(This analysis is prepared within the broader study of post-Soviet authoritarianism)

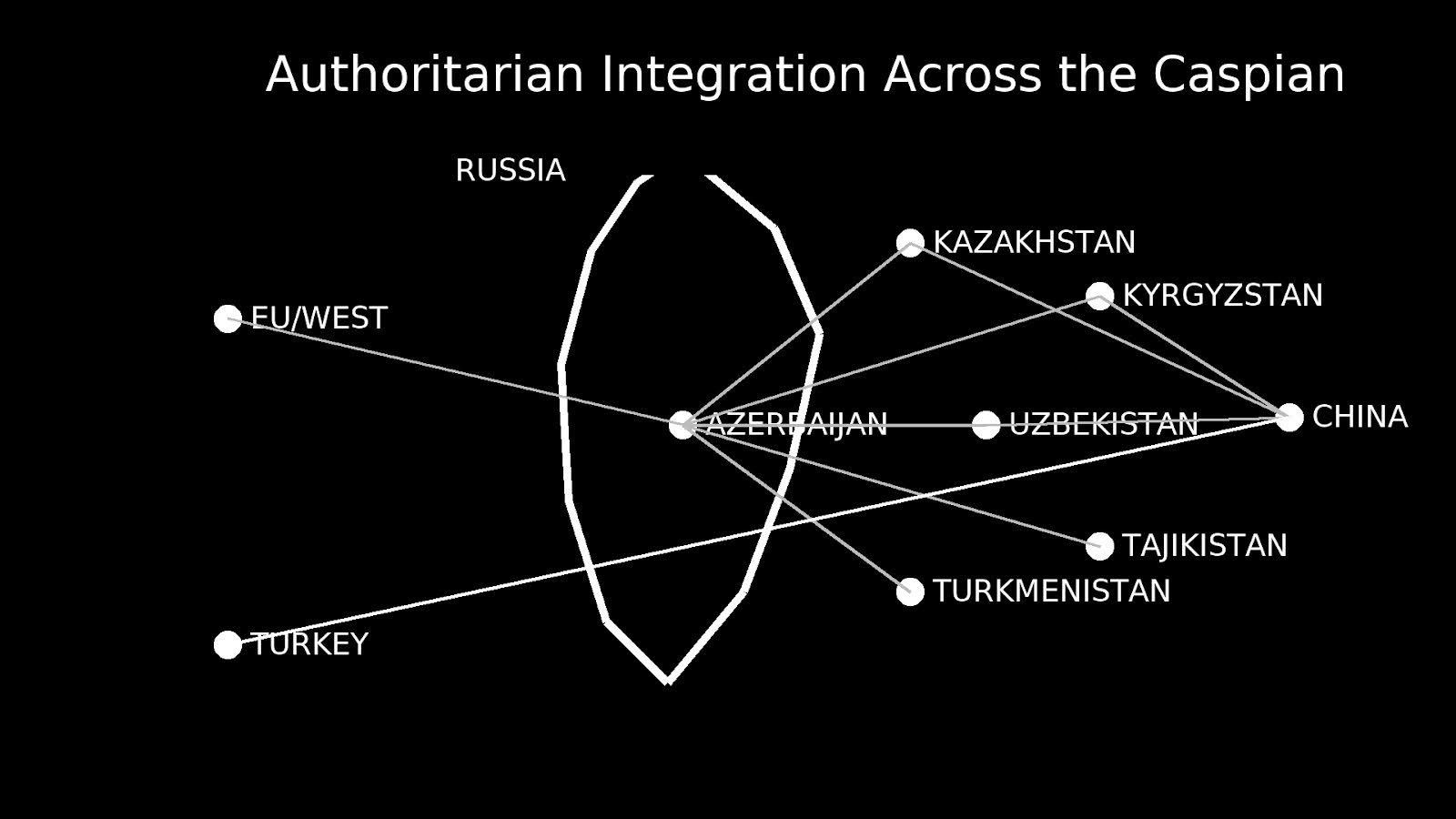

Azerbaijan’s accession as a full-fledged member to the Central Asian Consultative Meetings is part of the large-scale structural changes that have unfolded in this region in recent years. This step creates a new geopolitical link between the South Caucasus and Central Asia, uniting these two geographies (Euronews, Nov 2025). Although the visible part of the discussions focuses on economic and transport projects, in such regional groupings the alignment of authoritarian governance models, the sharing of legitimacy mechanisms, and attempts by regimes to ensure one another’s security constitute a much more important priority (Christina Cottiero, Stephan Haggard, 2022).

Over the past five years, the political situation in the South Caucasus and Central Asia has evolved rapidly. The decline of Russia’s influence has disrupted the long-standing Moscow-centric order in the post-Soviet region, creating new opportunities. Among the main actors filling this vacuum are China and Turkey. China’s expanding soft power and its emphasis on the stability of authoritarian regimes open up new avenues for post-Soviet authoritarianism (Oleg Antonov & Olena Podolian, 2023). Turkey’s ideological and military-political influence significantly shapes security issues in Central Asia and the South Caucasus, while also playing an increasingly important role in strengthening authoritarian governance methods.

