Introduction

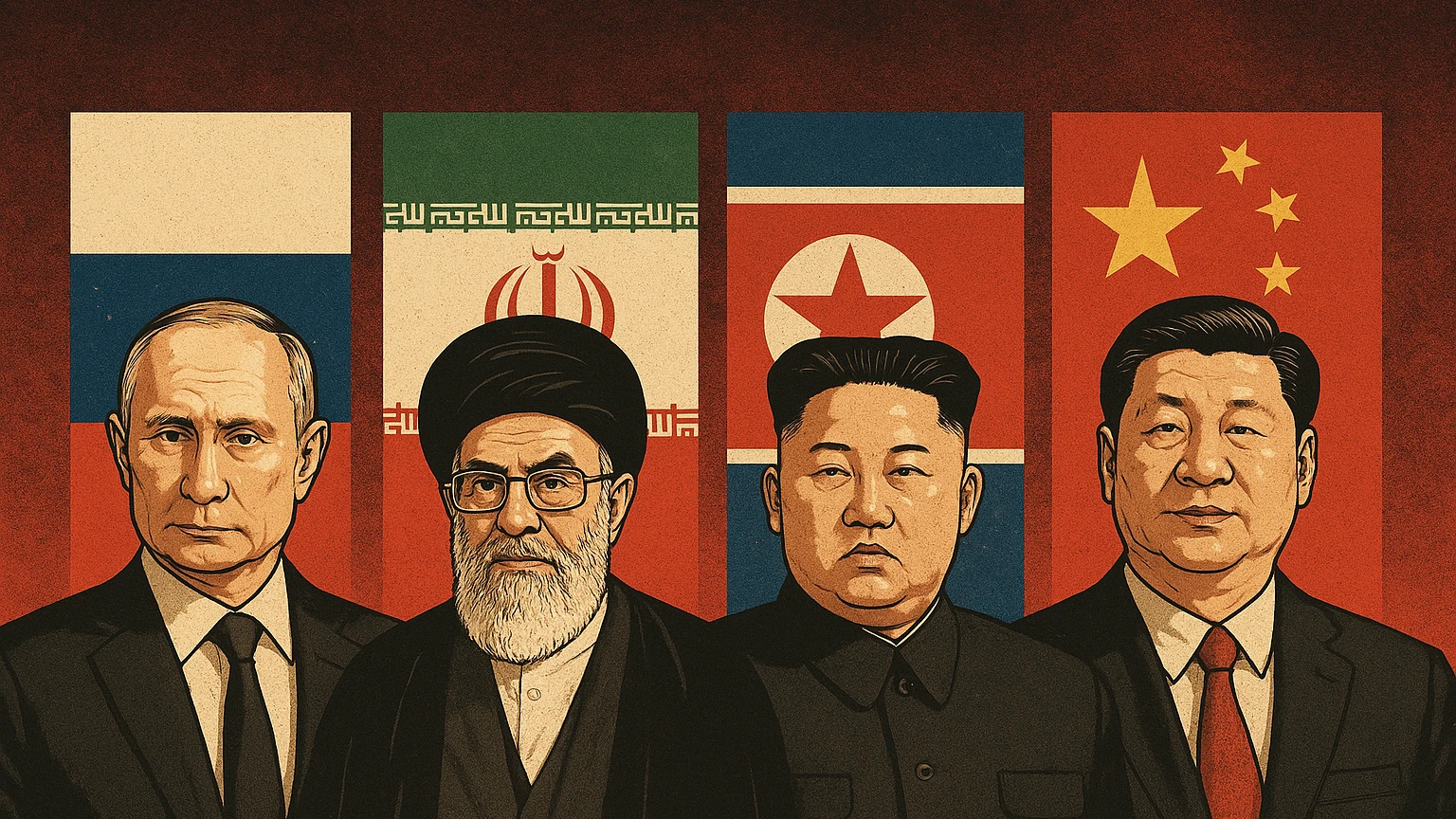

The deepening alliance among Russia, North Korea, Iran, and China is becoming an increasingly serious strategic threat to the West. This coalition, referred to as the “Axis of Authoritarianism,” has further strengthened its ties after Russia’s full-scale aggression against Ukraine (Carnegie Endowment 2024a).

