritarian Continuity or Change? Central Asian Affairs, 10(2), 134-157.

- Reuters. (2022). Kazakhstan unrest: What’s behind the protests? https://www.reuters.com/markets/currencies/stability-turmoil-whats-going-kazakhstan-2022-01-06/

- International Crisis Group. (2022). Kazakhstan’s January Crisis: Causes and Consequences.

- Freedom House. (2023)b. Freedom in the World 2023: Kazakhstan.

- Cooley, A. (2022). Authoritarian resilience and the ‘New Kazakhstan’. Journal of Democracy, 33(1), 95-109.

- OSCE. (2023). Election observation report: Kazakhstan parliamentary elections.

- Kassenova, N. (2023). Post-Nazarbayev Kazakhstan: Authoritarian Continuity or Change? Central Asian Affairs, 10(2), 134-157.

- Schatz, E. (2004). Modern Clan Politics: The Power of "Blood" in Kazakhstan and Beyond. University of Washington Press.

- Kassenova, N. (2011). Kazakhstan: Incremental Change or Stagnation? In: Countries at the Crossroads 2011, Freedom House.

- Freedom House (2023). Nations in Transit 2023: Kazakhstan

- OSCE (2023). OSCE Media Freedom Report on Kazakhstan. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

- Reuters (2022). Kazakhstan Protests: Dozens Killed, Government Buildings Torched. Reuters, January 2022.

- FPRI. (2022, March 7). How the Intervention in Kazakhstan Revitalized the Russian-led CSTO. Foreign Policy Research Institute.

- AP News. (2023, January 20). A year after Kazakhstan's deadly riots, questions persist. https://apnews.com/article/27777324a342490b737866449ca00f93

- Time. (2022, January). Kazakhstan Is Facing Its Most Dramatic Political Upheaval in 30 Years. https://time.com/6137439/kazakhstan-protests-russia/

- Le Monde. (2024, June 24). Victims of Kazakhstan’s ‘Bloody January’ long for justice. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2024/06/24/victims-of-kazakhstan-s-bloody-january-long-for-justice_6675593_4.html

- Chatham House. (2023, June 27). How to intervene symbolically: The CSTO in Kazakhstan. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2023/06/how-intervene-symbolically-csto-kazakhstan

- Eurasianet. (2022, January 6). CSTO agrees to intervene in Kazakhstan unrest. https://eurasianet.org/csto-agrees-to-intervene-in-kazakhstan-unrest

- Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index 2024: Kazakhstan. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2024/index/nzl

- Freedom House. (2019). Freedom on the Net 2019: Kazakhstan. https://freedomhouse.org/country/kazakhstan/freedom-net/2019

- Asia in Global Affairs. (2022, January 12). Social media and censorship in Kazakhstan. https://www.asiainglobalaffairs.in/Commentary/social-media-and-censorship-in-kazakhstan/

- Voices on Central Asia. (2019, March 4). #Hashtag activism: Youth, social media and politics in Kazakhstan. https://voicesoncentralasia.org/hashtag-activism-youth-social-media-and-politics-in-kazakhstan/

- Foreign Policy. (2021, July 12). Kazakhstan’s alternative media is thriving—and in danger. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/12/kazakhstan-alternative-media-thriving-danger/

- Freedom House. (2024). Freedom on the Net 2024: Kazakhstan. https://freedomhouse.org/country/kazakhstan/freedom-net/2024

- Laruelle, M. (2015). Kazakhstan in the Making: Legitimacy, Symbols and Power. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Luong, P. J., & Weinthal, E. (2010). Oil Is Not a Curse: Ownership Structure and Institutions in Soviet Successor States. Cambridge University Press.

- Silitski, V. (2005). "Preempting Democracy: The Case of Belarus." Journal of Democracy, 16(4), 83–97.

- Cooley, A. (2012). Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford University Press.

- Freedom House. (2023). Nations in Transit: Kazakhstan.

- Melvin, N. J. (2018). Authoritarianism and Youth in Central Asia. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- Schatz, E. (2004). Modern Clan Politics: The Power of "Blood" in Kazakhstan and Beyond. University of Washington Press. "The political landscape in Kazakhstan is deeply entrenched in clan networks that sustain the regime’s authority."

- Kendzior, S. (2019). The Anatomy of Autocracy: The Case of Kazakhstan. Problems of Post-Communism, 66(1), 45-56. "Nazarbayev’s cult of personality, institutionalized under the title ‘Elbası’, bolsters both domestic control and international legitimation."

- Freedom House. (2023). Freedom in the World 2023: Kazakhstan. "Despite some reform rhetoric, Kazakhstan remains an authoritarian regime with limited political freedoms and restricted civil society."

- Levitsky, S., & Way, L. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press. "Kazakhstan’s hybrid regime shares key traits with other post-Soviet autocracies, blending electoral processes with authoritarian control."

- Ross, M. L. (2012). The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations. Princeton University Press. "Oil wealth provides authoritarian regimes with resources to sustain social programs that legitimize their rule."

- Diamond, L. (2002). Elections without Democracy: Thinking About Hybrid Regimes. Journal of Democracy, 13(2), 21-35. "Hybrid regimes exhibit both democratic institutions and authoritarian practices, often leading to ambiguous political trajectories."

41. Schedler, A. (2006). Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Lynne Rienner Publishers.