On the other hand, since the 2020 war, Ilham Aliyev has sought a new role in the regional balance of power. Official Baku is attempting to shape the post-conflict architecture according to its political and security priorities (Trend, Oct 2025). This indicates that the emerging informal authoritarian alliances in the region will continue to grow stronger.

According to the thesis of this article, the new principles of cooperation developing between Central Asian countries and Azerbaijan rest on four main objectives:

1. Sharing experiences in authoritarian governance models.

This includes the exchange of practices such as electoral fraud, repression techniques, and the “artificial weakening of the opposition.”

2. Regime security.

Demonstrating collective resistance against the democratic demands of the West and forming platforms that support one another in order to reduce international pressure.

3. Formation of an alternative geopolitical center.

The decline of Russian power and limited Western influence encourage regional states to create their own “authoritarian council.”

4. A multipolar authoritarian dynamic evolving between Turkey and China.

Ankara provides security, while Beijing provides economic support.

In this article, KHAR Center will systematically examine the ideological, political, economic, and security dimensions of this process and attempt to determine the significance of Azerbaijan’s role in the new regional structure.

The Phenomenon of Authoritarian Convergence

In political science, the term “authoritarian convergence” refers to the growing cooperation among authoritarian regimes over time. It is an important analytical concept that explains how governance methods, legitimacy narratives, and security architectures come to align simultaneously (Francesco Cavatorta, 2010). This concept relates to the process by which authoritarian systems learn from one another, legitimize themselves, and work together to neutralize democratic pressures.

Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way study this phenomenon within the context of “authoritarian learning,” arguing that regimes in the post-Soviet region do not harden in isolation. They draw inspiration from regional practices, share models of repression and co-optation, and offer each other political support (Steven Levitsky, Lucan A. Way, 2005).

Henry Hale explains the process in a more systemic way, noting that patronal networks expand not only within a single country but also on a trans-regional scale. As a result, informal avenues of cooperation emerge between authoritarian regimes (Henry E. Hale, 2014).

From this theoretical framework, the parallels observed between Central Asia and Azerbaijan are not accidental. All regimes in the region share the personalist leadership model. In this model, power is concentrated around a family, a leader, or a narrow political elite. Governance becomes personalized, and the political system becomes tied to the physical presence and political lifespan of the leader. At the same time, an image of economic and technological modernization is created, but political institutions, the judiciary, and democratic oversight mechanisms are deliberately kept weak.

Economic co-optation becomes the main tool of governance—rent revenues are distributed among the elite, and economic privileges are based on political loyalty. Total control over the media, state monopoly in the information sphere, self-censorship, and the criminalization of alternative views are widely practiced. Legitimacy narratives such as “stability,” “development,” and “national progress” are systematically constructed. In this way, society is distanced from politics through the production of threats, chaos imagery, and enemy narratives.

Azerbaijan and Central Asian countries use similar political templates. These regimes present security as the main pillar of legitimacy, fuse modernization with authoritarianism, routinely emphasize stability, and work to expand their spheres of influence. They also describe the West’s democracy demands as “foreign interference” (Elman Fattah, Nov 2025).

For this reason, “authoritarian convergence” is a practical description of the increasing political, informational, and security collaboration between Central Asia and Azerbaijan over the past decade. Azerbaijan’s participation in the Consultative Meetings indicates that this coordination has entered the stage of institutionalization.

Azerbaijan’s Choice: Why the Central Asian Bloc?

The Russia–Ukraine conflict has created a “geopolitical vacuum” in the post-Soviet space due to the weakening of the Kremlin. Moscow’s declining military-political influence in the South Caucasus and Central Asia pushes countries in the region to reconfigure their security and legitimacy principles. Baku views this situation as an opportunity to create strategic balance and has chosen to actively participate in new regional coalitions (Ruslan Zaporozhchenko, 2024).

Over the past five years, the Ankara–Baku alliance has strengthened even further and now extends its influence into Central Asia. With Turkey’s military and technological support, Azerbaijan seeks to build an alternative power center in the region and develop its energy diplomacy (AzeMedia, 2024). If relations with the West once again become conflictual, Central Asia will serve as an additional field of legitimacy for Baku. In terms of political models, ideological approaches, and security concepts, the situation in Central Asian countries aligns fully with Azerbaijan’s governance principles.

Meanwhile, the failure of the traditional international security system creates opportunities for China to strengthen its presence in Central Asia, just as it elevates Turkey to a more dominant position in both the Caucasus and Central Asia.

Under these new geopolitical conditions, Azerbaijan gains the opportunity to integrate with Central Asia while simultaneously moving closer to China as an alternative major power center.

Motivations of Authoritarian Governance

A significant yet less discussed dimension of the relationship between Azerbaijan and Central Asia is the compatibility of their authoritarian governance models and the associated process of mutual learning. The exchange of authoritarian practices is already taking place between regional countries. Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan’s “smart surveillance” systems and social media monitoring strategies—core components of digital authoritarianism—are now widely applied in Azerbaijan as part of regional cooperation (Ildar Daminov, 2024).