Relations within this bloc of authoritarian regimes are complex and multifaceted. Their cooperation spans from trade and military fields (including arms sales, joint weapons production, and technological development projects) to space programs, cybersecurity, and intelligence data exchange (LLNL, 2025a), complemented by economic initiatives aimed at weakening the U.S.'s global financial dominance through dedollarization policies.

U.S. and European Union sanctions have failed to deter these countries from their aggressive policies. On the contrary, the process has resulted in Moscow becoming a symbol of “anti-Western resistance.” This image serves as an attractive model for some states (The Guardian 2024a).

Facing the largest war in Europe since 1945, Western democracies must take serious and systematic measures to ensure the continent’s security amid the possibility of a Russia–NATO confrontation in the coming decade.

The so-called “Quartet of Chaos” skillfully exploits loopholes in sanctions regimes and weaknesses in export control systems to sustain and expand its destabilizing activities. One of the gravest concerns is the continued discovery of Western-made components in weapons produced by Russia, Iran, and North Korea (ODNI, March 2025a). This fact demonstrates these regimes’ ability to adapt to and circumvent sanctions at both technological and logistical levels.

The main goal of this analysis is to systematically examine the structure, areas of activity, and capacities of the coalition known as the “Axis of Authoritarianism,” composed of Russia, North Korea, Iran, and China.

The analysis seeks to answer the following questions:

- How do the current cooperation structures and flexible sanction-evasion strategies of the “Axis of Authoritarianism” affect the West’s security and economic objectives?

- Why do such vastly different states — Putin’s Russia with its dream of restoring the Soviet empire, the Islamic theocracy of Iran, the communist superpower China, and the isolated socialist North Korea — choose to cooperate?

The Evil Axis

The greatest danger of accumulating enemies is that one day they might all become friends. In an era of geopolitical chaos, the boundaries between allies and enemies, friends and rivals, are increasingly blurred.

On January 2, 2024, when a missile struck the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv, it initially seemed like just another attack — but soon an oddity emerged: the missile fired by Russia did not appear to be of Russian origin (Reuters, 2024a).

This was only one of hundreds of missiles launched over five days during Russia’s most extensive airstrike campaign since the invasion began. When U.S. experts analyzed the missile photos, they found them nearly identical to North Korean models. North Korea had sent Russia 11,000 containers of weapons during the war (CSIS, September 2025a).

The arsenal used in the assault didn’t end there. Russia also employed Iranian-made drones and Chinese turbojet-powered cruise missiles. Their appearance on the Ukrainian battlefield was no coincidence — it was the result of overt, coordinated actions among Russia, Iran, North Korea, and China (GIGA, 2023).

The Biden administration began calling this alignment the “Axis,” a term that recalls both the Berlin–Rome–Tokyo Axis of World War II and former President George Bush’s famous phrase, the “Axis of Evil.”

China, Iran, Russia, and North Korea: Different Regimes, Shared Interests

The illusion formed in the post–Cold War period — that large-scale wars in Europe were a thing of the past and democracy’s advance was inevitable — has been completely shattered. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 marked the beginning of the end of that illusion. Although it took another decade for many to fully grasp the new geopolitical realities.

The harsh truth is that as a multipolar world takes shape, the resurgence of inter-bloc ideological confrontation necessitates bold and principled leadership in response to the “Axis of Authoritarian Powers” — actors with imperial ambitions who use military and hybrid aggression as primary tools to achieve their goals (Carnegie Endowment 2024b).

This changing reality calls for urgent and resolute investment in Europe’s defense and security. The continent’s military capacity has steadily eroded due to utopian visions such as a “unified continent from Lisbon to Vladivostok.” As a result, the Russian agenda presented by Vladimir Putin at the 2007 Munich Security Conference has been implemented step by step, culminating in NATO’s recognition of Russia as a strategic threat in 2022 (CSIS, September 2025b).

Slogans such as “limitless globalization” and “peace through trade” have utterly failed in the face of the emerging Axis of Authoritarianism (LLNL, February 2025b).

At the core of this axis stand Russia and China. Both have benefited for decades from access to Western technologies and the shift of manufacturing to the East. Long-sanctioned Iran and North Korea have joined them, capitalizing on Western policies that deprioritized security. The reconsolidation of authoritarian influence has become a magnet for illiberal regimes in the Global South, further diminishing the West’s reach and global influence (CSIS, September 2025c).

Years of weak Western responses to provocations — including the 2008 Georgia war and various hybrid attacks — emboldened Russia to launch its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Although China officially maintains a neutral stance, it plays a crucial role in sustaining Russia’s military-industrial complex. Between March and July 2023, Chinese companies shipped up to 10,000 CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines monthly to Russia (James Pomfret and Michael Martina, 2024). These shipments — along with semiconductors, navigation systems, and precision manufacturing equipment — allowed Russia to modernize its Soviet-era arsenal and develop new weapons systems (ODNI March 2025b). Beijing’s actions reflect a silent agreement with Moscow and complicate efforts to isolate Russia.

Simultaneously, Russia–North Korea cooperation has taken on a particularly dangerous nature. Both countries ratified a mutual defense treaty in late 2024 (The Guardian 2024b), creating a legal basis for direct military support from Pyongyang to Moscow.

According to South Korea’s Defense Minister Shin Won-sik, around 200 munitions factories were operating at full capacity in North Korea in 2024. The DPRK sent nearly 11,000 military containers to Russia via Rajin port, including artillery shells and “Bulsae-4” anti-tank guided missile systems, valued between $1.72 billion and $5.52 billion USD (Joe Saballa, 2024). North Korea is also expanding drone production, with Kim Jong Un asserting leadership ambitions in this technology. In exchange, Russia has strengthened North Korea’s air force by supplying MiG-29 and Su-27 fighter jets (defenseone.com, 2024).

Iran–Russia relations have transcended past tactical cooperation to become a comprehensive defense and economic alliance. A “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement,” covering defense and security cooperation, is expected to be signed soon. Based on the 2001 “Treaty on the Basis of Friendship and Cooperation,” this updated document will remain in force until 2026.

In parallel, negotiations continue on Iran’s cooperation within a full-fledged free-trade zone with the Eurasian Economic Union (ISW, 2024a).

Currently, Iran supplies Russia with Shahed drones, ammunition, and artillery, and has even opened a drone factory on Russian soil. In return, Moscow plans to provide Iran with advanced military technologies, including air defense upgrades (ODNI March 2025c). Their cooperation spans radar, electronics, and attack helicopters.

In 2023, Russia delivered two Yak-130 trainer aircraft to Iran. Iran also gained access to Western technologies via Western-made weapons captured in Ukraine. According to the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), Russia launched several satellites for Iran in 2022 and 2024 — including the “Khayyam” (Canopus-V), the high-resolution “Kowsar” imaging satellite, and “Hodhod” — and made additional commitments to space cooperation (ISW 2024b).

Although Russian specialists currently support Iran’s missile and space programs, Moscow has not yet transferred its most advanced systems, like the Su-35 or S-400, to Tehran. This delay likely stems from Moscow’s desire not to harm relations with Gulf states and its caution regarding Iran’s strengthening of regional proxy groups.

In addition, Iran–China, China–North Korea, and North Korea–Iran relations — despite certain goal differences — show that the axis is strategically consolidating (LLNL, February 2025d).

While deep trilateral or quadrilateral cooperation among them remains limited for now, the trend is clear: authoritarian powers are growing increasingly interconnected.

The West’s own vulnerabilities have deepened the crisis. According to the Independent Anti-Corruption Commission (NAKO) 2023 report, over 4,000 banned components from more than 200 companies across 22 Western countries were found in Russian weapons seized in Ukraine. In the same year, Russia imported €4 billion worth of technological components — 64 percent from U.S.-based companies (NAKO, 2024). These gaps allowed Russia to maintain and expand its military capabilities, seriously undermining the effectiveness of the EU’s 15 sanction packages.

Europe now faces a strategic dilemma. Eight NATO members — Canada, Italy, Belgium, Portugal, Spain, Croatia, Luxembourg, and Slovenia — still do not meet the defense spending threshold of 2 percent of GDP (eunevvs, 2024). In contrast, Poland allocated 4.1 percent in 2024, taking a leading position, followed by Estonia, Latvia, Greece, and the United States. The U.S. defense budget in 2024 was $755 billion, with around 9.9 percent allocated to research and new equipment. NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has called on member states to raise defense spending to 4 percent of GDP, increasing pressure in that direction (NATO 2025).