Azerbaijan’s Specific Role

Despite certain similarities, Azerbaijan’s position within the regional authoritarian alignment has several distinctive characteristics: energy diplomacy and unique advantages in relations with the West.

Many Central Asian countries hold less importance for the West, but Azerbaijan has risen to a strategically significant position for Europe’s energy security amid the Russia-West confrontation. Baku is one of the key alternative transit routes for gas transport and is the strategic hub of the Southern Gas Corridor. It is also critical for the West in terms of energy diversification (Yana Zabanova, 2024).

This situation grants Baku substantial diplomatic maneuvering capacity: it both strengthens authoritarian integration with Central Asia and maintains minimal relations with the West to evade strategic pressure.

Thus, Azerbaijan’s relations with the West resemble an energy-centered alliance. This is a special geopolitical advantage that none of the Central Asian capitals possesses.

Forecast for 2030: the deepening of authoritarian regionalism

If current trends continue, by 2030, the following picture will emerge: the Central Asia–Azerbaijan–Turkey axis will become a regional hub of authoritarian governance. Azerbaijan’s political system will evolve toward geopolitical isolation and a heightened security model; at the same time, relations with Europe—while still centered on energy—will shift toward a norm of politically cold cooperation.

The outlook toward 2030 once again demonstrates that Azerbaijan’s authoritarian alliance with Central Asia will further harden the dynastic governance models of the regimes on both sides of the Caspian.

Thus, Azerbaijan’s accession as a full-fledged member to the Central Asian Consultative Meetings constitutes part of the intensifying authoritarian convergence observed in the post-Soviet region over the past five years. This process encompasses the synchronization of political governance methods, legitimacy strategies, and security approaches among the regimes. This integration presents Azerbaijan with three strategic outcomes:

First, the coordination of authoritarian governance standards across the region. Through cooperation with Central Asia, this strengthens Baku’s domestic political model.

Second, it formalizes the exchange of authoritarian practices.

Third, it indicates that the regime’s security-centered governance method will rise even further.

Despite the short-term calm provided by energy diplomacy, relations between Azerbaijan and the West are weakening at the level of values, increasing the risk of political isolation. This will strengthen Azerbaijan’s full integration into regional authoritarian platforms and accelerate the convergence of authoritarian systems in the South Caucasus and Central Asia.

References:

Euronews, Nov 2025. Central Asian leaders welcome Azerbaijan as new member at historic summit. https://www.euronews.com/2025/11/16/central-asian-leaders-deepen-regional-integration-as-azerbaijan-joins-consultative-format

Christina Cottiero, Stephan Haggard, 2022. Stabilizing Authoritarian Rule: The Roleof International Organizations. https://ucigcc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Cotierro-and-Haggard-Working-Paper-7.28.22.pdf

Oleg Antonov & Olena Podolian, 2023. Coopting post-Soviet youth: Russia, China, and transnational authoritarianism. https://balticworlds.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/BW_2023_3_Introduction.pdf

Trend, Okt 2025. President Ilham Aliyev heading Azerbaijan's shift into regional political hub. https://www.trend.az/azerbaijan/politics/4105139.html

Francesco Cavatorta, 2010. The Convergence of Governance: Upgrading Authoritarianism in the Arab World and Downgrading Democracy Elsewhere? https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/19436149.2010.514472

Steven Levitsky, Lucan A. Way, 2005. Ties That Bind? Leverage, Linkage, and Democratization in the Post-Cold War World. https://academic.oup.com/isr/article-abstract/7/3/519/1848812

Henry E. Hale, 2014. The Emergence of Networks and Constitutions. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/patronal-politics/emergence-of-networks-and-constitutions/F0AF150475DE86364DE7DCD2B8EA08FA#access-block

Elman Fattah, Nov 2025. The Stability and Legitimacy Mechanism of Azerbaijani Authoritarianism. https://kharcenter.com/en/publications/the-stability-and-legitimacy-mechanism-of-azerbaijani-authoritarianism

Ruslan Zaporozhchenko, 2024. The End of Russian Hegemony in the Post-Soviet Space? War in Ukraine and Disintegration Processes in Eurasia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/379599749_The_End_of_Russian_Hegemony_in_the_Post-Soviet_Space_War_in_Ukraine_and_Disintegration_Processes_in_Eurasia

AzeMedia, 2024. Türkiye-Azerbaijan relations: The building of an alliance. https://aze.media/turkiye-azerbaijan-relations-the-building-of-an-alliance/

Ildar Daminov, 2024. When Do Authoritarian Regimes Use Digital Technologies for Covert Repression? A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Politico-Economic Conditions. https://openresearch.ceu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/13d11890-541e-4538-adf6-bdfbe83bcfdf/content

Yana Zabanova, 2024. The EU and Azerbaijan as Energy Partners: Short-Term Benefits, Uncertain Future. https://energytransition.org/2024/11/the-eu-and-azerbaijan-as-energy-partners-short-term-benefits-uncertain-future/