Global Ambitions of China, Iran, Russia, and North Korea

China, Iran, Russia, and North Korea differ greatly in terms of regime type. However, they also share many commonalities. Above all, each of them is driven by the ambition to expand its sphere of influence.

During the Soviet era, Russia controlled large parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Since Vladimir Putin came to power, Moscow has sought to destabilize some post-Soviet countries and to directly occupy others (ODNI, March 2025d).

The Islamic Republic of Iran has, since 1979, aimed to become the dominant power in the Middle East. Eliminating Israel from the map is also among Tehran’s declared ambitions (ISW, 2024c).

North Korea pursues a similar line. The Kim dynasty, which has ruled since the late 1940s, has heavily militarized the country and acquired a nuclear arsenal. This power is primarily used to threaten South Korea.

China, for its part, lays claim to Taiwan — a territory that has remained outside its control since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949. Following Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, the communist regime rapidly enriched the country and increased its military power. With nuclear weapons, advanced technologies, and a massive workforce, China has secured a strong position in the UN Security Council. In recent years, Beijing’s ambitions have expanded beyond Taiwan, aiming to bring all of Southeast Asia under its influence (Carnegie Endowment, September 2025).

The Main Common Factor: The United States

Another common feature uniting these four countries is that they are all adversaries of the United States. America opposes each of them and attempts to obstruct their plans. Washington has been arming its allies for many years and trying to curb the influence of these states (Nigel Gould-Davies, 2024).

Its most powerful weapon remains economic sanctions. The U.S., both directly and through its allies, seeks to exclude these countries from international trade. The consequences have included shortages of energy, technology, and even food. For instance, North Korea has suffered famine and economic collapse due to harsh sanctions related to its nuclear program. Iran was unable to sell its oil for many years and experienced serious financial crises. After the annexation of Crimea — and especially following the war in 2022 — severe economic restrictions were imposed on Russia as well.

The “Axis” – A New Alliance

These pressures brought the four countries closer together. In fact, trade relations had existed even earlier. For years, Iran had purchased missiles from North Korea in exchange for oil. China imported oil from Iran and conducted large-scale trade with North Korea. Russia cooperated individually with each of them. But the war in Ukraine elevated these relations to the level of an alliance (ODNI, March 2025e).

North Korea sends millions of shells and rockets to Russia, in exchange for food, energy, and technology (The Guardian 2024d).

Iran supports Russia with drones and missiles, and in return, plans to acquire modern fighter jets, helicopters, and S-400 air defense systems.

China buys record volumes of Russian oil, filling Moscow’s coffers, while transferring dual-use goods and military technologies. In exchange, it strengthens itself with Russian submarines and air defense systems (András Rácz and Alina Hrytsenko, June 2025).

Thus, everyone benefits. Despite sanctions, Russia’s survival is clear proof of this (Econstor 2023).

Russia, Iran, North Korea, and China — four countries with different ideologies — have transformed into a united front against sanctions and Western pressure. They meet each other’s needs, remain afloat through a “win–win” principle, and strive to expand their spheres of influence.

However, the goal is not just survival. This alliance increasingly harbors ambitions of becoming a new global power center.

The Struggle for a New World Order: The U.S. vs. the “Authoritarian Axis”

The ultimate objective of this alliance is to dismantle the current world order led by the United States. In fact, the primary reason for Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea coming together is the desire to establish an alternative, multipolar international order (Carnegie Endowment 2024e).

Their logic is simple: “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” The U.S. — with its powerful economy, devastating military force, global bases, and leadership of NATO — is too powerful to be defeated by any one of these states alone. That is why the four act collectively.

Looking at recent global events — from Armenia–Azerbaijan tensions to the endless wars in the Middle East — it becomes clear that most of these confrontations are rooted in this rivalry: on one side stands the U.S.-established order; on the other, the effort by Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea to build a new one (AP, May 2025).

This confrontation forces the U.S. to defend itself on multiple fronts simultaneously: against Russia in Ukraine, against China in Taiwan, against North Korea on the Korean Peninsula, and against Iran in the Middle East (mainly through Israel).

Putin, in particular, aims to shatter the “unipolar hegemony” of the United States that has persisted since the Cold War. The strategic goal is straightforward: to compel the U.S. to incur high defense costs in several regions at once. Ukraine, Taiwan, Israel, and South Korea are all links in this plan (Carnegie Endowment 2024f).

The First Signs of a New “Cold War”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine can be seen as the starting point of this plan. If the Kremlin achieves military and political success there, it will strengthen the global perception that the U.S. can be defeated — encouraging many currently hesitant countries to act more boldly.

The same strategy can also be observed in the Middle East. Hamas’s attack on Israel is considered the most serious blow to the Jewish state since 1973 (Arab Center Washington DC, 2023). Israel’s subsequent brutal military operations in Gaza and the West Bank caused thousands of civilian deaths and raised the risk of a much larger regional war.

Currently, Israel is fighting not only Hamas but also Hezbollah and armed groups in Syria. This puts the country of 9 million in a situation of massive financial and military strain. Israel’s ability to sustain this multi-front struggle is mainly thanks to U.S. military and financial support. However, the process also exhausts Washington, fragments its resources, and weakens the U.S.’s ability to project power globally.

BRICS and a Dollar-Free Economy

One of the strategies to weaken the U.S.'s global position is being carried out in the economic realm. The BRICS summit held in Kazan, Russia, is a clear example of this. Formerly consisting of five countries — Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa — the BRICS bloc doubled in size in 2024 with the inclusion of Egypt, Ethiopia, the UAE, and Iran (Anjali V. Bhatt, 2024).

Although the official theme of the summit was “multilateral cooperation for fair global development and security,” the most important decision was the proposal to create a joint currency independent of the U.S. dollar (Bloomberg, 2024). If this plan is implemented, the hegemonic role of the U.S. in the international financial system could be seriously undermined.

Turkey at a Crossroads

This global picture places Turkey in a difficult position. Turkey is both a NATO member and a country with deep economic ties to Russia, China, and Iran.

In 2023, trade between Turkey and the Russia–China bloc exceeded $70 billion (Can Sezer, Nevzat Devranoglu, and Dmitry Zhdannikov, 2024, Reuters 2024). But in the same year, Turkey’s trade turnover with the U.S. and Europe surpassed $300 billion (United States Trade Representative, 2023; Atlantic Council, September 2025). Thus, economically, Turkey depends on both sides.

Militarily, tensions with the United States remain unresolved: the S-400 purchase, expulsion from the F-35 program, and the ongoing F-16 issue. Nevertheless, Turkey is trying to buy “Eurofighter” jets from Germany while also developing its domestic defense industry.

Challenges of the New World Order

So far, the Authoritarian Axis has not generated a wind “strong enough to stand face-to-face with America.” It is still too early to claim that an alternative world order is being created. That’s because the state of external dependence I just described for Turkey also applies to the member states of this alliance.

For example, China must earn money in order to feed its massive population. But the revenues it can obtain from Russia, Iran, and North Korea are not enough to meet this need. China’s biggest customers are still the United States and Europe. Last year, China conducted $582 billion in trade with the U.S. (United States Trade Representative, 2024) and $786 billion with Europe. This figure is six times more than China’s combined trade with Iran, Russia, and North Korea (chinadailyhk, May 2025).

That means China would either have to reduce its population (and it is, to some extent, doing so), or somehow wrest Europe away from the United States and bring it to its own side — a very difficult task. Moreover, even though the leaders of the four countries regularly hold bilateral meetings, they have yet to come together as a group.

This raises a fundamental question: The current world order has the United States as its leader. But who would lead a new order? As the saying goes, “Two rams cannot share one pot.” And here we have four heads in a single pot:

- China — a one-party communist state that centralizes all power.

- North Korea — a socialist dictatorship built on self-isolation and self-reliance.

- Iran — an Islamic theocracy ruled by religious clerics.

- Russia — a highly centralized authoritarian system built around a single individual.

There are many contradictions between them. Yes, agreements are being signed, trade is happening, and arms are being bought and sold. But so far, they have only managed to keep the U.S. under pressure across different fronts. That is a success — but it’s not sufficient.

Because defeating the United States and its allied network is not something that can be achieved through military power alone. It is an extremely difficult undertaking. Furthermore, the U.S. possesses seemingly endless “cards.” Even the very platform on which you are reading this article is a product of America. The phone in your hand was either made in the U.S. or by its allies: even if it was assembled in China or elsewhere — the technology is still in Western hands (OECD/ICT statistics 2024).

Conclusion

This new geopolitical bloc — known as the “Axis of Evil” or the “Global Authoritarian Coalition” — composed of Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, has in the past decade taken shape not only as a temporary convergence of interests, but also as an ideological and strategic concept offering an alternative to the international order.

However, the deep structural differences within this coalition, economic dependencies, and leadership rivalries seriously call its long-term sustainability into question.

Although relations among these four states have deepened in recent years, they are still of a temporary character. These ties do not come close to the depth of the U.S.’s relations with its main allies, nor do they resemble the Soviet Union’s relationships with Warsaw Pact states — those countries were, in effect, satellites of Moscow.

True strategic cooperation would require more than bilateral contacts: it would necessitate joint mechanisms, regular military exercises ensuring unified command and control at both strategic and operational levels, mutual military interoperability, and joint strategic planning. Moreover, such cooperation typically involves a high degree of economic interdependence. But today, China’s level of economic interdependence with the West far exceeds its ties with Iran, Russia, and North Korea.

For the United States, the most effective way to prevent deeper cooperation among these four states is to weaken China’s relationships with the others. Without China’s support, Iran, North Korea, and Russia would remain weak and isolated from the rest of the world.

China’s role among these powers — as leader, organizer, and promoter of cooperation — is also critical, since alliances and coalitions often rely on strong leadership.

As tensions between these four countries and the West have grown in recent years, China has shown an increasing inclination to assume a leadership role. However, it remains unclear what China is willing to sacrifice in order to build deeper cooperation with economically weaker partners.

China is so deeply integrated into the global economy and political system that none of the other three countries can be compared to it. It benefits far more from the current world order than the other three, and its goals concerning international norms are different: China seeks to reform the system, while Russia, Iran, and North Korea aim to overturn it through revolutionary means.

Additionally, while Russia sees its relationship with European countries as openly hostile, China strives to preserve positive political and economic relations with them.

Therefore, the U.S. and its allies must find ways to reduce China’s interest in aligning with “rogue regimes” like Iran, Russia, and North Korea. Restoring the kind of positive relations that existed during the first two decades after the Cold War may no longer be possible, but fostering more constructive political and economic ties with the West could reduce Beijing’s interest in moving closer to the other three.

At the same time, to reduce the risk of exhaustion from facing multiple global crises or multi-front wars, the United States must enhance prioritization across regions, share burdens more effectively with allies, and enforce greater discipline in its commitments.

In the near future — especially as the war in Ukraine continues — the U.S. will not be able to fully sever China–Russia relations. But it can weaken them — for example, by leveraging Beijing’s interest in maintaining positive ties with Europe and by pursuing a balanced strategy toward China.

The White House must recognize that the more hostility Beijing feels from Washington, the more likely it is to increase support for Moscow.

Therefore, turning the cooperation of these four authoritarian states into the central framework of U.S. strategy would be dangerous — because there is significant uncertainty regarding how deeply this cooperation will evolve in the future.

At the same time, the future of U.S.–China relations is also uncertain. It is possible that Beijing has already “internally accepted” the prospect of confrontation with Washington. But its behavior so far suggests that it still values maintaining positive political and economic relations with the U.S. and Europe.

If America cannot find a model of coexistence that reduces tension and China’s threat perception, Beijing may decide to deepen its ties with the three U.S. rivals.

In that case, their cooperation will intensify, and the risks for the United States will increase. Washington and its allies would then be forced to adopt a “Cold War-style” strategy of military and economic containment against this authoritarian bloc — a strategy that would come at a very high cost for both the U.S. and its taxpayers, as well as for its allies.

References:

Carnegie Endowment 2024a. Cooperation Between China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia: Current and Potential Future Threats to America. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/10/cooperation-between-china-iran-north-korea-and-russia-current-and-potential-future-threats-to-america?lang=en

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, February 2025a. A New Axis? Bloc Rivalry and theFuture of Conflict. https://cgsr.llnl.gov/sites/cgsr/files/2025-03/Axis%20Workshop%20Summary_Feb%202025_Final.pdf

The Guardian, 2024a. Russia and North Korea Sign Mutual Defence Pact. https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/19/russia-and-north-korea-sign-mutual-defence-pact

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), March 2025a. Annual Threat Assessment. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2025-Unclassified-Report.pdf

Reuters, 2024a. “North Korea Likely Received Help from Russia on Submarines, South Korea Minister Says.” https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/north-korea-lauds-comradely-ties-with-russia-putin-meet-kims-foreign-minister-2024-01-16/

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) September, 2025a. Adversaries and the Future of Competition. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chapter-1-adversaries-and-future-competition

Carnegie Endowment 2024b. Cooperation Between China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia: Current and Potential Future Threats to America. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/10/cooperation-between-china-iran-north-korea-and-russia-current-and-potential-future-threats-to-america?lang=en

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) September, 2025b. Adversaries and the Future of Competition. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chapter-1-adversaries-and-future-competition

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) February, 2025b. Axis Workshop Summary: Bloc Rivalry and the Future of Conflict.

https://cgsr.llnl.gov/sites/cgsr/files/2025-03/Axis%20Workshop%20Summary_Feb%202025_Final.pdf

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) September, 2025c. Adversaries and the Future of Competition. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chapter-1-adversaries-and-future-competition

James Pomfret and Michael Martina, 2024. “China Sent CNC Tools and High-Precision Equipment to Russia Despite Sanctions.” https://www.reuters.com/technology/illicit-chip-flows-russia-seen-slowing-china-hong-kong-remain-transshipment-hubs-2024-07-21/

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) March 2025b. Annual Threat Assessment 2025. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2025-Unclassified-Report.pdf

The Guardian, 2024b. “Russia and North Korea Sign Mutual Defence Pact.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/19/russia-and-north-korea-sign-mutual-defence-pact

Joe Saballa, 2024. Ukraine Says Destroyed N. Korean Bulsae-4 Missile Used by Russia

https://thedefensepost.com/2024/12/03/ukraine-destroyed-bulsae-missile/?utm

defenseone.com, 2024. Russia in talks to send fighter jets to North Korea, INDOPACOM says https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2024/12/russia-talks-send-fighter-jets-north-korea-indopacom-says/401520/?utm

Institute for the Study of War (ISW) 2024a. Iran–Russia Military Cooperation Expands Amid Ukraine Conflict. https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-july-8-2024/

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) March 2025c. Annual Threat Assessment 2025. https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2025-Unclassified-Report.pdf

İnstitute for the Study of War (ISW) 2024b. Iran–Russia Military Cooperation Expands Amid Ukraine Conflict. https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-july-8-2024/

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) February, 2025d. Axis Workshop Summary: Bloc Rivalry and the Future of Conflict.

https://cgsr.llnl.gov/sites/cgsr/files/2025-03/Axis%20Workshop%20Summary_Feb%202025_Final.pdf

NAKO (Independent Anti-Corruption Commission) 2024. Western Components in Russian Weapons: https://nako.org.ua/en/research/u-pivnicnokoreiskii-raketi-yaku-zbili-v-ukrayini-je-neshhodavno-virobleni-komponenti-zaxidnix-kompanii

Eunevvs, 2024. Italy is among 8 NATO countries that have not yet reached the 2 percent defense spending threshold. https://www.eunews.it/en/2024/06/18/italy-is-among-8-nato-countries-that-have-not-yet-reached-the-2-percent-defense-spending-threshold/

NATO, 2025. Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2024–2025). Brussels: NATO Public Diplomacy Division. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/events_238150.htm

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) March 2025d. Annual Threat Assessment 2025.

https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2025-Unclassified-Report.pdf

İnstitute for the Study of War (ISW) 2024c. Iran–Russia Military Cooperation Expands Amid Ukraine Conflict. https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/iran-update-july-8-2024/

Reuters, 2024a. “North Korea Likely Received Help from Russia on Submarines, South Korea Minister Says.” https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/north-korea-lauds-comradely-ties-with-russia-putin-meet-kims-foreign-minister-2024-01-16/

The Guardian, 2024c. “Russia and North Korea Sign Mutual Defence Pact.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/article/2024/jun/19/russia-and-north-korea-sign-mutual-defence-pact